- Information

- AI Chat

Was this document helpful?

Principles - More lecture

Course: Industrial Engineering (ERGO1)

80 Documents

Students shared 80 documents in this course

University: University of the Assumption

Was this document helpful?

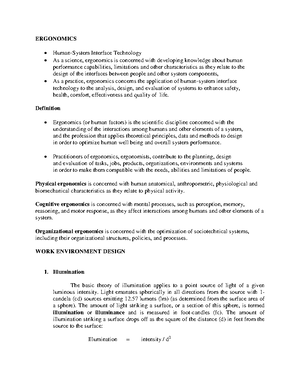

Principles (Concepts & Laws)

Systems thinking is a discipline used to understand systems to provide a desired effect; the

system for thinking about systems. It provides methods for “seeing wholes and a framework for

seeing interrelationships rather than things, for seeing patterns of change rather than static

snapshots.” The intent is to increase understanding and determine the point of “highest

leverage”, the places in the system where a small change can make a big impact.

Here are six foundational principles that drive systems thinking methods.

1. Wholeness and Interaction

The whole is greater than the sum of its parts (the property of the whole, not the

property of the parts; The product of interactions, not the sum of actions of the parts)

2. Openness

Living systems can only be understood in the context of its environment.

3. Patterns

To identify uniformity or similarity that exists in multiple entities or at multiple times.

4. Purposefulness

What you know about how they do what they do leads to understanding WHY they do

what they do.

Multidimensionality

To see complementary relations in opposing tendencies and to create feasible wholes with

infeasible parts.

Counterintuitive

That actions intended to produce a desired outcome may generate opposite results.

Introduction

Everything in this world, and indeed the universe, is connected to something else and is part of

something bigger. Our actions have wide consequences that affect people, organizations and

society around us. These consequences may be negligible or significant; they may be immediate

or several years down the line. Have you ever made a decision or done something expecting

one outcome, but the result was quite different and quite unexpected? Most of us have had

this experience. It might have happened in the school playground, in a sports team, on a social

network with family and friends, or at work. In fact, the world’s history is full of examples of

unintended consequences. Two such examples include:

In Borneo in the 1950s, to eliminate the problem of malaria, the World Health Organization

recommended spraying DDT pesticide to kill the carrier mosquitos; it had two unrelated

consequences. First, DDT also killed a species of wasp that controlled the population of

caterpillars. Most roofs of Borneo houses are made of thatch, and with natural pest control

gone the roofs started to collapse. Second, DDT affected other insects which were a food

source for geckos. Although geckos could tolerate the DDT in their bodies it stayed in their

system for long enough to kill the population of cats that ate them. With the cats gone the

island’s population of rats exploded, resulting in the destruction of grain stores and a dramatic

increase in the plague. They ended up parachuting cats back into Borneo to address the

problem (O’Shaughnessy, 2008).

The global financial crisis of 2008 was caused by a downturn in the US housing market and a

rising number of borrowers unable to repay their loans, and it spread throughout the world.

The underlying cause of the crisis was the confidence that the strong economic growth