- Information

- AI Chat

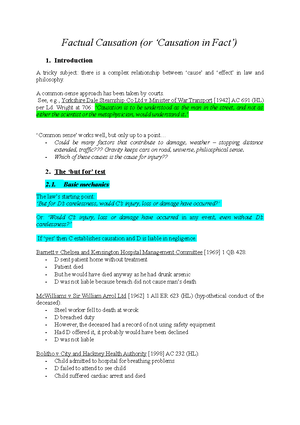

Occupiers Liability Handout

Law of Tort (LAW209)

University of Liverpool

Recommended for you

Preview text

Occupiers’ Liability Occupiers’ liability is a particular application of the tort of negligence. Defendant occupiers can be held liable for injury to the person, or to property, caused by their failure to take reasonable care. Who owes a duty of care to someone who occupies a premises? Claimants bring claims where the defendant did not take reasonable care for the state of the premises, but defendants argue that the claimant chose to take a risk. Geary v Weatherspoon’s- Ms Geary went to Weatherspoon’s, drank a few drinks and decided to slide down a bannister, she fell and suffered injuries. She argued Weatherspoon’s ought to have contemplated that might have happened, should have put a warning. They argued that her injury was a result of what she chose to do not the state of the premises. Note that many of the modern cases appear influenced by a desire to protect occupiers from excessive liability/perceived ‘compensation culture.’ Common law (pre-1957) Liability was governed by the label courts used to describe the entrant. The old common law’s distinctions between different categories of entrant caused confusion and inconsistency. The categories of entrant were: i) contractual entrants; ii) invitees; iii) licensees; and iv) trespassers. This area was just dealt with at common law. Liability was dependant on how the claimant was labelled, there were 4 different labels for the different entrants. But a problem arose because the courts have created 4 different standards of care, the rules became overcomplicated, and were inconsistently applied. The common law was largely replaced by a statutory regime of occupiers’ liability comprising two statutes: the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957 (which deals with liability to visitors) 1; and the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984 (dealing with liability towards non-visitors). Liability to visitors: Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957 S(1) – ‘An occupier of premises owes the same duty, the common duty of care to all his visitors.’ Establishing an occupier’s liability under the 1957 Act therefore requires consideration of the following issues: Who is/are the occupier(s)?; (Defendants) Is the claimant a ‘visitor’?; What might be regarded as ‘premises’?; What is the common duty of care?; Has the common duty of care been breached? Did the breach cause damage? 1. The Occupier S(2) of the Act does not provide a statutory definition of occupiers, but instead refers to the old common law rules on identifying an occupier (Wheat v Lacon). The leading case here is: Wheat v E. Lacon & Co. Ltd [1966] AC 522 – A widow whose husband has fallen to his death down some unlit stairs in a public house. The widow sued the management of the pub and the brewery in negligence. Who are the occupiers? Lord Denning’s test. The test for occupation was one of control: 1 ‘[T]he 1957 Act has been very beneficial. It has rid us of those two unpleasant characters, the invitee and the licensee, who haunted the courts for years, and it has replaced them by the attractive character of the visitor who so far has given no trouble at all.’ Per Lord Denning in Roles v Nathan). 1 ‘Wherever a person has a sufficient degree of control over premises that he ought to realise that any failure on his part to use care may result in injury to a person coming lawfully there then he is an occupier and the person coming lawfully there is his visitor and the occupier is under a duty of care to his visitor’: per Lord Denning. Both the manger and the brewery as owners of the pub, were occupiers, it’s based on the neighbour principle. Can have more than one occupier and more than one defendant on one premises, don’t have to have a right of ownership to be an occupier. Harris v Birkenhead Corporation [1976] 1 All ER 341 –Doesn’t have to be a physical occupation of the space for a defendant to be an occupier. An empty terrace house which has been abandoned, a child fell threw one of the widows, because the glass was removed. The defendant’s local authority were the occupier of this, because they served a notice on the terrace of the house telling them to evacuate which showed control. Held – Defendant local authority was to be regarded as occupier – serving a notice on the tenants requiring them to leave demonstrated ‘sufficient control’. Even empty houses could have an occupier. Note : Landlords may or may not have sufficient control to qualify as an occupier at the time of an injury on the premises. Even if not occupiers, landlords may still be liable under Defective Premises Act 1972 – s of which states that if the lease provides that the landlord has an obligation regarding the repair/ maintenance of the property, the landlord will owe a duty of care to anyone who might reasonably be regarded as affected by a defect in the premises. 2. ‘Visitors’ S(2) again refers to the common law to identify visitors. Common law defines a ‘visitor’ as someone who has express or implied permission to be on the premises. Robson v Hallett [1967] 2 QB 939 – anyone who approaches the premises has an implied commission, but the occupier can withdraw this commission by e. adding a sign. per Lord Parker – ‘the occupier of any dwelling house gives implied [permission] to any member of the public coming on his lawful business to come through the gate, up the steps, and knock on the door of his house.’ Other forms of implied permission? The line between visitor and trespasser is not always easy to discern: Lowery v Walker [1911] AC 10 – Claimant injured by ‘a savage beast’ (a horse) when crossing D’s field to access the railway station, using it as a short cut. D was annoyed by this use of the land, so he put a savage horse to try to deter people and he added fences. C was beaten by the horse and sued the occupier in negligence. HoL: defendant had tolerated this trespass and that gave rise to an implied license therefore C was treated as a visitor - the occupier’s ‘tolerance’ of the repeated trespass gave rise to an implied licence. Comment: At the time of Lowry there was no protection for trespassers, judges thought it was irresponsible to put a horse if you knew that people cross it, so they added this remedy of a fictional device which renders the claimant a visitor in these situations. But now there is statutory provision, so the courts don’t need to use this fictional device of an implied license. Query the status of Lowery v Walker following the enactment of the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984 (below). See now also the case of: 2 bouncy castles (Perry v Harris [2008] EWCA Civ 907). 4. The Common Duty of Care S(2) – ‘The common duty of care is a duty to take such care as in all the circumstances of the case is reasonable to see that the visitor will be reasonably safe in using the premises for the purposes for which he is invited or permitted by the occupier to be there.’ In essence, the common duty of care replicates the ordinary duty of care established at common law. Only foreseeable risks are to be guarded against and only reasonable steps need to be taken. Not a duty to take precautions against every foreseeable risk. Duty of care arise automatically out of statute, so every visitor is owed a duty (no neighbour principle/tripartite test). The issue is to determine whether the duty has been breached. Note that the duty is to keep the visitor reasonably safe, not the premises. a) Applications of the Common Duty of Care Is the duty engaged at all? The judges have come up with this as a means of dismissing cases which are not claim worthy. The common duty of care is only engaged where the injury is attributable to a defect in the state of the premises as opposed to activities which the claimant has chosen to perform: Siddorn v Patel [2007] EWHC 1248 – D’s tenant was injured when he decided to dance on a sky light of D’s garage roof. Held - D not liable as the hazard was not due to the ‘state of the premises’ but the claimant’s activity. Darby v National Trust [2001] EWCA Civ 189 – no duty in respect of obvious risks – the claimant’s husband drowned whilst swimming in a pond on National Trust property. Although it was known that visitors did paddle and swim in the pond, no warning notices had been erected by the pond (cf the case of Tomlinson v Congleton below where notices had been erected). Held – the common duty of care did not extend to a requirement to warn visitors of obvious risks, ‘One or more notices saying ‘Danger, No Swimming’ would have told Mr Darby no more than he already knew.’ (per May LJ). Geary v JD Wetherspoon Plc [2011] EWHC 1506 b) The ‘Occupancy Duty’ versus the ‘Activity Duty’ Note that s(1) of the Act refers to “[T]he duty which an occupier owes to his visitors in respect of dangers due to the state of the premises or to things done or omitted to be done on them.” This would suggest that liability under the statute extends to injuries caused by the state of the premises (e. slates falling off a roof or collapsing stairs) and also to injuries caused by dangerous activities carried out on the premises, however the case law suggests otherwise: Ogwo v Taylor [1988] AC 431 – claimant was a firefighter, was called to the defendants house, D a set his house on fire, the injuries were due to activities on the land, so the case needs to be dealt under common law and not the OLA. As this was not a case of injury suffered due to the state of the premises but an activity on the premises, the case was dealt with under common law negligence rather than the Act. See also Bottomley v Todmorden [2003] EWCA Civ 1575; [2004] PIQR P18 – dangerous firework display dealt with at common law rather than under statute. 4 c) The Common Duty of Care as applied to Special Visitors: i) Children S(3)(a) – ‘an occupier must be prepared for children to be less careful than adults.’ S(3)(a) serves as a reminder to the occupier that children are naturally inquisitive and blind to risk. See also: Glasgow Corporation v Taylor [1922] 1 AC 44 – the doctrine of ‘allurement’ – i. something alluring or tempting but known to be dangerous if meddled with. Only applicable with children. Case decided before the OLA act. A boy (aged 7) died after eating poisonous berries from a plant (Atropa Belladonna) in a public park. It was known to the Ds that the berries were ‘alluring and tempting to children…but deadly poisonous’. Lord Atkin found that the D’s liability would probably rest upon the concept of allurement: ‘their knowledge that by their action they may bring children of tender years, unable to take care of themselves, yet inquisitive and easily tempted, into contact…with things alluring or tempting to them, and possibly in appearance harmless, but which, unknown to them and well known to the defendants, are hurtful or dangerous if meddled with.’ Occupiers were liable on the basis of the doctrine of allurement. What is the significance of an allurement? For a modern indication that the law can be more generous to the child claimant in occupiers’ liability, see Jolley v Sutton LBC [2000] 1 WLR 1082 where Lord Hoffmann said ‘it has been repeatedly said in cases about children that their ingenuity in finding unexpected ways of doing mischief to themselves and others should never be underestimated.’ Two teenage boys found an abandoned boat, tried to repair it to sail in it. It collapsed on one of the boys. Doctrine of allurement can apply even when the children are in their teens. The occupier’s duty to child visitors is clearly heightened by the fact that children cannot be expected to effectively safeguard themselves from injury and might predictably be tempted into dangerous situations. The duty is, on the other hand, limited by the fact that the occupier is entitled to expect that very young children will usually be supervised by a parent/guardian or other responsible person. See: Phipps v Rochester Corporation [1955] 1 QB 450 (note this case was decided before the 1984 Act which explains the use of the implied licence concept in favour of the child). Occupiers liability is limited by the fact that they should rely on parents to supervise the very young children. A boy (5) and his sister (7) walked across grassland near to their house onto a building site owned by the Ds. The boy fell into a trench on the building site and broke his leg. The occupiers were not liable because they were entitled to assume that prudent parents would not allow little children out unaccompanied. Per Devlin J: ‘the responsibility for the safety of little children must rest primarily upon the parents; it is their duty to see that such children are not allowed to wander about by themselves, or at the least to satisfy themselves that the places to which they do allow their children to go unaccompanied are safe for them to go to….. Different considerations may well apply to public parks or to recognized playing grounds where parents allow their children to go unaccompanied in the reasonable belief that they are safe.’ The usual rule is that responsibility rests on the parents. This doesn’t mean that the parents are liable, the liability is just limited. 5 was no suggestion that the skilled worker didn’t use their training to protect themselves, he was not owed a duty. The occupier was liable because they were negligent in starting the fire. How is this to be reconciled with Roles v Nathan? The sweeps didn’t use their skills and knowledge to protect their safety so a duty was owed. d) Means of Discharging the Duty i) Warnings When will a warning suffice to discharge the occupier’s duty? A warning is not necessarily enough, it depends on the circumstances (e. where you put the warning, contents of the warning). S(4)(a) - ‘…the warning is not to be treated without more as absolving the occupier from liability, unless in all the circumstances it was enough to enable the visitor to be reasonably safe.’ Roles v Nathan [1963] 1 WLR 1117 – Lord Denning MR considered that even if he had been wrong about no duty being owed to the chimney sweeps in respect of the risks of carbon monoxide poisoning, the occupiers had discharged their duty of care by giving repeated explicit warnings and even instructions not to go into the flu chamber. The warnings were sufficient to make the visitor reasonably safe. Where warnings are provided the placement/size of the warnings can render them incapable of fulfilling the common duty of care: McCarrick v Park Resorts [2012] EWHC B27 In some instances a warning would never be enough to discharge the occupier’s duty: Rae v Mars (UK) Ltd [1990] EG 80 NOTE: Be careful to distinguish warnings from exclusion notices! A sign which does not point to a particular hazard is unlikely to count as a warning notice. ii) Independent contractors When can an occupier discharge their duty by relying on the services of independent contractor? Only applied where the contractor is injured due to faulty construction. s(4)(b) ‘Where damage is caused to a visitor by a danger due to the faulty execution of any work of construction, repair or maintenance by an independent contractor employed by the occupier, the occupier is not to be treated without more as answerable for the danger if in all circumstances he had acted reasonably in entrusting the work to an independent contractor and had taken such steps (if any) as he reasonably ought to satisfy himself that the contractor was competent and that the work had been properly done.’ If the claimant’s damage was caused by the negligence of an independent contractor on the occupier’s premises, the occupier’s duty of care is discharged and he/she escapes liability, provided the occupier can demonstrate three things. These are that the occupier: i) was reasonable in entrusting the work to a contractor; ii) took reasonable steps to ensure that the contractor was competent; and iii) took reasonable steps to ensure that the work was properly done. Case law offers some guidance on how these provisos are to be applied: i) reasonableness of entrusting the work to an independent contractor: There is no case law, not proved to be an issue, because it is usually found reasonable to entrust any work to a contractor. ii) reasonableness of steps taken to ensure that the contractor was competent: Does this require the occupier to check the contractor has public liability insurance? 7 Issue on whether under s(4)(b) you have to check whether the contractor has public liability insurance. See: Bottomley v Todmorden Cricket Club [2003] EWCA Civ 1575; [2004] PIQR P18: – Ds had commissioned independent contractors to put on fireworks display for a charity event but had failed to ascertain that the contractor was competent. A visitor was injured, occupiers were being used because the contractors were not insured. CA found that the occupiers had not discharged their duty under s (4)(b) but they could have asked the contractors about their insurance. This is a general principle that even when you are dealing with a claim under common law, the courts will look at the acts to guide how they will deal with the claim. Falls short of imposing a freestanding duty to check insurance position, but instead makes a link between ensuring competence and enquiring as to insurance. And also: Gwilliam v West Hertfordshire Hospital NHS Trust [2002] WLR 1425: D occupier invited contractors to set up a splat-wall on their land. Claimant (63 years old) was injured because the trampoline had not been properly set up. There was no insurance so they proceed against the occupier, court of appeal makes a link between insurance and checking competence. Majority of court of appeal suggest that on these facts there was a duty to enquire whether the contractor was insured. The D were not in breach because they had asked, and were told that the contractors were insured. That was enough to not breach the duty as an occupier. per Woolf CJ - “The fact of insurance would go to their competence. If the firm did not hold itself out as being insured this would …suggest that they were unlikely to be a reputable firm.” See the dissenting judgment of Sedley LJ- says that there is no point in saying there is a duty to ask about insurance, because it does not make the visitors any safer. Neither of these cases appears to be authority for the proposition that in all cases, occupiers employing independent contractors must check the contractor’s insurance position to fulfil s(4)(b). There seems to be a suggestion in both cases that there is a duty to ask about insurance, as they were dealing with a dangerous situation. See also Naylor v Payling [2004] EWCA Civ 560 (in textbook) – is there a general duty to check a contractor’s insurance? iii) cases on steps taken to ensure that the work was done properly: When will the occupier be required to check the contractor’s work? Depends on the facts, what is reasonable to expect from the occupier? The more high skilled the contractors work, the less it is reasonable to ask. Haseldine v Daw [1941] 2 KB 343 – again decided before the 1957 Act - Def (landlord of a block of flats) contracted with a company of lift engineers to maintain and repair the lift on a monthly basis. A defect in the lift caused injuries to the plaintiff. There is a negligence claim against the occupier. Per Scott LJ at 356: ‘Having no technical skill he [the occupier] cannot rely on his own judgement, and the duty of care towards his [visitors] requires him to obtain and follow good technical advice.’ On these facts, the occupier was reasonable in not checking the work at all. 8 (a) from things done or to be done by a person in the course of a business (whether his own business or another’s); or (b) from the occupation of premises used for business purposes of the occupier. But note – the liability of an occupier of dangerous premises towards a person obtaining access to the premises for recreational or educational purposes, is not regarded as ‘business liability’, unless granting that person such access for the purposes concerned falls within the business purposes of the occupier. Can exclude liability, as long as it is reasonable, this is limited because it only applied to business liability. When talking about non-business liability, then common law applies and you can as an occupier exclude liability. When can occupier exclude liability? 1- A, a guest at O’s hotel, suffers injury in the hotel pool? – cannot exclude liability 2- B is invited to O’s home for a social gathering and suffers injury in the swimming pool in the back garden? - can exclude liability under common law because it is non-business liability. 3- C suffers spinal injury when he dives into a swimming pool in the sports centre at his university? – cannot exclude liability, because it falls within the universities business liability. 4- O invites local school children to his farm to help them learn about modern farming techniques. One of the pupils, D, drowns in a pond on farmer O’s land – would s apply? – if it’s part of the business, then they can’t exclude liability. 7. Defences - Volenti/acceptance of the risk: s(5) Possible for occupier to argue that the visitors accepted the risk of harm. Very rare for the volenti defence to be successfully used. For a recent application of the volenti defence see: Geary v JD Wetherspoon Plc [2011] EWHC 1506- claimant had chosen to slide down banisters and suffered injuries. Courts said that the injury arose out of what she chose to do, didn’t say that it was under s(4)(b). - Contributory Negligence Liability to Non-Visitors Pre-1984 Common Law Protection for Non-visitors Robert Addie & Sons v Dumbreck [1929] AC 358 – at common law the only duty owed to a trespasser, even a child trespasser, was a minimal duty to abstain from recklessly or deliberately causing harm. Courts stated that the only duty owed to trespassers is that you shouldn’t be reckless or deliberate as regards to the trespassers safety, negligence was not enough. ‘The trespasser comes on to the premises at his own risk. An occupier.. liable only where the injury is due to some wilful act involving something more than the absence of reasonable care. There must be some act done with the deliberate intention of doing harm to the trespasser, or at least some act done with reckless disregard of the presence of the trespasser.’ In recognition of years of judicial discontent with the rule in Addie (see e. Videan v British Transport Commission [1963] 2 QB 650) the House of Lords overturned Addie: British Railways Board v Herrington [1972] AC 877 – child trespasser was on a railway, was known to occupier that there were gaps and people were crossing the land but they hadn’t 10 done much to protect people from the risk. rejected Addie and suggested a ‘duty of common humanity’ owed to trespassers: ‘So the question whether an occupier is liable in respect of an accident to a trespasser on his land would depend on whether a conscientious humane man with his knowledge, skill and resources could reasonably have been expected to have done or refrained from doing before the accident something which would have avoided it.’ Per Lord Reid. Lord Reid makes it clear that we don’t need implied licences anymore. Subject element: what is reasonable will depend on what the defendant can afford. Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984 S(1)(a) states that the Act shall have effect, in place of the rules of the common law, to determine whether any duty is owed by a person as occupier of premises to persons other than his visitors ‘in respect of any risk of their suffering injury on the premises by reason of any danger due to the state of the premises or to things done or omitted to be done on them .’ 1. The Occupier S(2) refers to the common law for the definition of ‘occupier’ (see Wheat v Lacon above). 2. Non-visitors The Act does not refer to trespassers but rather ‘persons other than visitors.’ The Act therefore applies to non-visitors, a category which includes: a) Trespassers; b) People using a private right of way; and c) People exercising a lawful right of way under the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (s(1)) – i. ramblers). 3. The duty of care to non-visitors: Is the 1984 Act engaged? As with the 1957 Act, s(1) above makes it clear that the Act is only relevant to a claim where the injury is attributable to ‘a danger due to the state of the premises’ and will not apply where the injury is caused by the claimant choosing to engage in a dangerous activity: Tomlinson v Congleton Borough Council [2003] UKHL 47; [2004] 1 AC 46 – adult injured after diving from a standing position in a shallow part of a lake in the D’s country park. D had prominent notices posted around the lake saying ‘dangerous water: no swimming’ and had instructed the park rangers to distribute leaflets warning not to swim. The claimant is treated as a trespasser, because notices were placed, using the water in the way against the notice makes him a trespasser. “… the only risk arose out of what he chose to do and not out of the state of the premises.” Per Lord Hoffmann. This mirrors the position under the 57 Act (see Siddorn above). It also means that if the hazard is due to activities rather than the dangerous state of the premises, but the occupier is responsible for those activities, injury may be actionable at common law in negligence (but not under the Act): See: Revill v Newbury [1996] 1 All ER 291. – D occupier had taken extreme precautions against people stealing from his shed, he stayed up all night behind the shed door with a shotgun, when he heard people busting about outside he shot them through the door. The CA said this 11 putting a fence round a fire-escape or hiring an extra security guard. It is more likely that what will happen will be what, in due course, the judge found happened in this case. The Trust has now built a perimeter fence round the entire site; there is only one entrance; anyone coming in is asked their business; children are turned away. It is right to say that this has occurred not just because of Mr Keown's accident but also because of break-ins which happened subsequently. It is not unfair to say, however, that the hospital ground is becoming a bit like a fortress. The amenity which local people had of passing through the grounds to the neighbouring streets and which children had of harmlessly playing in the grounds has now been lost.’ (For a further example of s(3) applied in the context of a trespasser under 18 years of age, see: Northern Electric Distribution [2010] EWCA Civ 141.) Mann v The Content of the Duty S(4): ‘the duty is to take such care as is reasonable in all the circumstances of the case to see that he does not suffer injury on the premises by reason of the danger concerned.’ Unlike OLA 1957, this duty does not extend to property damage. It’s about the risks of personal injury. – it’s a more limited duty. Revill v Newbery – The OLAs were not the appropriate mechanism of liability, although the provisions of OLA 1984 were of guidance value to a common law claim. Warnings under the OLA 1984 S(5): ‘Any duty owed by virtue of this section in respect of a risk may, in an appropriate case, be discharged by taking such steps as are reasonable in all the circumstances of the case to give warning of the danger concerned or to discourage persons from incurring the risk.’ When will a warning discharge the occupier’s duty? As long as reasonable steps were taken to discourage people from incurring the risk. Don’t have to make non-visitors reasonably safe with your warning. So easier to discharge the duty by a warning. - A warning is more likely to discharge the duty where it is specific about the risk and how to avoid it The warning can fail to discharge the duty where it is unclear/confusing. A warning may not discharge the duty where the visitor/non visitor is too young to read or the language would not be understood. E. young children. Acceptance of the risk by the non-visitor S(6): ‘No duty is owed by virtue of this section to any person in respect of risks willingly accepted as his by that person (the question whether a risk was so accepted to be decided on the same principles as in other cases in which one person owes a duty of care to another).’ Possible for a non-visitor to bring a claim but their claim is defeated because they have consented to the risk. It’s not the case with someone who just come on the land without permission, they have consented to any risks, and otherwise the 1984 act would have no purpose. Exclusion of liability under the 1984 Act??? (EXAM) S(1) of UCTA does not refer to Occupiers Liability Act 1984, so it seems that UCTA does not apply here. Michael Jones article. 13 The issue of whether you can exclude liability under 1984 is a conundrum, it is not clear. UCTA and its prohibition on excluding liability doesn’t make any reference to liabilities under the 1984 act to non-visitors, so UCTA and its restrictions don’t seem to apply here. But that gives rise to a number of possibilities: - UCTA doesn’t apply so that means as an occupier, you can exclude liability at common law, still have the common law power. As long as you put notice up at the premises, and take reasonable steps to make people aware of it, you can exclude liability. - Under the 1984 act, for trespassers, you cannot exclude your liabilities at all. We don’t know because this has not been tested by case law. The whole idea of excluding liability to somebody is that you are putting a limit (no liability) on to your permission. Means that trespassers might be better protected than visitors, because you can sometimes exclude liability if it’s a visitor but not a trespasser. Recommended Reading: - J. Elvin, ‘Occupiers’ Liability, Free Will and the Dangers of a Compensation Culture.’ (2008) 8 Edinburgh Law Review 127 - W. Norris, ‘Duty of care and personal responsibility: occupiers, owners, organisers and individuals’ (2008) JPIL 187 - M. Jones, ‘The Occupier’s Liability Act 1984.’ (1984) Modern Law Review 713. - Tomlinson v Congleton Borough Council [2003] UKHL 47; [2004] 1 AC 46 14 Is the act ‘engaged’ at all? (Tomlinson v Congleton) If the act is engaged, does the duty of care arise? - S(3)(a) – query whether this is a ‘hazard’ at all? S(3)(b) – knowledge of trespasser in the vicinity? S(3)(c) – is it reasonable to offer protection? (warning would require little effort/expense therefore reasonable to expect provision of warning? Would likely make little difference? S is ‘innocent’ child trespasser) s(4)- content of the duty - could take into account – no duty to warn of obvious risks (Darby); occupiers can expect parents to exercise reasonable supervision of their children (Phipps v Rochester); not necessary to find occupier or parents at fault (Bourne/Perry). (Note - Although Phipps concerned visitors rather than trespassers, you can probably cross-refer in this way as long as you explain what you are doing). Cheryl’s claim - C = visitor BUT OLA ‘57 is not applicable – why? Claim arises at common law because the injury was caused by an ‘activity’ not state of the premises (Ogwo v Taylor). Exclusions of liability? - Effect of notice: seeks to exclude/negate liability. For Louis and Cheryl’s claim, UCTA 1977 applies – the attempted exclusion is ineffective because s prohibits exclusion of liability for personal injury or death caused by negligence. BUT query whether the exclusion notice would apply to S’s claim if he is a trespasser? 16

Occupiers Liability Handout

Module: Law of Tort (LAW209)

University: University of Liverpool

- Discover more from: