- Informationen

- KI Chat

Law paper 2 revision

Law

Empfohlen für dich

Kommentare

Was Studierende auch interessant finden

Text Vorschau

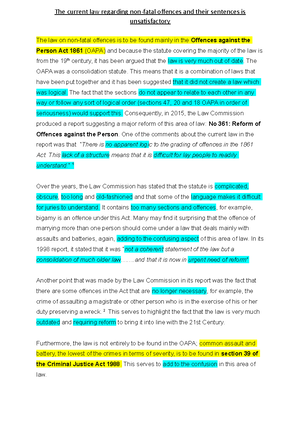

Paper 2 Law

Section A

Parliamentary law making

Process:

consultation phase (green paper is issued by the government containing policy proposals for debate, allowing people inside and outside of Parliament to give the department feedback. White paper is drafted, often by a government department or minister, and formally introduces the bill to Parliament )

First reading (title of bill is read to prepare Parliament for debates, a verbal debate takes place. A majority allows the bill to pass to the next stage)

Second reading (main policy areas are debated followed by a vote)

Committee stage (standing committee of 16-50 MPs conduct a line by line examination of the bill, MPs usually chosen based on expertise. Language is refined, a vote is taken on every amendment proposal.)

Report stage (standing committee reports back to the house, to make sure the second meeting principles were kept to. More amendments can take place but will need a further vote)

Third reading (review of whole bill. Often a formality)

Goes through both houses, if an amendment is made in the second house the first house must have another vote and agree. If this happens several times its called Parliamentary ping- pong. When both houses agree it goes for Royal Assent.

Different types of bills

Public bills: presented by members of the government, applies to general population.

Private members bills: introduced by MPs or Lords, applies to general population. Can be introduced by ballot (get priority in the limited time on Parliamentary agenda, held on second sitting Thursday of a Parliamentary session), ten minute rule (Members make speeches of no more than ten minutes outlining their position, which another Member may oppose in a similar short statement. It is a good opportunity to raise the profile of an issue and to see whether it has support among other Members.), or presentation (Any Member may introduce a bill in this way as long as he or she has previously given notice of their intention to do so. Members formally introduce the title of the bill but do not speak in support of it - they rarely become law.)

Private bills: Private bills are usually promoted by organisations, like local authorities or private companies, to give themselves powers beyond, or in conflict with, the general law. Private bills only change the law as it applies to specific individuals or organisations, rather than the general public. Groups or individuals potentially affected by these changes can petition Parliament against the proposed bill and present their objections to committees of MPs and Lords.

Evaluation:

When a bill reaches the House of Lords, First and Second Reading are no different in essence to their counterparts in the House of Commons. However, when the bill reaches the Committee Stage, there are some key differences to note. Firstly, in the House of Lords, the whole house conducts the Committee Stage - there are no standing committees in the House of Lords. Secondly, although the House of Lords has the authority to delay a bill, they only have limited power to do so, due to the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949. A delay to money bills can only be up to one month and to all other bills up to one year. After that, the House of Commons can bypass the House of

Lords and take the bill straight to Royal Assent. The House of Commons is seen as superior in this regard, due to the fact that their members are democratically elected. First reading allows debates to be prepared, but can be seen as a time wasting stage. Royal assent not denied since 1707 when Queen Anne refused to give royal assent to Scottish Militia Bill.

Statutory interpretation

Literal rule: the law is read and followed in its most literal sense. (Cheeseman v DPP, charged with ‘exposing himself to the annoyance of passengers’. Police that caught him were stationed in the bathroom, so they weren’t passengers. Found not guilty). Advantages – no scope for judges prejudices to interfere, respects parliamentary sovereignty and separation of powers, encourages precise drafting. Disadvantages – produces absurdities, ignores the fact language evolves, demands unattainable perfection from Parliamentary draftsman.

Golden rule: usually used if literal rule produces absurd results. This means a secondary meaning of the same words can be used. When the narrow approach is applied when the word or phrase is capable of more than one literal meaning and the narrow approach is applied this allows the judge to apply the meaning that avoids the absurdity, like how season can mean spring summer winter autumn or it can mean salt and pepper. Under the broad approach, the court will modify the meaning to avoid the absurdity so in the narrow approach, the judge chooses the meaning that avoids the absurdity in the broad approach they narrow the one literal meaning to avoid the absurdity examples are given in the cases below. (R v Allen, D charged with bigamy, the Golden Rule the court applied that the word marry should be interpreted as to go through a marriage ceremony, therefore, it didn't matter whether or not you were married i. you had a wife or a husband what mattered in this sense is that Marry had its other meaning about going through a marriage ceremony and Allan's conviction was upheld. Advantages – stops absurdities, puts Parliaments intentions into force, still respects parliamentary sovereignty. Disadvantages – subjective, can give judges too much power, inconsistent as its not clear when it should be used.

Mischief rule: This principle is used by the courts to determine the intention of the legislators. This principle aims at finding out the mischief and defect in a statute and to implement a remedy for the same. This principle was first applied in an English case in the early 16th century. For example, ‘no dogs allowed’ doesn’t necessarily include guide dogs. Laid down in Heydon’s case. Advantages – helps avoid absurdities, promotes the original purpose of act, fills the gaps in the law. Disadvantages – if the act is old its hard to find original purpose, uncertain how law will be applied.

Purposive approach: used in European court of justice. Thus the purposive approach to statutory interpretation seeks to look for the purpose of the legislation before interpreting the words. It has often been said that the purposive approach is a mixture of the domestic rules, however, whereas the domestic rules require the courts to apply the literal rule first to look at the wording of the Act, the purposive approach starts with the mischief rule in seeking the purpose or intention of Parliament. They also use extrinsic aids, for example the Hansard being used in Pepper v Hart. Advantages -

Parliamentary Sovereignty and EU law: EU law used to have sovereignty over UK law, which was one of the reasons to leave the EU. EU law was often wrote into British law in order to combat this, such as the European Convention of Human Rights being encompassed into the Human Rights Act. Advantages – flexible, allows judges to cope with unforeseen situations, aids like Hansards make it easier to find out Parliaments intentions. Disadvantages – judges given too much power going against separation of powers (Montesquieu), ignores divisions in Parliament between parties.

past decisions. Usually courts are even bound by their own decisions, but the Court of Appeal and the UK Supreme Court have specific ways of getting around this issue, in very limited circumstances. In the case of Young v Bristol Aeroplane, the Court of Appeal decided that it need not be bound by its own previous decisions, if at least one of the following criteria could be met: The court is entitled and bound to decide which of two conflicting decisions of its own it will follow The court is bound to refuse to follow a decision on its own which, though not expressly overruled, cannot, in its opinion, stand with a decision of the House of Lords (now the UK Supreme Court)The court is not bound to follow a decision of its own if it is satisfied that the decision was given per incuriam. Finally, the UK Supreme Court is able to depart from precedent using a different mechanism, the Practice Statement 1966. This was a document created by Lord Gardiner LC, who argued that although the UK Supreme Court (then the House of Lords) should aim to follow their own past decisions, they should be able to depart from them, “when it appears right to do so”.

Evaluation

Advantages: Flexibility: – Precedents can be avoided in many ways and this enables the system to adapt to new situations, to meet the needs of a changing society, certainty: – judicial precedents provides certainty of the outcome of a case, making it possible to forecast what a decision will be and plan accordingly by looking at existing procedures, detailed practical rules: – judicial precedent is set by real cases as oppose to statutes which are more theoretical and logical. These cases show in detail the application of the law enabling judges to make an accurate informed decision on a case, uniformity in the law: – similar cases will be treated in the same way. This is important to give the system a sense of justice and make the system acceptable to the public.

Disadvantages: Ridgity: – judicial precedents forces judges to stand by a previous decision, this encourages bad judicial decisions to perpetuate for a long time before a successful appeal is heard to overrule setting a new precedent, uncertainty & Complexity; – the advantage of certainty can be lost if there are more than one judges sitting on a case forming more than one ratio decidendi. This makes it difficult and more complex to determine which ratio will bind future case of similar nature, volume & timelines: – it takes a long time for cases to be decided upon as judges have to find the ratio of a case which may be buried in a large volume of law reports from existing cases, degradation of lower courts: – the overruling of a lower court’s decision by a higher court on an appealed case weakens and lowers the respect of that lower court.

Tort Law

Negligence

The civil liability is based on establishing three principles: duty of care, breach and damage. Once these principle have been established, compensation may be paid out to a claimant, which aims to put them back into the position they were in before the damage occurred. Established in Blythe v Birmingham waterworks – act or omission that causes injury or damage. Donoghue v Stevenson established neighbour principle.

Caparo – reasonable foreseeability: Topp v London bus (left bus with keys in, someone stole it and killed someone. Wasn’t foreseeable). Kent v Griffiths (ambulance took too long, foreseeable).

Caparo - proximity: established in Bourhill v Young (claimant heard motorcycle collision, walked past site of crash after. Went into shock and baby was stillborn. Not proximate as claimant didn’t know the dead person). Can be in space, time etc.

Caparo – fair just and reasonable: Hill v CCWYP (claimant sued police for daughters death as police potentially knew the Yorkshire ripper, but lacked evidence. Not FJR). Usually a policy part, subjective and case to case basis.

Robinson v CCWYP: for non-novel cases. (Nettleship v Weston for drivers, Bolam for doctors etc)

Breach of duty: Blythe (objective test to reasonable person), Glasgow Corp v Muir (teachers spilt tea on children. Reasonable knowledge/skill). Bolam – body of medical professionals, Bolitho – logical and defensible (proof they did what made sense). Learners – compared to professional (Nettleship v Weston), children -compared to same age (Mullins v Richard)

Remoteness/causation: risk factors, special characteristics (Paris v Stepney), size of risk (Bolton v stone), precautions (Latimer v AEC), Risk known (Roe v MOH), Public benefit (Watt v Hertfordshire. Factual causation – but for test (Barnett). Intervening act (Knightley v Johns for 3 rd party). Wagon mound (remoteness), thin skull rule (Smith v leech brain)

Evaluation:

Advantages :

DoC – Robinson saves judges time and uses precedent principles to keep consistency with non-novel situations but is very recent. Caparo is consistent and easier to follow than neighbour principle with less legal terms, also flexible for policy decisions etc. FJR allows for common sense of judges. Utilitarianism (Bentham – doing what benefits the most people, Hill v CCWYP)

Breach – reasonable man is flexible. Bolam has opinion from professionals rather than judges as they have expertise. Bolitho limited self-regulation from Bolam. Fair on claimant to try learners same as professionals in order to get justice for damages, and should have insurance.

Risk factors – for public benefit (social paternalism). Drives up standards (Latimer, sawdust on factory floor). Size of risk has common sense approach (Bolton v Stone).

Thin skull rule – promotes safety standards, cant not give people with pre-existing conditions.

Disadvantages:

DoC – Caparo is complex and longer than neighbour principle, inconsistent with foreseeability and FJR. No real definition of proximity in the Caparo test, leading to inconsistency and

‘occupier’ does not have to actually occupy (as in ‘live at’) premises in order to come under the Act. S(3)(a) of the Act notes that premises is not just land and buildings which might be considered premises, but vessels, vehicles and aircraft, including temporary structures (Wheeler v Copas - scaffolding).

Express permission is the occupier expressly inviting those on the premises (can be written or vocal) and deviation will make them a trespasser.

Implied permission lacks express permission but is assumed to be objectionable to the occupier, like delivery person with delivering mail or customers with shops. These have natural limitations, like not walking into the house with the mail (Lowery v Walker).

Lawful right of entry (s(6)) includes police officers, fire fighters etc. other acts can cover this (Police and Criminal Evidence Act).

Those who enter property in accordance with a valid contract are held to be a lawful visitor under the act, and notably, if the relevant contract provides for a higher standard of care it will apply. So if a landowner hires builders, and agrees to being held strictly liable for any accidents that occur, then that duty of care will apply (in addition to the lesser one contained in the 1957 Act).

The relevant duty of care can be found in s(2) of OLA 1957. An occupier must “take such care as in all the circumstances of the case is reasonable to see that the visitor will be reasonably safe in using the premises for the purposes for which he is invited or permitted by the occupier to be there.” A distinction should also be noted that the duty is based around preventing injury in visitors, rather than ensuring that premises are objectively safe. Thus, whilst a deep pit presents an objective hazard, the occupiers duty is based on ensuring nobody is injured by it (for example, by putting up warning signs or fencing it off.)

s(3)(a) warns that children can be expected to be less careful than adults, and, by implication, that a greater level of care might be required to keep them from harm. The common law has sought to strike a balance between the responsibilities of parents and occupiers to prevent harm from befalling children (Phipps v Rochester). Occupiers must protect children from allurements (Glasgow Corp v Taylor). Older children are less susceptible to harm than younger children. Thus, the relevant level of care will depend on the nature of the risk and the age and awareness of the child involved.

At the opposite end of the spectrum lie skilled visitors, as noted in s(3)(b). Occupiers can assume that such visitors will have a greater awareness of risks and the relevant precautions that they should take - although importantly, this increased competence will only apply to risks whose nature matches the skill of the visitor. So an electrician will be owed a lesser duty of care by an occupier - but only in relation to risks of electric shock and similar. (General Cleaning v Christmas). Just because a risk is of a nature which might be encountered by a skilled visitor, that does not dispel the entirety of the occupier’s duty of care - an occupier must still act reasonably.

As per s(4)(a), warnings only fulfil the occupier’s duty of care if they enable a visitor to be reasonably safe. s(4)(b) provides a list of the situations in which an occupier will be held liable for a harm caused by an independent contractor. Firstly, where in was unreasonable to entrust the work to an independent contractor in the first place. This is to prevent an occupier from hiring independent contractors to deal with all aspects of their premises in order to avoid liability. Secondly, where the occupier failed to take reasonable steps to ensure the independent contractor was competent - for example, a landlord who hires an independent engineer to do gas safety checks will be expected to check that he is qualified. Thirdly, where the occupier has failed to take reasonable steps to check the work of an independent contractor. So if a school hires an independent contractor to clear ice off of steps, they will be expected to check that it has been done.

There are three commonly encountered defences when dealing with OLA 1957. The first is the defence of consent, as per s(5). Visitors will often be in situations in which they are aware of a risk, but choose to continue anyway - so a visitor who is aware of a wild horse, but decides to continue into its field regardless, may well be held to have consented to the risk. Secondly, there will often be scenarios in which a visitor has acted poorly around a risk, and thus the defence of contributory negligence can be raised. So visitors who fool around near a cliff edge

and fall off will likely be held to have contributed to their injuries. Thirdly, exclusion clauses (a matter of contract law) will often be employed by occupiers as a means to avoid liability.

OLA 1984

This provides the basis for the duty that an occupier has towards those who are not lawful visitors. This includes trespassers - those who lack permission in the first place, as well as those who have overstepped the bounds of their permission. OLA 1984 also covers those who lawfully exercise a private right of way (this is a property law concept), and those who have their access covered by right to roam legislation. Trespasser is described as “someone who goes on the land without invitation of any sort and whose presence is either unknown to the proprietor or, if known, is practically objected to.”

S(3) describes three criteria for a duty of care to exist. Firstly, the occupier must be aware of the hazard, or have reasonable grounds to believe it exists. Notably, this is a subjective standard - so whether this condition is met will depend on an occupier’s actual knowledge of either a hazard or the symptoms of a hazard. Secondly, the occupier must know or have reasonable grounds to believe that a trespasser is in the vicinity of that danger. Again, this is also a subjective standard, based on the occupier’s knowledge. The ‘reasonable grounds’ element is important here - an occupier does not need to be looking out their window at the time a trespasser is injured by a hazard. Instead, this condition is more about an occupier being aware of the phenomenon of trespassers on their land. Examples of such grounds include an occupier’s knowledge that people often use their field as a shortcut, or that children often use a broken fence as a way to access a building site managed by the occupier. Thirdly, the relevant risk must be one which the occupier would reasonably be expected to protect against. This is not subjective, but objective - the courts will ask what the reasonable occupier would have done. This will depend a lot on the nature of the risk - a hidden and serious risk will require greater action than an obvious and mild one - contrast a minefield with some nettles. We’d expect a reasonable occupier to go to great lengths to protect trespassers from the former, but not the latter. The application of the duty of care can be seen in Young v Kent.

As with OLA 1957, greater lengths will be needed to protect children than adults - so pay special attention when it is known that children are trespassing. Nevertheless, the courts will rarely shy away from acknowledging the fact that there comes a point at which children should be aware of a risk they are taking as seen in Keown v Coventry.

Vicarious Liability

Vicarious liability can be established where a duty of care imposed on an employer has been broken, but the claimant cannot identify which employee breached it. An employer, then, will not escape liability where a particular employee of his cannot be identified to have been

can operate harshly and absolve a defendant of liability no matter how much at fault they may be.

Volenti non fit injura – is a common law doctrine which states that if someone willingly places themselves in a position where harm might result, knowing that some degree of harm might result, they are not able to bring a claim against the other party in tort.

Compensatory damages – A sum of money awarded in a civil action by a court to indemnify a person for the particular loss, detriment, or injury suffered as a result of the unlawful conduct of another.

Mitigation of loss – Mitigation of loss is an area of law which operates to limit the amount of damages that can be recovered for breach of contract or commission of a tort. When a person suffers a legal wrong, they are not entitled to sit back, let damage accrue and then recover all the damage in money from the defendant.

Injunctions - Injunctions can provide a remedy in some tort claims and are most commonly used in the torts of nuisance and trespass. An injunction is an order of the court prohibiting a person from doing something or requiring a person to do something. It is an equitable remedy.

Law paper 2 revision

Fach: Law