- Information

- AI Chat

Was this document helpful?

Bonsu v. Forson - A case

Course: Constitutional law of Ghana and its history (FLAW306)

346 Documents

Students shared 346 documents in this course

University: University of Ghana

Was this document helpful?

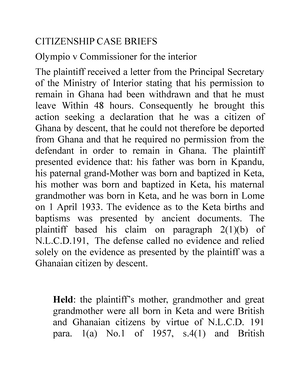

BONSU v. FORSON

[1964] GLR 45

Division: IN THE SUPREME COURT

Date: 27 JANUARY 1964

Before: SARKODEE-ADOO, OLLENNU AND BLAY JJ.S.C.

Defamation—Slander—Defamatory statement—Statement that “You are a thief, you are a hopeless

lawyer . . .”—Statement alleged to have been made in course of a quarrel—Whether defamatory or mere

vulgar abuse—Whether words understood as defamatory of the plaintiff—Duty of judge sitting as judge

and jury.

Evidence—Witnesses—Testimony of plaintiff and defendant—Both adjudged as truthful

witnesses—Evidence of defendant preferred—Whether court right in accepting defendant’s evidence in

preference to plaintiff’s.

HEADNOTES

The appellant instituted this action against the respondent at the High Court, Kumasi, for publishing

defamatory words about him. The respondent was alleged to have said that the appellant was a thief, a

hopeless lawyer who depended on one Owusu Afriyie, another lawyer, for his cases, and a hopeless M.P.

The respondent denied having spoken those words and contended that even if the words were spoken,

they could not be defamatory because of the circumstances in which they were spoken. The trial judge

held that the appellant had not sufficiently proved that the said words were spoken by the respondent. He

held further that even if it had been proved that the respondent spoke the words, since they were uttered in

the heat of a quarrel, they could not be said to be capable of defamatory meaning. On appeal, it was

argued for the appellant that since the trial judge found that the words used were prima facie defamatory,

he was wrong in holding that the appellant failed to prove that the hearers understood them to be

defamatory. It was also contended that since the trial judge found that both the plaintiff and the defendant

were truthful, he was wrong in preferring the evidence of the defendant to that of the plaintiff.

Held, dismissing the appeal:

(1) the trial judge was right in holding that the onus which lay on the appellant to prove that the words

were spoken by the respondent had not been discharged.

(2) Where a judge sits as a judge and jury, as a judge he has to decide as a prior question of law,

whether the words are capable of a defamatory meaning; if he should hold that they are, he must

proceed as a jury, to decide whether or not those words which are capable of a defamatory

[p.46] of [1964] GLR 45

meaning or which are prima facie defamatory were understood by the hearers as defamatory of the

plaintiff. In the particular circumstances, the trial judge was justified in holding that the alleged

words, even if spoken were uttered in the heat of passion and could not therefore be said to be

defamatory.

Students also viewed

Related documents

- An Analysis of the Kelson S Theory of La

- Peter Ankumah V. CITY Investment CO. LTD

- Attorney-General v Guardian Newspapers Ltd (No 2)

- Mensah v Mensah - It’s a case under constitutional law

- White paper on the report of the constitution review commission of inquiry ext en

- THE Office OF Special Prosecutor- Final