- Information

- AI Chat

Was this document helpful?

APGov SC 1803 Marbury - N/A

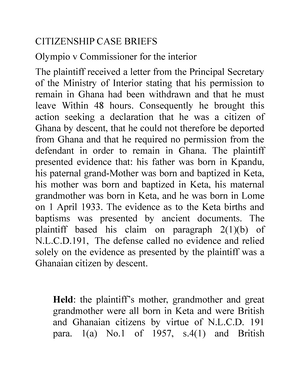

Course: Constitutional law of Ghana and its history (FLAW306)

346 Documents

Students shared 346 documents in this course

University: University of Ghana

Was this document helpful?

AP American Government Required Supreme Court Cases

Marbury v. Madison, 1803

S y n o p s i s o f t h e C a s e

In the fiercely contested U.S. presidential election of 1800, the three major candidates were Thomas Jefferson, Aaron Burr,

and incumbent John Adams. Adams finished third. As the results of the election became clear in early 1801, Adams and

his Federalist Party were determined to exercise their influence in the weeks remaining before Jefferson took office on

March 4, 1801, and did all they could to fill federal offices with "anti-Jeffersonians" who were loyal to the Federalists.

On March 2, 1801, just two days before his presidential term was to end, Adams nominated nearly 60 Federalist supporters

to positions the Federalist-controlled Congress had newly created. These appointees – known as the "Midnight Judges" –

included William Marbury, a prosperous financier from Maryland. An ardent Federalist, Marbury was active in Maryland

politics and a vigorous supporter of the Adams presidency.

The following day, March 3, Adams's nominations were approved en masse by the U.S. Senate. The commissions were

immediately signed and sealed by Adams's Secretary of State, John Marshall, who had been named the new Chief Justice of

the Supreme Court in January but continued acting as Adams's Secretary of State until Jefferson took office. The

commissions needed to be delivered to the appointees, and so Marshall dispatched his younger brother James Marshall to

deliver them. With only one day left before Jefferson's inauguration, James Marshall was able to deliver most of the

commissions, but a few – including Marbury's – were not delivered.

On March 4, 1801, Thomas Jefferson was sworn in and became the 3rd President of the United States. As soon as he was

able, Jefferson instructed his new Secretary of State, James Madison, to withhold the undelivered appointments. In

Jefferson's opinion, the commissions were void because they had not been delivered in time. Without the commissions, the

appointees were unable to assume the offices and duties to which they had been appointed. In December 1801, Marbury

filed suit against Madison in the Supreme Court, asking the Court to issue a writ of mandamus forcing Madison to deliver

Marbury's commission. This lawsuit resulted in the case of Marbury v. Madison.

Aside from its inherent legal complexities, the case created a difficult political dilemma for Marshall and the rest of the

Supreme Court. If the Court ruled in favor of Marbury and issued a writ of mandamus ordering Madison to deliver the

commission, Jefferson and Madison would likely have simply ignored the order, which would have made the Court look

powerless and emphasized the "shakiness" of the judiciary. On the other hand, a bare ruling against Marbury would have

given Jefferson and his Republican-Democrat Party a clear political victory.

J u d g e m e n t:

The 4 – 0 decision (due to illness, two of the six justices were unavailable to hear the case) expanded the power of the

Supreme Court in general, by announcing that the 1789 law which (it was claimed) gave the Court jurisdiction in this case

was unconstitutional. Marbury thus lost his case, which the Court said he should have won, but, in explaining its inability to

provide Marbury the remedy it said he deserved, the Court established the principle of judicial review, ie, the power to

declare a law unconstitutional

Chief Justice Marshall structured the Court’s opinion around a series of three questions: (1) did Marbury have a right to his

commission? (2) if Marbury had a right to his commission, was there legal remedy for him to obtain it, and (3) if there was

such a remedy, count the Supreme Court legally issue it?

C o u r t J u d i c i a l I n t e r p r e t a t i o n

On Question One

➢ Marshall wrote that Marbury had a right to his commission because all appropriate procedures were followed – the

commission had been properly signed and sealed. While Madison contended that the commissions were void if not

delivered, the Court disagreed in saying that the delivery of the commission was merely a custom, not an essential

element of the commission itself.

On Question Two

➢ The Court ruled that the laws clearly afforded Marbury a remedy. As a general matter, Marshall said, the law

provides remedies: "The very essence of civil liberty certainly consists in the right of every individual to claim the

protection of the laws whenever he receives an injury." The specific issue, however, was whether the courts (part of

the judicial branch of the government) could give Marbury a remedy against Madison (who as Secretary of State

was part of the executive branch of the government.) The Court held that so long as the remedy involved a

mandatory duty to a specific person, and not a political matter left to discretion, the courts could provide the legal

remedy. Marshall wrote: "The government of the United States has been emphatically termed a government of

laws, and not of men."

On Question Three

Students also viewed

- Judgment PS Investment V Ceredec & ORS-1

- Republic v Tommy Thompson Books L TD and Others

- Yakubu Awbego Vrs. Tindana Agongo Akubayela ; Immovable property – Allodial title to land, ownership of land, traditional evidence, resolution of conflicts arising from traditional evidence

- Police Service ACT, 1970 (ACT 350)

- Chieftaincy Under THE LAW - Ollenu J

- Ex Parte Bannerman - case