- Information

- AI Chat

Fundamentals of Nursing - Ch. 44 Pain Management - RN Nclex

Adult Health II (NUR 2211)

Hillsborough Community College

Recommended for you

Students also viewed

Related documents

- Saunders Ch. 6 Ethical and Legal Issues RN Nclex

- Saunders 7th Edition Integumentary Disorders of the Adult Client : Integumentary System RN Nclex

- Saunders Psychiatric Medications RN Nclex 68

- Saunders Foundations of Mental Health Nursing RN Nclex 64

- Saunders Mental Health Problems of the Adult Client RN Nclex

- Saunders Ch. 63 Immune Medications RN Nclex

Preview text

Pain Management

OBJECTIVES

- Describe the physiology of nociceptive pain.

- List the characteristics used to differentiate categories of pain.

- Identify the various factors that influence pain.

- Explain how cultural factors influence the pain experience.

- Demonstrate how to assess a patient experiencing pain.

- Contrast the characteristics of acute pain with those of chronic pain

- Explain the nursing guidelines for administering analgesics safely

- Explain various nonpharmacological and pharmacological approaches to treating pain.

- Identify barriers to effective pain management.

- Evaluate a patient’s response to pain interventions.

KEY TERMS

Acupressure, p. 1081 Acute pain, p. 1063 Addiction, p. 1091 Adjuvants, p. 1082 Analgesics, p. 1082 Biofeedback, p. 1079 Breakthrough cancer pain, p. 1089 Chronic pain, p. 1064 Cutaneous stimulation, p. 1080 Drug tolerance, p. 1091

Epidural analgesia, p. 1087

Guided imagery, p. 1079

Idiopathic pain, p. 1064

Local anesthesia, p. 1087

Modulation, p. 1062

Multimodal analgesia, p. 1084

Nociception, p. 1061

Opioids, p. 1082

Pain threshold, p. 1066

Pain tolerance, p. 1063

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), p. 1086

Perineural infusions, p. 1087

Physical dependence, p. 1091

Placebos, p. 1091

Pseudoaddiction, p. 1091

Regional anesthesia, p. 1087

Relaxation, p. 1079

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), p. 1080

Transduction, p. 1061

Transmission, p. 1061 Pain is a universal but individual experience and a condition that nurses encounter among patients in all seings. It is the most common reason for seeking health care, yet it is often underrecognized, misunderstood, and inadequately treated. A person in pain often feels distress or suffering and seeks relief. One of the major challenges of pain is that as a nurse you cannot see or feel a patient’s pain. It is purely subjective. No two people experience pain in the same way, and no two painful events create identical responses or feelings in a person. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines it as “an unpleasant, subjective sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (IASP, 2017). In the “Declaration of Montreal,” the IASP declared that access to pain management is a fundamental human right (IASP, 2018a).

Scientific Knowledge Base

Nature of Pain

The pain experience is complex, involving more than a single physiological sensation caused by a specific stimulus. It has physical, emotional, and cognitive components. It is subjective and highly individualized. It depletes a person’s energy and may contribute to chronic fatigue. It interferes with interpersonal relationships and influences the meaning of life. Left untreated, it may lead to serious physical, psychological, social, and financial consequences. Pain itself cannot be measured objectively. Only the patient knows whether pain is present and how the experience feels. However, careful assessment is critical as you assess the behaviors and physiological changes associated with pain. It is not the responsibility of a patient to prove that he or she is in pain; it is your responsibility to assess a patient’s condition and accept his or her subjective report.

Physiology of Pain

In contrast to pain being a first-person, subjective perception, nociception is defined as an observable activity in the nervous system in response to an adequate stimulus (third-person perspective) (Treede, 2018). Normal or nociceptive pain is the protective physiologic series of events that bring awareness of actual or potential tissue damage. There are four physiological processes of nociception: transduction, transmission, perception, and modulation (Das, 2015). A patient in pain cannot discriminate among the processes. Understanding each process helps you recognize factors that cause pain, symptoms that accompany it, and the rationale for selected therapies.

Transduction

Thermal, chemical, or mechanical stimuli can cause nociceptive pain when the amount of stimuli is strong enough to meet the activation threshold of nociceptors, which are specialized nerve endings distributed throughout the skin, muscles, joints, and viscera. Nociceptors are classified by the type of stimuli they respond to, and some nociceptors respond to multiple types of stimuli (polymodal nociceptors). Transduction is the process whereby an activated nociceptor converts energy produced by these stimuli (e., exposure to pressure or a hot surface) into an action potential.

Once transduction is complete, transmission of the nociceptive impulse begins. Inflammation caused by disease processes or cellular damage resulting from thermal, mechanical, or chemical stimuli cause the release of vasoactive and pro-nociceptive mediators such as prostaglandins, bradykinin, substance P, and histamine (Box 44). These substances directly affect the nerve fibers, lowering the threshold required to activate nociceptors and generating action potentials across the synaptic cleft, a process known as peripheral sensitization (Starkweather et al., 2016) (Fig. 44). Peripheral sensitization, which lowers the threshold for causing an action potential within the peripheral afferent neurons, can also result from changes in receptors, ion channels, and the amount neurotransmiers released.

B ox 4 4 .1 Neurophysiology of Pain: Neuroregulators

Neurotransmiers (Excitatory)

Prostaglandins

- Generated from the breakdown of phospholipids in cell membranes

- Thought to increase sensitivity to pain

Bradykinin

- Released from plasma that leaks from surrounding blood vessels at the site of tissue injury

- Binds to receptors on peripheral nerves, increasing pain stimuli

- Binds to cells that cause the chain reaction producing prostaglandins

Substance P

- Found in pain neurons of dorsal horn (excitatory peptide)

- Needed to transmit pain impulses from periphery to higher brain centers

- Causes vasodilation and edema

FIG. 44 Chemical synapses involve transmitter chemicals (neurotransmitters) that signal postsynaptic cells. From Patton KT, Thibodeau GA: Anatomy & physiology, ed 9, St Louis, 2016, Mosby.

Transmission

Each nociceptor has an axon composed of peripheral afferent nerve fibers that are either myelinated (A-delta fibers) or unmyelinated (C fibers). The nociceptive impulses are transmied from the periphery to the spinal cord via the peripheral afferent fibers to the dorsal root ganglia and the superficial lamina I/II of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The fast- transmiing myelinated A-delta fibers transmit sharp, localized nociceptive information, whereas the smaller-diameter unmyelinated C

fibers relay impulses that are dull, achy, and poorly localized. For example, after stepping on a nail, a person initially feels a sharp, localized pain, which is a result of A-fiber transmission, or first pain. Within a few seconds the whole foot aches from C-fiber transmission, or second pain (Steeds, 2016). The A-delta fibers transmit nociceptive impulses from the dorsal horn to the interior deeper laminae (III-IV) of the spinal cord and higher centers of the brain by way of the spinothalamic tracts (Fig. 44). Dorsal horn neurons carrying nociceptive input include projection neurons, local interneurons, and propriospinal neurons. Many of the projection neurons have axons that cross the midline and ascend to multiple areas of the brain, including the thalamus, gray maer of the cerebral cortex, the pons, and parts of the medullary reticular formation. It is through this cellular system of communication (action potentials carrying nociceptive input) that pain, arising from any area of the body including the nerve or areas of the brain itself, can be perceived by the individual.

Perception

Once a pain stimulus reaches the cerebral cortex, the brain interprets the quality of the pain and processes information from past experience, knowledge, and cultural associations in the perception of the pain (Fenton et al., 2015). Perception is the point at which a person is aware of nociceptive impulses and perceives pain. The somatosensory cortex identifies the location and intensity of pain, whereas the association cortex, primarily the limbic system, determines how a person feels about it. There is no single pain center. As a person becomes aware of pain, a complex reaction occurs. Psychological and cognitive factors interact with neurophysiological ones. Perception gives awareness and meaning to pain, resulting in a reaction. The reaction to pain includes the physiological and behavioral responses that occur after an individual perceives pain.

Modulation

Projection neurons activate endogenous descending inhibitory mediators (see Box 44), such as endorphins (endogenous opioids), serotonin, norepinephrine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), that aid in producing an analgesic effect. These mediators hinder the transmission of nociceptive impulses in the dorsal horn neurons. This inhibition of the pain impulse is the fourth and last phase of the normal pain process known as modulation (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Modulation can also occur through peripheral and/or central sensitization, resulting in increased perception of pain (Bourne et al., 2014). Afferent nerve fibers sensitized by vasoactive and pronociceptive mediators lower the threshold of activation and result in continuous nociceptive input to dorsal horn neurons and central sensitization. Clinical manifestations of central sensitization include expansion of the pain beyond the initial location, exaggerated response to noxious stimuli known as hyperalgesia, and pain in response to normally non-noxious stimuli, also called allodynia. A protective reflex response also occurs with pain (Fig. 44). A-delta fibers send sensory impulses to the spinal cord, where they synapse with spinal motor neurons. The motor impulses travel via a reflex arc along efferent (motor) nerve fibers back to a peripheral muscle near the site of stimulation, thus bypassing the brain. Contraction of the muscle leads to a protective withdrawal from the source of pain. For example, when you accidentally touch a hot iron, you feel a burning sensation, but your hand also reflexively withdraws from the surface of the iron. Pain perception

requires consciousness and an intact central nervous system. Common factors that disrupt the pain process include trauma, drugs, tumor growth, and metabolic disorders.

FIG. 44 Protective reflex to pain stimulus.

Gate-Control Theory of Pain

Melzack and Wall’s gate-control theory (1965) was the first to suggest that pain has emotional and cognitive components in addition to physical sensations. The theory explains how rubbing an injured area can reduce pain. The small-diameter fibers activated by noxious stimuli open the gate to pain transmission, and the large-diameter fibers have inhibitory effects to shut the gate. Rubbing the injured area promotes proprioceptive large- diameter fiber input and therefore inhibits further transmission of pain signals from small-diameter nerves to the brain. Melzack (1999) later proposed the neuromatrix theory of pain, postulating that each individual possesses a genetically determined neural matrix that develops and is

Behavioral Responses

The pain response is complex, influenced by a person’s culture, pain experiences, perception of pain, and ability to manage stress. If left untreated or unrelieved, pain significantly alters quality of life with physical and psychological consequences; this phenomenon is referred to as high-impact pain (Dahlhamer et al., 2018). The widespread effects of pain support why effective pain management is essential. Some patients choose not to report pain if they believe that it inconveniences others or if it signals loss of self-control. Others endure severe pain without asking for assistance. Clenching the teeth, facial grimacing, holding or guarding the painful part, and bent posture are common indications of acute pain. Chronic pain can affect a patient’s activity (eating, sleeping, socialization), thinking (confusion, forgetfulness), emotions (anger, depression, irritability), quality of life, and productivity (IOM, 2011). You soon learn to recognize paerns of behavior that reflect pain even when patients offer no verbal report, especially those with dementia or other cognitive changes. Recognizing a patient’s unique response to pain allows you to assess the success of pain-management therapies. Encourage your patients to accept pain-relieving measures so that they remain active and continue to maintain daily activities. A patient’s ability to tolerate pain significantly influences your perceptions of the degree of his or her discomfort. Patients who have a low pain tolerance (level of pain a person is willing to accept) are sometimes inaccurately perceived as complainers. Teach patients the importance of reporting their pain sooner rather than later to facilitate beer control and optimal functional status.

Acute and Chronic Pain

Pain is categorized by duration (acute or chronic) or pathological condition (e., cancer or neuropathic). The two types of pain that you observe in patients are acute (transient) and chronic (persistent), which includes cancer and noncancer pain.

Acute/Transient Pain

Acute pain is protective, usually has an identifiable cause, is of short duration, and has limited tissue damage and emotional response. It is common after acute injury, disease, or surgery. Acute pain warns people of injury or disease; thus it is protective. It eventually resolves, with or without treatment, after an injured area heals. Patients in acute pain are

frightened and anxious and expect relief quickly. It is self-limiting; therefore a patient knows that an end is in sight. Because acute pain has a predictable ending (healing) and an identifiable cause, health team members are usually willing to treat it aggressively. Acute pain seriously threatens a patient’s recovery by hampering his or her ability to become active and involved in self-care. This results in prolonged hospitalization from complications such as physical and emotional exhaustion, immobility, sleep deprivation, and pulmonary complications. Physical and psychological progress is delayed as long as acute pain persists because a patient focuses all energy on pain relief. Efforts aimed at teaching and motivating a patient toward self-care can be hindered until the pain is managed successfully. Complete pain relief is not always achievable, but reducing pain to a tolerable level is a realistic goal. A primary nursing goal is to provide pain relief that allows patients to participate in their recovery, prevent complications, and improve functional status. Unrelieved acute pain can progress to chronic pain.

Chronic/Persistent Noncancer Pain

Chronic pain affects more than 50 million American adults, and among those affected, nearly 20 million live with high-impact chronic pain (Dahlhamer et al., 2018). Unlike acute pain, chronic pain is not protective and thus serves no purpose, but it has a dramatic effect on a person’s quality of life. Chronic noncancer pain is ongoing or recurrent pain that lasts beyond the usual course of an acute illness or the healing of an injury (more than 3 to 6 months) and that adversely affects an individual’s well- being (ACPA, 2018). It does not always have an identifiable cause and leads to great personal suffering. Examples of chronic noncancer pain include arthritis, low back pain, headache, fibromyalgia, and peripheral neuropathy. It may result from an initial injury such as a back sprain, or there may be an ongoing cause such as illness. Chronic noncancer pain may be viewed as a disease since it has a distinct pathology that causes changes throughout the nervous system that may worsen over time. It has significant psychological and cognitive effects and can constitute a serious, separate disease entity itself. Chronic noncancer pain is usually non–life threatening. In some cases an injured area healed long ago, yet the pain is ongoing and does not respond to treatment. The possible unknown cause of chronic pain, combined with ineffective treatments and the unrelenting nature and uncertainty of its duration, frustrates a patient, frequently leading to psychological depression and even suicide. Chronic pain is a major cause of psychological and physical

completely assess reports of new pain by a patient with existing pain. Despite the availability and wide use of effective therapies and updated guidelines from reliable leading professional societies, the undertreatment of cancer pain is still frequent (Burchum and Rosenthal, 2019). Research shows that approximately one-third of patients who receive treatment for pain still do not receive pain medication proportional to their pain intensity (Greco et al., 2014).

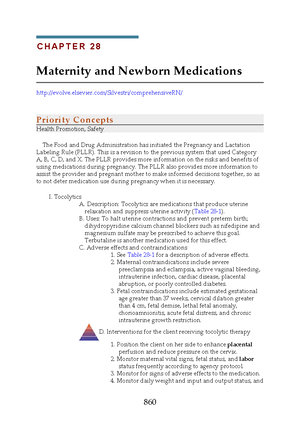

TABLE 44.

Classification of Pain By Inferred Pathology

From Pasero C, McCaffery M: Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, St Louis, 2011, Mosby.

Idiopathic Pain

Idiopathic pain is chronic pain in the absence of an identifiable physical or psychological cause or pain perceived as excessive for the extent of an organic pathological condition. An example of idiopathic pain is complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). Research is needed to beer identify the causes of idiopathic pain to identify more effective treatments.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Nursing knowledge of pain mechanisms and interventions continues to grow through nursing research. This section explores factors that influence the pain experience.

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs

Aitudes of nurses and other health care providers affect pain management. The traditional medical model of illness generates aitudes about pain. This model suggests that physical problems result from physical causes. Thus pain is a physical response to organic dysfunction. When there is no obvious source of pain (e., the patient with chronic low back pain or neuropathies), health care providers sometimes stereotype patients with pain as malingerers, complainers, or difficult patients. Studies of nurses’ aitudes regarding pain management show that a nurse’s personal opinion about a patient’s self-report of pain affects pain assessment and titration of medication doses. It has been shown that nurses’ assessment of pain intensity often underestimates patients’ pain reports (Goulet et al., 2013; Desai et al, 2014). Also, nurses may infer cues on pain severity solely from how pain is treated and then use the cues when making symptom judgments, often leading to underestimation and overestimation of pain (Dekel et al., 2016). Patients with a high self-report of pain, even when nurses are aware of their pain experience and analgesic treatment, are vulnerable to underestimation and hence to pain undertreatment (Dekel et al., 2016). Also, patients with a low self-report of pain are subject to overestimation and thus are exposed to overtreatment with potential treatment hazards. A number of nurse and patient variables, including cultural (e., gender, age, education), knowledge, and patient diagnosis, contribute to the differences in pain ratings. A study showed that patients treated by nurses who have postgraduate training and/or aend continuous education programs and who have greater autonomy in modifying pain treatment protocols experience beer quality of care (Tomaszek and Debska, 2018). Nurses’ assumptions about patients in pain seriously limit their ability to offer pain relief. Biases based on culture, education, and experience influence everyone. Too often nurses allow misconceptions about pain (Box 44) to affect their willingness to intervene. Clinical practices can also play a role. For example, when there are conditions of symptom uncertainty and ambiguous clinical judgment, nurses may incorrectly use

medical evidence cues alone and follow established clinical protocols or pathways that may simplify clinical decisions but will bias pain estimation (Dekel et al., 2016). Some nurses avoid acknowledging a patient’s pain because of their own fear and denial. They do not believe a patient’s report of pain if he or she does not appear to be in pain. A nurse is entitled to personal beliefs; however, he or she must accept a patient’s report of pain, act according to professional guidelines, standards, and position statements, and individualize appropriate policies and procedures, protocols, and evidence-based research findings (American Nurses Association, 2018).

B ox 4 4 .2 Common Biases and Misconceptions About

Pain

The following statements are false:

- Patients who abuse substances (e., use drugs or alcohol) overreact to discomforts.

- Patients with minor illnesses have less pain than those with severe physical alteration.

- Administering analgesics regularly leads to drug addiction.

- The amount of tissue damage in an injury accurately indicates pain intensity.

- Health care personnel are the best authorities on the nature of a patient’s pain.

- Psychogenic pain is not real.

- Chronic pain is psychological.

- Patients who are hospitalized experience pain.

- Patients who cannot speak do not feel pain.

To help a patient gain pain relief, it is important to view the experience through the patient’s eyes. Acknowledging a personal prejudice or misconception helps to address patient problems more professionally. When one becomes an active, knowledgeable observer of a patient in pain, it is possible to more objectively analyze the pain experience. The patient makes the diagnosis that pain is present, and the nurse provides interventions that ultimately offer relief.

Fundamentals of Nursing - Ch. 44 Pain Management - RN Nclex

Course: Adult Health II (NUR 2211)

University: Hillsborough Community College

- Discover more from:

Recommended for you

Students also viewed

Related documents

- Saunders Ch. 6 Ethical and Legal Issues RN Nclex

- Saunders 7th Edition Integumentary Disorders of the Adult Client : Integumentary System RN Nclex

- Saunders Psychiatric Medications RN Nclex 68

- Saunders Foundations of Mental Health Nursing RN Nclex 64

- Saunders Mental Health Problems of the Adult Client RN Nclex

- Saunders Ch. 63 Immune Medications RN Nclex