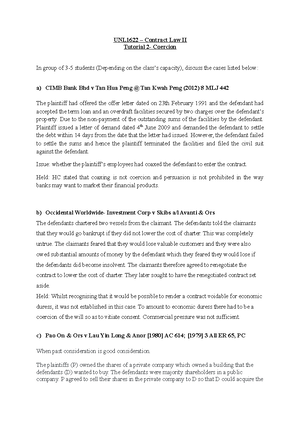

- Information

- AI Chat

CBE Answer scheme test

ACCA accounting (SBR P3)

Sunway University

Recommended for you

Preview text

CBE Answer

The consolidated financial statements of the Party Group are of little value when trying to assess the

performance and financial position of its subsidiary, Streamer Co. Therefore the main source of

information on which to base any investment decision would be Streamer Co’s individual financial

statements. However, where a company is part of a group, there is the potential for the financial

statements (of a subsidiary) to have been subject to the influence of related party transactions. In

the case of Streamer Co, there has been a considerable amount of post-acquisition trading with Party

Co and, because of the related party relationship, there is the possibility that this trading is not at

arm’s length (i. not at commercial rates). Indeed from the information in the question, Party Co

sells goods to Streamer Co at a much lower margin than it does to other third parties. This gives

Streamer Co a benefit which is likely to lead to higher profits (compared to what they would have

been if it had paid the market value for the goods purchased from Party Co). Had the sales of $8m

been priced at Party Co’s normal prices, they would have been sold to Streamer Co for $10·9 million

(at a margin of 25% these goods cost $6m; if sold at a normal margin of 45% they would have been

sold at $6m/55% x 100). This gives Streamer Co a trading ‘advantage’ of $4·9 million ($10·9 million –

$6 million). There may also be other aspects of the relationship where Party Co gives Streamer Co a

benefit which may not have happened had Streamer Co not been part of the group, e. access to

technology/research, cheap finance, etc. The main concern is that any information about the

‘benefits’ Party Co may have passed on to Streamer Co through related party transactions is difficult

to obtain from published sources. It may be that Party Co has deliberately ‘flattered’ Streamer Co’s

financial statements specifically in order to obtain a high sale price and a prospective purchaser

would not necessarily be able to determine that this had happened from either the consolidated or

entity financial statements.

Obtain and cast a schedule of intangible assets, detailing opening balances, amounts capitalised in the current year, amortisation and closing balances. Agree the closing balances to the general ledger, trial balance and draft financial statements. Discuss with the finance director the rationale for the three-year useful life and consider its reasonableness. Recalculate the amortisation charge for a sample of intangible assets which have commenced production and confirm it is in line with the amortisation policy of straight line over three years and that amortisation only commenced from the point of production. For the ten new projects, discuss with management the details of each project along with the stage of development and whether it has been capitalised or expensed. For those expensed as research, agree the costs incurred to invoices and supporting documentation and to inclusion in profit or loss. For those capitalised as development, agree costs incurred to invoices and confirm technically feasible by discussion with development managers or review of feasibility reports. Review market research reports to confirm Grapes Co. has the ability to sell the product once complete and probable future economic benefits will arise. Review the disclosures for intangible assets in the draft financial statements to verify that they are in accordance with IAS 38 Intangible Assets

Discuss with management the rationale for the changes to property, plant and equipment (PPE) depreciation rates, useful lives, residual values and depreciation methods and ascertain how these changes were arrived at. Confirm the reasonableness of these changes, by comparing the revised depreciation rates, useful lives and methods applied to PPE to industry averages and knowledge of the business. Review the capital expenditure budgets for the next few years to assess whether the revised asset lives correspond with the planned period until replacement of the relevant asset categories. Review the non-current asset register to assess if the revised depreciation rates have been applied Review and recalculate profits and losses on disposal of assets sold/scrapped in the year, to assess the reasonableness of the revised depreciation rates. Select a sample of PPE and recalculate the depreciation charge to ensure that the non- current assets register is correct and ensure that new depreciation rates have been appropriately applied. – Obtain a breakdown of depreciation by asset categories, compare to prior year; where significant changes have occurred, discuss with management and assess whether this change is reasonable. For asset categories where there have been a minimal number of additions and disposals, perform a proof in total calculation for the depreciation charged on PPE, discuss with management if significant fluctuations arise. Review the disclosure of the depreciation charges and policies in the draft financial statements and ensure it is in line with IAS 16 Property, Plant and Equipment.

1a

A PESTEL analysis is designed to identify external factors which are currently, or potentially, affecting an organisation. These factors are largely outside the control of the organisation, although if the organisation is large, or if it can unite with other organizations to form a powerful group, it might be able to successfully petition agencies, such as the government, which influence these external factors. However, in general, companies undertake a PESTEL analysis to understand the drivers in the external environment and to help them prepare an appropriate organisational response to such drivers. The PESTEL analysis contributes towards the threats and opportunities of the SWOT analysis. In such an analysis we should be able to identify internal strengths which allow us to counter threats and exploit opportunities. We should also be able to identify and address weaknesses which make us vulnerable to threats and unable to exploit opportunities. Addressing a threat might include withdrawing from the market place altogether. In the PESTEL analysis for MFP, we have been asked to identify external factors from the perspective of four elements of the PESTEL analysis: political, sociocultural, environmental and legal. We have been asked to comment on the likely effect ofsuch factors in the context of the strengths and weaknesses of MFP.

Political

The new government’s manifesto has declared its intentions to make it mandatory for employees to pay 5% of their gross pay into a pension scheme of their choice. The amount paid in will be matched by the employer. It proposes that it will be the responsibility of the employer to ensure that payments are made into a government authorised scheme and to process these payments, through automatic payroll deductions, every month. Possible implications:

An increase in labour costs of 5% due to the requirement to match the deduction of the employee. (2)

An increase in administration costs associated with setting up, monitoring and processing pension payments.

Possible demands for employees for pay rises to compensate them for the 5% of their gross income which the government intends to make them pay into a pension fund.

The cost of labour can be viewed as a competitive weakness of MFP. The fact that it pays its employees more than its competitors means that the 5% increase will have a larger absolute effect on its costs. Margins are already under pressure, and these proposals will lead to an increase in direct and indirect labour costs, cutting margins even further if prices are not increased. Although competitors will be affected, they will not be affected as much as MFP by these proposals.

Sociocultural

There are two significant sociocultural trends relevant to MFP. First, there is increased nostalgia for the perceived personal service of the past. This appears to be a consumer reaction against large supermarkets which have increasingly followed a low-cost, no-frills approach. These supermarkets are stacked intensively with low priced products and customer service is both impersonal and kept to a minimum. However, there is now a trend within society for customers to value personal service. MFP ranks first amongst supermarkets for personal service, and so this sociocultural trend provides an opportunity for MFP to stress and exploit its strengths in this area. Furthermore, it is unique in having a network of smaller shops and so what, from a cost perspective, might appear to be a

weakness, can be presented as a strength and emphasised in its marketing campaigns. Second, there is increased reaction against large supermarkets which pay high salaries to their management and significant dividends to their institutional shareholders. The concept of co-operative ownership, where employees and customers are also shareholders, appears to be increasingly popular. MFP is again unique in that it is the only top-ten supermarket chain which is a co-operative. It should seek to exploit this opportunity by stressing this in its marketing approach.

Legal

The recent extension of disability access legislation requires shops and supermarkets to provide customers with unattended access to all shelf areas within the store. The previous legislation just required shops and supermarkets to provide disability access to the store areas. However, many customers found that goods were out of reach when they were actually in the store. This extension to the legislation addresses this issue. Possible implications:

Re-arrangement of products within the store to allow compliance with this legislation. Failure to comply will lead to $1,000 fines per incident.

Possible reduction in stock displayed in the store because of reduction in high level storage.

Overall, this should have minimal effect if stock is held in external storage areas and moved to the shelves when required. This may be a problem in the smaller stores, where storage space might be at a premium, so again the small size of these stores is a weakness. However, the requirements of this legislation might be the stimulus MFP requires to streamline its supply chain and achieve economies. It is recognised that MFP has weaknesses in this area and has not exploited technological advances in product control, movement and storage. This threat from legislation provides an opportunity for addressing this weakness. This may also be an area where competitors are at a disadvantage. The ‘pile it high’ approach associated with no-frills retailing may be incompatible with the legislation.

Environmental

Some consumers are increasingly concerned about the environmental impact of food and other products which they are purchasing. This is not only in terms of the excessive and elaborate packaging of the goods, but also in terms of the ‘food miles’ which the product has travelled before it reaches the shelves of the shop or supermarket. MFP has always been sensitive to these green consumers, for example, by ensuring that new shops and supermarkets are energy efficient. It is aware that this image of environmental sensitivity, combined with its status as a co-operative, makes it the supermarket of choice for many such consumers. It is also aware that the average wealth of these consumers is above the national average. This image of environmental sensitivity can be reinforced by:

Ensuring minimal packaging, or charging for packaging. As well as stressing the company’s green credentials, this also has the practical effect of bringing down costs and improving profit margins.

Stressing that local shops means fewer food miles. This is an advantage which MFP has over its competitors who have concentrated on building large stores to serve big catchment areas. Again, the network of local shops can be presented as a strength of the company.

Overall, exploiting external issues which concern the green consumer exploits a strength of MFP and these opportunities seem likely to continue into the future.

1b

Although customers are individual consumers, their bargaining power is relatively high and this is why supermarkets are so sensitive to price and so keen to establish schemes which tie the customer in some way, such as loyalty cards. At MFP the dividend scheme for customers plays such a role. The bargaining power of customers (buyers) is high because:

Alternative sources of supply (shops and supermarkets) are available and easy to find. Switching costs are very low, from one supplier to another. In fact, if the customer is not in a loyalty scheme, then there are effectively no switching costs; Customers have knowledge about prices of products from the marketing campaigns of competitors. For certain products and services, comparison websites provide pricing information across a range of suppliers.

In contrast, the bargaining power of suppliers is low. A number of factors contribute to this:

The customers of the suppliers (the supermarkets) are much larger and more concentrated than their suppliers. In fact they are so large that they can usually dictate terms and prices of supply. This is essentially how margins are preserved. Lower prices to entice customers are paid for by lower prices paid to suppliers. The switching costs from one supplier to another are generally very low, and indeed suppliers often compete with one another for the privilege of having supermarkets stock their products. MFP’s stance on ethical sourcing will almost certainly give them a price disadvantage because of higher payments to suppliers. Consequently, it has to be sure that customers are aware of the sourcing of the product and that they are also willing to pay a price premium for it.

The threat of new entrants should be relatively low. After all, substantial investment in infrastructure and marketing will be required to compete with the established supermarkets, who enjoy economies of scale and strong brand identities. Any new entrant might also have to establish its own distribution channels and will be entering a competitive market where aggressive marketing and price wars are rife. However, despite this, evidence from the scenario shows that two major supermarkets from overseas have entered the market in the last five years and made considerable gains. Both were well established in their own countries and so presumably had the capital to invest and the expertise to exploit the Arborian market. They also entered using a low-cost, no-frills model which distinguished them from established supermarkets. So, the threat of further new entrants from overseas remains, particularly as the Arborian economy remains strong.

The five forces framework also considers the threat of substitute products. In this context, supermarkets are essentially a mechanism for selling goods and services to the public. They were substitutes for the network of smaller shops which provided this in the past. In a sense, the smaller shops which remain are potential substitutes for the supermarkets, particularly now that sociocultural trends suggest that these should be valued, rather than avoided as uneconomic and inconvenient. Again, MFP is in a good place, as it can position itself as an organisation which recognises the relative values of both supermarkets and shops. A more significant substitute would be the direct supply of goods from suppliers to end customers. This indeed could be a virtual supermarket with customers picking products online and having them delivered directly to their home. In fact, many supermarkets already offer this service, although products tend to be selected from the physical supermarkets which customers can visit. However, there may be no need for such physical locations in the future, products might be held in large warehouses inaccessible to the public, or by the suppliers themselves who are given orders from the ‘supermarkets’ for products which are directly sent to the customer. This threat of substitution should be acknowledged because many trades and shops traditionally on the high street have disappeared to be replaced by virtual substitutes. Many bookshops and toy shops have closed to be replaced by online alternatives. Finally, the framework considers the competitive rivalry in the industry itself. This is relatively high because:

As we have discussed already, buyers can easily switch from one supplier to another. Products (in this context, supermarkets) are not particularly well differentiated and so there is little brand loyalty. Thus schemes to try to encourage brand loyalty (vouchers, loyalty cards, customer account discounts) are rife. Given how much investment is required to enter the industry, the consequent exit costs are high. The industry has relatively high fixed costs and so responding to price pressure is difficult. The usual response to such price pressure is to transfer this pressure to suppliers and to find, or demand, cheaper supply prices. There are many competing firms and potential substitutes.

However, despite this, the industry appears to still be attractive to a limited number of new entrants. The market has grown by almost 17% in the last five years and so this increased capacity in the market place has been particularly exploited by overseas-based supermarkets. MFP’s revenues have increased by 10% over this period, which is almost as much as HypCo, the country’s largest supermarket. Arboria remains a wealthy country and its economy is still growing and so the market may continue to expand, easing competitive pressure.

Q

The underlying cultural issues that would explain the failure of the Director General’s strategy at the National Museum can be explored using the cultural web. It can be used to understand the behaviours of an organisation – the day-today way in which the organisation operates – and the taken-for-granted assumptions that lie at the core of an organisation’s culture. The question suggests that it was a lack of understanding of the National Museum’s culture that lay at the heart of the Director General’s failure. In this suggested answer the cultural web is used as a way of exploring the failure of the Director General’s strategy from a cultural perspective. However, other appropriate models and frameworks that explore the cultural perspective will also be given credit.

A cultural web for the National Museum is suggested in Figure 1. The cultural web is made up of a set of factors that overlap and reinforce each other. The symbols explore the logos, offices, titles and terminology of the organisation. The large offices, the special dining room and the dedicated personal assistants are clear symbols of hierarchy and power in the museum. Furthermore, the language used by directors in their stories (see below) suggests a certain amount of disdain for both customers and managers. The status of professor conferred on section heads with Heritage Collections also provides relative status within the heads of collection sections themselves. The proposal of the Director General to close the heads’ dining room and to remove their dedicated personal assistants would take away two important symbols of status and is likely to be an unpopular suggestion.

The power structures of the organisation are significant. Power can be seen as the ability of certain groups to persuade or coerce others to follow a certain course of action. At present, power is vested in the heads of collection sections, reflected by their dominance on the Board of Directors. Three of the five directors represent collection sections. Similarly the Board of Trustees is dominated by people who are well-known and respected in academic fields relevant to the museum’s collections. The power of external stakeholders (such as the government) has, until the election of the new government, been relatively weak. They have merely handed over funding for the trustees to distribute. The Director General of the museum has been a part-time post. The appointment of an external, fulltime Director General with private sector experience threatens this power base and his suggestion for the new organisation structure takes away the dominance of the collection heads. On his proposed board, only one of six directors represents the collection sections.

The government funds the purchase and maintenance of artefacts that represent this heritage and culture

Q

i.

Claims of employees and customers A stakeholder ‘claim’ is the nature of the relationship between the stakeholder and the organisation. It describes what the stakeholder is seeking from its relationship: what it ‘wants’. In some cases, the nature of the claim is clear and meaningfully articulated but in others, it is unclear, amorphous and unvoiced. The claims of employees and customers are usually clear, with both being articulated in part by market mechanisms and in part by occasional collective representation. This means that unhappy employees leave and unhappy customers stop buying from the business. The employees of Cornflower, located in Athland, are likely to seek fairer terms and conditions, a safer workplace, both physically and psychologically, and more secure employment and better pay from their employers. In some countries, trade unions or labour pressure groups can express the collective will (claim) of employees. The PWR is an example of this. In contrast, Cornflower’s customers, such as Cheapkit, are looking for a continuing supply of cheap garments. Cheapkit’s business strategy is based upon the assumption that such supply will be available, and Cheapkit will have invested in capital (land and buildings) basing its strategy on the assumption of continuing supply at low unit prices. Cheapkit therefore has an incentive to maintain the pressure on Cornflower to minimise its costs, including labour costs. Conflicts in the claims A potential conflict between the claims of the customers, such as Cheapkit, and employees is in the control of costs at Cornflower. Because Athland is weakly regulated and corruption seems to be tolerated, Cornflower is able to employ local people on ‘zero hours’ contracts and, in the opinion of some, on ‘exploitative wages’. So the price of helping Cheapkit achieve its low cost position in its own market (the customer), is paid for in part by the poor terms and conditions of Cornflower’s employees in Athland. Were Cornflower’s employees to receive improved terms and conditions, including working in a safe environment, extended job security and higher rates of pay, these increased costs could make it more difficult for Cornflower to retain its low prices to Cheapkit and hence to Cheapkit’s customers.

ii.

Explain corruption

Corruption can be loosely defined as deviation from honest behaviour but it also implies dishonest dealing, self-serving bias, underhandedness, a lack of transparency, abuse of systems and procedures, exercising undue influence and unfairly attempting to influence. It refers to illegal or unethical practices which damage the fabric of society. In the case of Cornflower, the Fusilli brothers seemed to have few ethical problems with attempting to influence a number of activities and procedures in their perceived favour. There was seemingly little attempt to allow processes to take their course or to comply in detail with regulations.

Corruption at Cornflower

The case describes Athland as a country with weak regulatory controls. It is evident from the case that Athland did have the requisite regulation in place over such important matters as building construction, escape routes and building occupancy. The problem was the effectiveness of the state in enforcing that regulation. The first incidence of corruption in the case was the employment of inferior building materials. The motivation behind this was to achieve a lower total capital outlay for

the building and also a quicker completion time on the project. In both cases, the intention was to make the capital investment lower, presumably to reduce the debt created by the construction and hence the debt servicing costs. Where building regulations specify a certain quality of material, it is usually because that grade or quality is necessary to ensure the safety and integrity of the building when used and under stress. Likewise, bribes were offered to persuade officials to provide a weak level of inspection (effectively to ignore the regulations) when the building work was being carried out. It is common for building inspectors to be present during construction to ensure that relevant regulations are being adhered to. The Fusilli brothers corrupted these officials to the point where they did not adequately perform their duties. In doing so, the officials failed in their duty to the public interest and were complicit in the weak construction that, in turn, contributed to the building’s collapse. Because of the pressure on internal space in the new building, as well as the additional costs involved, the Fusilli brothers were able to have the building completed without the requisite number of escape routes. In the event of an emergency such as a fire or similar, the ability of people to leave the building quickly and safely would be a major determinant of casualty and death statistics. Because each escape route takes up a physical amount of space (with the door itself and the pathway needed to allow passage to the door), the space available for machines and other value-adding activity would be reduced and the building would be more costly to construct. This explains the Fusilli brothers’ motive to make this illegal change to the plans. More people may have been able to evacuate the building were such regulations adhered to and a safe number of escape routes provided. Finally, the occupancy rules were not enforced by officials. The number of occupants in a building is a legal constraint intended to ensure that over-occupation does not lead to accidents or other safety hazards. The number of people in the building is also a determinant of the evacuation time and, in turn, the risk to the safety of the occupants in the event of collapse. The fact that three times the regulated number of people worked in the building meant that escape plans were rendered much less effective and this would have significantly contributed to the casualties.

iii.

Exchange rate risk

Most international transactions involve a currency exchange (unless the countries are in a single currency trading block). Cheapkit needs to pay Cornflower in the currency of Athland whilst selling the garments in its home currency. Because currencies rise and fall against each other as a result of supply and demand for those currencies, an adverse movement of one against the other can mean that the cost of a transaction in one currency becomes more expensive because of that adverse movement. The loss incurred by that adverse movement multiplied by the company’s financial exposure is the hazard or impact of exchange rate risk. The loss to Cheapkit’s shareholders can take several forms. The most obvious is the actual loss incurred by an increase in the value of Athland’s currency against its own and the consequent increase in costs. This can be a material cost, affecting the buying decision, or it can add to Cheapkit’s expenses and therefore reduce its profits on the purchases from Cornflower. In addition though, a large amount of exposure to exchange rate risks can incur risk management costs such as exchange rate ‘hedging’, as well as the increased uncertainty over the volatility of Cheapkit’s profits.

Supply risk

This is the risk that Cheapkit will not be able to obtain the inputs it needs (in this case, garments at the right quality and cost) to sell in its own stores. Increased supply risk is usually associated with complicated or undeveloped supply chains, and dealing with weaker companies in poorly regulated countries. In this case, the collapse of Cornflower’s building in Athland means that, at least in the short term, Cornflower will have difficulty in meeting Cheapkit’s need for supplies and so this risk has

Cheapkit is a legal, and legally-compliant company, conducting its business in a responsible and diligent manner. It wishes to reassure investors and others that it takes the criticisms made by the PWR leader, Miss Jess Lui, very seriously. We would like to respond to points made in her well- publicised public letter to the board, and also to comment on points raised by several financial journalists about the company’s stance on the relatively recent integrated reporting initiative. Any media questions over and above these remarks can, of course, be made to the investor relations department as usual.

i. Citizenship

The company resents and strongly refutes any allegations that it has been a poor or irresponsible corporate citizen. Cheapkit recognises its role as a citizen, both here in its home country but also in Athland and elsewhere in the world in which it transacts. The board accepts two aspects of citizenship. First, any company such as Cheapkit, with its substantial footprint in society, has to acknowledge its responsibilities. Just as an individual has the responsibility to obey the law, fit in with the social and ethical norms of society, and behave in an appropriate way, so does a business. Cheapkit is a major employer in its home country and, through its supply chains into countries such as Athland, has a large social and economic impact. Its responsibility is to always comply with the laws and social norms which apply in each country it deals with. This extends to being a good employer, maintaining prompt payment of payables accounts, encouraging good working conditions at supplier companies and similar areas of good business practice. A second and equally important aspect of citizenship, however, is the exercise of rights. Cheapkit is a business conducting legal contracts with suppliers, and selling legal products. As such, it has the right to be protected by the law in the pursuit of its normal business activities. In addition, it has the right to receive the support of society in the pursuit of business in terms of its investors, employees and customers. It has the right, in other words, to have customers free to purchase products without feeling bad about it, and have employees happy to work for the company without fear of criticism from people believing themselves to be in a superior moral position. The Cheapkit board would remind people that it was not us who occasioned the tragic collapse of the Cornflower building in Athland. It was the negligence and corruption of parties outside our control, and therefore it is unfair to implicate Cheapkit in any criticism directed at Cornflower

ii. Accountability and fiduciary duty

We would like to take this opportunity to address two other important subjects, raised in recent media coverage about Cheapkit: the important issues of accountability and fiduciary duty. Again, we feel that much of what has been said has been misplaced and subjective, and we would like to provide comment to counter some of this commentary. The board of Cheapkit recognises its accountabilities in several ways. We accept the conventional understanding of accountability as an ability to call to account and to accept responsibility for something. Of course, a large business like Cheapkit has many accountabilities including our primary accountability to shareholders. This primary accountability is discharged in part using accounting statements and annual shareholder meetings, although integrated reporting (see later in this statement) may enhance this accountability further. This is not to say that we are unwilling to work with suppliers, as necessary, to help to improve their employee conditions. In fact, we fully recognise that such improvements would be to Cheapkit’s advantage as well as to the employees of Cornflower. Miss Lui’s letter made reference to her belief that Cheapkit has accountabilities beyond that, including our willingness to be called to account for events in our supply chain. This is a matter of ethical opinion. It may be a legitimate view but the board of Cheapkit does not share it. It is unreasonable for us to accept responsibility for events over which we have no direct authority or control. Cheapkit recognises its accountability to its shareholders to deliver

sustainable returns and would challenge any view which suggests it should be held to account for the behaviour of others in the supply chain, such as Cornflower. The board also recognises a fiduciary duty it owes to a range of stakeholders. A fiduciary duty, often understood in terms of a duty of care and trust which one party owes to another, can be legal or ethical. Cheapkit has legal fiduciary duties to its shareholders and employees in that it must comply with relevant laws and regulations relating to how these are dealt with under its duty of care. The board of Cheapkit is appointed to act in the fiduciary interest of its shareholders and must express this through the pursuit of profitable strategies and the management of strategic risks. As already stated, the extent to which Cheapkit has a fiduciary duty to other constituencies with whom it has no contractual relationship is a matter of ethical perspective. Miss Lui is of the view that the fact that we purchase from a certain supplier makes Cheapkit complicit in illegal and unethical practice at that company. The construction of the building and the conditions of employment for Cornflower’s employees is a not a matter over which Cheapkit has any fiduciary duty as this was entirely within the control of Cornflower’s management. Some have said that it was Cheapkit’s pressure for cheap prices from Cornflower which created the conditions for the tragic events to occur, but Cornflower freely entered into contracts with Cheapkit at agreed prices and was free to withdraw from those contracts if it did not feel able to deliver. Cheapkit’s fiduciary duties extend to, and include those, who collectively own the company, the shareholders, and those with whom the company is legally contracted to extend its duty of care, which is mainly its employees.

iii. Integrated reporting

The Cheapkit board would also like to take this opportunity to respond to some comments made on the usefulness of the relatively recent IIRC initiative and how this might affect the company and its reporting. Like many of the large companies on the world’s stock exchanges, Cheapkit is an enthusiastic supporter of integrated reporting (IR). We see it having a number of potential benefits to the company and its shareholders, but importantly, for many of its other stakeholders also. Designed to be an approach to reporting which accurately conveys an organisation’s business model and its sources of value creation over time, the IR model recognises six types of capital, with these being consumed by a business and also created as part of its business processes. It is the way that capitals are consumed, transformed and created which is at the heart of the IR model.

As readers of the business press will be aware, the six capital types are financial capital, manufactured capital, intellectual capital, social and relationship capital, human capital and natural capital. Cheapkit sees three substantial advantages of measuring and reporting performance against these types of capital. First, the need to report on each type of capital would create and enhance a system of internal measurement at Cheapkit which would record and monitor each type for the purposes of reporting. So the need to report on human capital, for example, would mean that Cheapkit and other companies adopting IR must have systems in place to measure, according to the IIRC guidelines, ‘competences, capabilities and experience and their motivations... including loyalties [and]... ability to lead, manage and collaborate’. These systems would support the company’s internal controls and make the company more accountable in that it would have more metrics upon which to report. Second, the information disclosed, once audited and published, would create a fuller and more detailed account of the sources of added value, and threats to value (i. risks), for shareholders and others. Rather than merely recording financial data in an annual report, the IR guidelines would enable Cheapkit to show its shareholders and other readers, how it has accumulated, transferred or disposed of different types of capital over the accounting period. So it would have to report, for example, on the social capital it has consumed, transformed and created and this could include issues of relevance to Miss Lui and others. It might include, for example, the jobs it has created or sustained in its supply chain and the social value of those jobs in their communities, or how it

CBE Answer scheme test

Course: ACCA accounting (SBR P3)

University: Sunway University

- Discover more from: