- Information

- AI Chat

Constitutional law of ghana-pt1-ch2

case

Course

Constitutional law of Ghana and its history (FLAW306)

346 Documents

Students shared 346 documents in this course

University

University of Ghana

Academic year: 2019/2020

Uploaded by:

Anonymous Student

This document has been uploaded by a student, just like you, who decided to remain anonymous.

University of GhanaRecommended for you

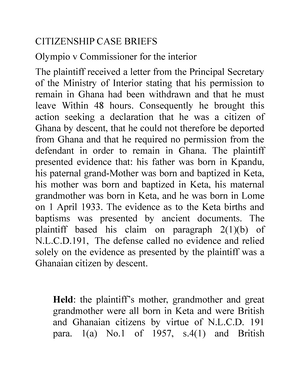

Preview text

© F A R Bennion Website: francisbennion

Doc. No. 1962.001 Butterworths, 1962

Any footnotes are shown at the bottom of each page

For full version of abbreviations click ‘Abbreviations’ on FB’s website

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF GHANA

Francis Bennion

PART I - THE REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION

CHAPTER 2

THE CREATION OF THE REPUBLIC

1. Legal Difficulties

Ghana was the first member of the Commonwealth to provide herself with a republican

Constitution without having had the means for doing so expressly indicated by United Kingdom

legislation. Both India and Pakistan, Ghana's precursors as Commonwealth republics, had been

provided with Constituent Assemblies by the Indian Independence Act, 1947. Burma is in a

different category, having become overnight a republic outside the Commonwealth by virtue of a

treaty made between the British Government and the Provisional Government of Burma and of the

provisions of the Burma Independence Act, 1947.* Since no Constituent Assembly had been

provided for by the Ghana Independence Act it became necessary to give careful consideration to

the means whereby a republican Constitution could be enacted. Not even the existence in the first

place of a Constituent Assembly with unchallengeable powers had saved Pakistan from acute

constitutional difficulties in trying to turn herself into a republic and it was felt that every care must

be taken to avoid the possibility of doubt arising as to the validity of Ghana's new Constitution. At

first it was assumed that the Constitution could be enacted by the Parliament of Ghana in the same

way as an ordinary Act. It would no doubt be desirable to avoid embodying the usual enacting

formula, with its reference to the Queen, in the Constitution itself but this could be done by the use

of a device such as the inclusion of the Constitution in a Schedule to the Act bringing it into force.

An examination of the provisions relating to the powers of the Parliament of Ghana however gave

rise to doubts as to whether it would be wise to follow this course.

The powers of the Parliament of Ghana derived from the First Schedule to the Ghana

Independence Act, 1957 and s. 31 of the Ghana (Constitution) Order in Council, 1957. The First

Schedule

1 See Halsbury's Laws (3rd Edn.), Vol. 5, p. 458.

74

CHAP. 2.—The Creation oj the Republic 75

contained six paragraphs. 1 The first three reproduced, with the same

wording apart from consequential alterations, ss. 2 and 3 of the Statute of

Westminster, 1931. By these it was provided that the Colonial Laws

Validity Act, 1865 2 would not apply to laws made by the Parliament of

Ghana, that such laws would not be inoperative on the grounds of

repugnancy to the law of England or any existing or future British Act, and

that the Parliament of Ghana had full power to repeal or amend British

legislation forming part of the law of Ghana and to make laws having

extraterritorial operation. The fourth and fifth paragraphs contained minor

consequential amendments to the Merchant Shipping Act, 1894 and the

Colonial Courts of Admiralty Act, 1890. The final paragraph withheld the

power to alter the 1957 Constitution otherwise than in the manner

specified in that Constitution. Section 31 of the 1957 Constitution stated:

" Subject to the provisions of this Order, it shall be lawful for

Parliament \sc. the Ghana Parliament constituted by the Order] to

make laws for the peace, order and good government of Ghana."

The Order contained several provisions expressly limiting the legislative

power. Section 31 (2) and (3) and s. 34 restricted the power to make laws

imposing disabilities on racial grounds, or depriving persons of freedom of

conscience or religion, or providing for compulsory acquisition of

property. Sections 32 and 33 restricted the power to make laws altering the

constitutional provisions, or changing regional boundaries, by requiring

such laws to be passed by a special procedure. It will be seen that,

whatever the political intention behind the enactment of these provisions,

they were in form somewhat removed from a clear grant of full legislative

sovereignty. The provisions of the First Schedule were mainly negative in

form while the legislative power conferred by the 1957 Constitution was

clearly limited. By using the special procedure laid down by ss. 32 and 33

of the 1957 Constitution the Ghana Parliament in 1958 removed those very

sections from the Constitution, and also repealed paragraph 6 of the First

Schedule to the Ghana Independence Act. 3 The other restrictions

remained, although there is a strong argument for

1 See Appendix A, p. 467, post.

2 See p. 18, ante.

3 See p. 69, ante.

CHAP. 2.—The Creation of the Republic 77

England, or to the provisions of any existing or future Act of the

Parliament of the United Kingdom."

This follows precisely the wording of paragraph 1 (2) of the First

Schedule to the Ceylon Independence Act, 1947, which in turn was derived

from s. 2(2) of the Statute of Westminster, 1931. Doubt exists as to

whether the reference to any existing or future Act includes a reference to

the Act in which it appears. It is tempting to say that there is no receptacle

between the present and the future which, at the moment when an Act

comes into operation, is large enough to accommodate the Act. The Act at

this moment must either be an existing Act, because it has just come into

existence, or (if it has not just come into existence) it must be future Act.

This reasoning was not followed by the British Parliament when it enacted

the Indian Independence Act, 1947, s. 6(2) of which prevents any law

made by the legislature of either of the new Dominions created by that Act

from being invalid on the ground that it is repugnant to " this or any

existing or future Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom ". This

difference in the wording of the two Independence Acts of 1947 gave rise

to considerable comment, though the general view seems to have been t hat

it did not indicate a difference in substance. Thus Professor K. C. Wheare

said:

" In the Ceylon Act, as in the Statute of Westminster, the powers

conferred relate to ' any existing or future Act of Parliament '. This

raises a controversy. Does the difference in wording amount to

anything? Does it mean that Ceylon cannot amend its Independence

Act, just as, it has been maintained, the Dominions cannot amend the

Statute of Westminster? Is the Independence Act or the Statute an '

existing ' Act of Parliament? If it is—and the case for this view seems

sound— why was it thought necessary to include ' this ' in the Indian

Independence Act? If, ' this ' was put in to resolve doubts for India

and Pakistan, why was it not done for Ceylon also? Is some limitation

intended upon Ceylon's legislative competence? These questions have

aroused some discussion in Ceylon. It may not console the people of

Ceylon to know that the difference is probably due to nothing more

than a difference of draftsmen." 1

Again, Geoffrey Marshall finds the distinction " insignificant '' and goes

on to remark that nothing in the legislative intention of the United

Kingdom Parliament seems to justify the conclusion that the

Parliament of Ceylon is unable to legislate

1 Journal of Comparative Legislation, 3rd Series, Vol. XXX, p. 80.

78 PART I.—The Republican Constitution

repugnantly to, or to amend, the Ceylon Independence Act. 1 Despite these

doubts the United Kingdom Parliament enacted the " repugnancy "

provisions for Ghana in exactly the same terms as for Ceylon. This may be

taken to indicate that Parliament thought the doubts so trivial as to be

beneath notice or that it wished to indicate that there was a difference of

substance between the Indian and Ceylon provisions. Either view is

possible, but the former seems more likely to be correct. It had indeed been

already acted on in Ghana, the Constitution (Repeal of Restrictions) Act,

1958 (No. 38) having repealed paragraph 6 of the First Schedule to the

Ghana Independence Act. 2

In the light of these difficulties there seemed to be three different

methods of procedure open. These were:

1. To disregard the doubts and proceed to pass the republican

Constitution as an ordinary Act of Parliament.

2. To pass an Act of Parliament under the procedure laid down by s.

1 (1) (a) of the Ghana Independence Act by which the Parliament of

Ghana requested and consented to the enactment by the Parliament of the

United Kingdom of an Act confirming that the Parliament of Ghana had

since its inception possessed full legislative power, including power to

withdraw Ghana from Her Majesty's Dominions and to remove the

Queen as an organ of Parliament.

3. To make the new Constitution " autochthonous " by basing it

firmly on the will of the people. This could be done by the holding of a

referendum on the instructions of the Cabinet and the subsequent

enactment by the National Assembly, as a Constituent Assembly

deriving its authority from the verdict of the people in the referendum, of

the new Constitution. 3

The second course was ruled out on political grounds. The third was felt

to involve too great a danger of matters getting out of control: the

referendum would not be conducted under the authority of any Act, and it

might not therefore be possible to

1 Parliamentary Sovereignty and the Commonwealth, Oxford, 1957, p. 126.

2 The wording was changed in the Nigeria Independence Act, 1960, to

read: "... repugnant to the law of England, or to the provisions of any

Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, including this Act

(Sch. I, para. 2). 3

On the question of autochthony see Wheare, Constitutional Structure of

the Commonwealth, Chap. IV; Robinson, Constitutional Autochthony in

Ghana, the Journal of Commonwealth Political Studies, 41.

80 PART I.—The Republican Constitution

time available for the preparation of the Constitution, they were rendered of

small account by the prevailing political conditions. There might be much

dispute in Ghana as to the form a new Constitution should take, but there

was a unanimous view that Ghanaians were since independence free to

choose their own form of government. 1 Nor was any dissenting voice to be

heard from the United Kingdom, where the authorities were sympathetic to

Ghana's aspirations and ready to assist their fruition. The political realities

were overwhelmingly in favour of brushing aside legalistic doubts and

pursuing a straightforward course. In the end the course actually followed

was a combination of the first and third procedures mentioned above.

2. THE CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY AND PLEBISCITE ACT

Under the 1957 Constitution the constitutional conventions attaching to

the British Crown were expressly applied to Ghana. 2 Whether or not these

conventions can be said to include the doctrine that fundamental legislation

should not be enacted without a " mandate " from the electorate, this

doctrine was in fact recognized as valid in Ghana. Sir Ivor Jennings has

pointed out that the doctrine is not limited to the United Kingdom:

" President de Valera declared in 1932 that the Dail could not deal

with the question of separation from the British Commonwealth of

Nations because, though his Government had a mandate for removing

the oath from the Constitution and for suspending the payment of the

land annuities, it had no mandate to create a republic." 3

The Ghana Government had no mandate at the beginning of 1960 to

create a republic, and readily acknowledged the fact. As Mr. Ofori Atta, the

Minister of Local Government, put it in the National Assembly:

1 Speaking in the debate on the draft republican Constitution, Mr. J. A

Braimah, who had transferred from the United Party to the C.P., said:

" In rising to make my humble contribution to this debate, my mind

automatically goes back to the Atlantic Declaration of August, 1941,

which stated among other things that the signatories ' respect the right of

all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live '.

In the exercise of this undoubted right, Ghana has therefore decided to

choose the form of government under which her people will live and no

one, in or outside this country, can quarrel with that desire." (Proceedings

of the Constituent Assembly, 2 19.)

3 By s. 4 (2).

The Law and the Constitution (4th Edn.), p. 165.

CHAP. 2.—The Creation of the Republic 81

" The present Members of Parliament were however not elected by

the people for the purpose of enacting a republican constitution and

the question of a republic was not an issue at the last general election.

At that election, of course, certain constitutional principles were

settled. The people voted for a unitary form of government and

rejected a federal form of government. Nevertheless, it cannot be said

that this House, as at present constituted, has a mandate from the

people to adopt or make on their behalf, any particular form of

republican constitution." 1

The Government decided to seek a mandate, and took the view that the

people should be asked to vote not merely on the simple question of

whether Ghana should become a republic or not, but also on the broad

principles to be adopted in framing the new Constitution. It was also

thought desirable, assuming the people would support a change to

republican status, to find a means of enabling them to choose the person

they wanted as the new head of state. Furthermore there was the question

on whom the mandate to enact a new Constitution was to be conferred.

The United Party, who constituted the official Opposition, took the view

that there should be a Constituent Assembly which would be

"... an entirely new body elected and appointed freely to represent all

the interests of the country, i. the Members of Parliament, Chiefs,

the University Colleges (Legon and Kumasi), the Churches, the

Muslim Council, the Professional Associations, the Chambers of

Commerce, the Farmers' Unions, the T.U., the Co-operative

Societies, the Ex-servicemen's Organisations, the Ghana Women's

Federation or Council and the political parties." 2

However, in the Government's opinion, which prevailed, the existing

Members of Parliament themselves were best fitted to form the

Constituent Assembly:

" They were chosen by the people at the last general election to

represent them in making laws for Ghana and it is therefore right that

Members of Parliament and not other persons who have not been so

chosen should constitute the Constituent Assembly." 3

The Constituent Assembly and Plebiscite Bill was accordingly

introduced into the National Assembly on 23rd February, 1960. Of the two

main clauses, which were not altered during the passage

1 Pari. Deb. Official Report, Vol. 18, col. 7 (23rd February, 1960).

2 Pari. Deb. Official Report, Vol. 18, col. 46.

3 Ibid., col. 7 (speech of Mr. Ofori Atta).

D

CHAP. 2.—The Creation of the Republic 83

also served to indicate that the powers of the Constituent Assembly were

not limited to enacting a Constitution, as indeed was shown by the words "

or in connection with " in the opening passage of clause 2. If the powers

had been so limited, argument might have arisen as to what provisions

were within the scope of a Constitution and in any case it was already the

intention of the Government to introduce a number of other Bills of a

constitutional nature apart from the Constitution itself.

Clause 2 went on to provide that the existing law governing the National

Assembly (except s. 42 of the 1957 Constitution) should apply with any

necessary modifications to the Constituent Assembly, and that " subject to

the provisions of any enactment made by the Constituent Assembly "—a

reference to the new Constitution, which would abolish the legal existence

of the old National Assembly—nothing in the Bill was to affect the

working of the National Assembly as such.

Clause 3 enabled a constitutional plebiscite to be held:

" In order, before passing a Bill for a new Constitution, to inform

itself as to the wishes of the people on the form of the Constitution, or

the person who is to become the new Head of the State or any other

matter, the Constituent Assembly may order the holding of a

plebiscite to determine such questions as the Constituent Assembly

may direct."

Although power to hold a referendum already existed under the

Referendum Act, 1959 (No. 10), it was felt that this should not be used for

testing opinion on the republican issue. Under that Act the referendum

would have had to be ordered by the Governor-General, whereas it seemed

more appropriate, since the task of constitution-making was entrusted to

the Constituent Assembly, to place control over the questions to be asked

and other relevant matters in the hands of that body. Although the two

main questions had already been chosen in principle by the Government,

clause 3 allowed other questions to be put if it was later thought necessary

to do so. This power did not in fact have to be used.

Clause 3 went on to give the Constituent Assembly power to make

regulations governing the detailed procedure of the plebiscite. In view of

recent by-election disturbances, this power was made sufficiently wide to

enable public order to be maintained by the control of the movement and

assembly of persons and the supply of intoxicating liquor. Power to

provide for requisitioning of vehicles and buildings was also given.

84 PART I.—The Republican Constitution

Clause 4 of the Bill, which was the only one to be amended,

dealt with its duration. As introduced, this provided that the

Act was to be automatically repealed on the coming into

operation of a Constitution enacted by the Constituent

Assembly. It was amended so as to delete this repeal while

taking away the right of the National Assembly to resolve

itself into a Constituent Assembly once the new Constitution

had come into force. One reason for the change was a

technical one connected with the passing of a new

Interpretation Act. The other was to enable the measure to

remain on the statute book " so as to explain how Acts were

enacted by the Constituent Assembly."

1

In view of the fact

that the repeal of an Act does not affect its previous operation

or anything done under it 2 no harm would be caused by

repeal, although the Act may perhaps be allowed to remain as

a historical document.

While the United Party criticised the Constituent Assembly

and Plebiscite Bill on points of detail they did not press their

opposition to a division at any stage. The Bill was passed on

25th February, 1960, received the Royal Assent the same day

and came into operation on its publication as a supplement to

the Ghana Gazette two days later. 3

So that the Constituent Assembly should not find itself in

procedural difficulties at its first meeting, the National

Assembly passed a special motion on 29th February. This

provided that the Standing Orders of the National Assembly

were to apply for the purposes of the Constituent Assembly

subject to certain modifications. On any day appointed for the

transaction of business by the Constituent Assembly, the

Speaker was required, at the conclusion of National Assembly

business, to put the question " That this House do now resolve

itself into a Constituent Assembly ", which was to be decided

without amendment or debate. At the end of Constituent

Assembly business the National Assembly was automatically

to resume. The Speaker was enabled to take the chair at the

Committee stage of Bills, and minor adjustments were made

to the procedure for the passing of Bills. 4

1 See Pari. Deb. Official Report, Vol. 19, cols. 11 and 61

2 Interpretation Act, 1960 (C. 4), s. 8.

3 The text of the Constituent Assembly and Plebiscite Act is given in

Appendix A, p. 470, 4 post.

Minutes of the National Assembly, 29th February, 1960. The motion

was later amended to allow Bills to be introduced before the prescribed

period had elapsed after publication: Minutes of the National Assembly

7th June, 1960.

86 PART I.—The Republican Constitution

2. That the Head of State and holder of the executive power should

be an elected President responsible to the people.

3. That Parliament should be the sovereign legislature and should

consist of the President and the National Assembly, and that the

President should have a power to veto legislation and to dissolve

Parliament.

4. That a President should be elected whenever there is a general

election by a method which insures that he will normally be the leader

of the party which is successful in the general election.

5. That there should be a Cabinet appointed by the President from

among Members of Parliament to assist the President in the exercise of

his executive functions.

6. That the system of courts and the security of tenure of judges

should continue on present lines.

7. That the control of the armed forces and the civil service should

be vested in the President." 1

It was explained that these seven points constituted the essence of the

Government's proposals. The Government would not consider itself bound

to introduce a Constitution Bill which followed word for word the draft in

the White Paper, since, in the light of reactions to the draft, changes of

detail, arrangement and emphasis might be found desirable. However, if

the people approved the proposals, the seven points would be treated as

fundamental.

The constitutional proposals were received with keen interest by the

world press. British comment was on the whole favourable. The Times

expressed the view that:

" It is an ingenious constitution, avowedly aimed at efficient

government during the early stages of development and expertly

framed to suit Ghanaian conditions." 2

The Daily Mirror, under the heading " Good Luck Ghana! ", said:

" The new Constitution puts paid to any idea that Ghana is heading

for dictatorship." 3

The Manchester Guardian found that:

" Altogether, the draft Constitution seems quite a promising one,

and there is no reason why Ghana should not remain a welcome

member of the Commonwealth under it." 4

1 W. P. No. 1/60, p. 16.

2 Issue of 7th March, 1960.

3 Issue of 7th March, 1960.

4 Issue of 7th March. 1960.

CHAP. 2.—The Creation of the Republic 87

The Irish Independent said of the proposal to couple the election of the

President with that of Members of Parliament:

" This is an arrangement without precedent and, on paper, is full of

promise. It combines strong government with democracy, something

which older countries have often failed to achieve." 1

In the United States the draft Constitution was generally welcomed as

marking the final emancipation of Ghana from colonial rule. The

Washington Post commented:

" What makes the move of special significance is that Ghana, as

the first West African country to attain full independence from

colonial status in 1957, is in many respects the bellwether for the

continent during an exciting period." 2

On the other hand the reception in South Africa was generally cool. The

Natal Witness referred to " Black Bonapartism ", while the Pretoria News

found the proposals a serious departure from British democratic principles.

In France, L'Information described the draft Constitution as at the same

time authoritarian and expansionist. All over the world, whatever the

attitude adopted, great interest was shown and the press devoted much

space to describing and examining in detail the blue-print for Ghana's

republican future.

In Ghana itself the press reaction was predictable. The Ghana Times

and the Evening News, both strong Government supporters, gave the

proposals an enthusiastic welcome. The British-owned Daily Graphic

printed the entire draft Constitution and advised those who liked the draft

to accept it and those who disliked it to reject it. The Ashanti Pioneer, at

that time an Opposition newspaper, was outspokenly critical.

The first sitting of the Constituent Assembly took place on 14th March,

1960. The Prime Minister, Dr. Nkrumah, moved

" That the Constituent Assembly recommends to the people of

Ghana the Government proposals for a republican Constitution set

out in the White Paper issued on the 7th March, 1960."

His opening words were:

" It is with joy and pride that I appear this morning, before the

representatives of the people of the nation of Ghana here gathered in a

Constituent Assembly, to move this motion. I do so with thankfulness

to the dead and the living, who by their sweat, blood and sacrifice

have made possible the victory of

1 Issue of 26th March, 1960.

2 Issue of 22ud March, 1960.

CHAP. 2.—The Creation of the Republic 89

the holding of the plebiscite. 1 Voting was to take place in

specified parts of Ghana on three different days so that the

limited numbers of polling staff and police available could be

moved from one place to another. Provision was included for

the dates to be changed by Gazette notice if necessary, and in

fact this had to be done. 2 The order provided for nominations

for the office of Head of State under the new Constitution.

The candidate had to be a citizen of Ghana who had attained

the age of thirty-five, and the nomination form had to be

signed by not less than ten Members of Parliament. As the

names of the candidates could not definitely be known until

the period for nominations had elapsed (it was thought that

the Opposition might boycott the plebiscite), the order left the

actual questions to be determined at a future time. The

candidates nominated were Dr. Nkrumah and Dr. J. B.

Danquah, the doyen of the United Party. 3 When the closing

date for nominations had passed, the Constituent Assembly

made a further order directing two questions to be submitted

for the determination of the voters. 4 These were:

"1. Do you accept the draft republican Constitution for

Ghana as set out in the White Paper issued by the

Government on 7th March, 1960?

2. Do you accept Kwame Nkrumah or Joseph Boakye

Danquah as the first President under the new

Constitution? "

The White Paper had stated that the Government would

propose to the Constituent Assembly that voting should be

on a parliamentary constituency basis, so that the people of

Ghana would know not only the total number of votes cast

but also the state of opinion in each constituency. 6 This was

accordingly provided for in the detailed regulations made by

the Assembly to govern voting procedure. 6 The regulations

closely followed those in force for general elections. Both

the Opposition and Government parties were entitled to have

polling agents present in every polling station as a check

against irregularities, and also to have a counting agent in

each constituency to witness the counting of votes. There

were four ballot boxes in each polling station, and the voter

was given two papers. One was to be put either in the

1 Constitutional Plebiscite Order, 1960 (E. 73).

2 Ghana Gazette, 30th March, 1960.

3 Ghana Gazette, 21st March, 1960.

1 Constitutional Plebiscite (Questions) Order, 1960 (E. 75).

6 W. No. 1/60, p. 7.

6 Constitutional Plebiscite Regulations. 1960 (E. 74).

####### [f

90 PART I.—The Republican Constitution

box bearing the word " yes " in white on a red ground or the

box bearing the word " no " in black on a white ground, indi-

cating approval or disapproval of the draft Constitution. The

other was to be put either in the box bearing the photograph

of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah and the red cockerel symbol of the

C.P. or in the box bearing the photograph of Dr. J. B.

Danquah and the cocoa-tree symbol of the United Party. 1

Apart from answering the two questions posed, the votes were

to serve an additional purpose. The Government had pointed

out that the plebiscite would correspond very nearly to a

general election. The Presidential candidates were the

respective leaders of the only two political parties in the

country, and voting was on a constituency basis. It would thus

be possible to tell in which constituencies the Government

and the Opposition had a majority. The Government had

accordingly announced that if the Presidential election

showed that there would be little change in the balance of

parties in the Assembly if a further general election were held,

they would treat this as a mandate to extend the life of the

existing Assembly, which was due to be dissolved by July,

1961 at the latest. 2

The public were informed of the holding of the plebiscite,

the issues involved and the method of voting in a number of

ways. Apart from the issue of the White Paper and the

widespread newspaper coverage, a large number of posters

were put up all over the country. Among these were posters

setting out the seven points listed in the White Paper. The

posters were printed in English and in nine of the vernacular

languages, including Twi, Fante, Ga and Ewe.

The plebiscite was held on 19th, 23rd and 27th April, 1960,

and proved a triumph for the Government. Dr. Nkrumah was

elected as first President in all but two of the 104

constituencies, obtaining 1,015,740 votes as against 124,

cast for Dr. Danquah. Only in one constituency was there a

majority against the draft Constitution, which was approved

by 1,009,692 votes to 131,393. 3 The great interest aroused

was indicated by the fact that more than half the registered

electors voted. 4

1 Constitutional Plebiscite (Symbol) Regulations, 1960 (E I 76)

2 W. No. 1/60, p. 11.

3 Ghana Gazette, 14th May, 1960.

4 The exact proportion was calculated at 54%. Surprisingly, in view

of its high illiteracy rate, the biggest proportion was in Ashanti, where 76 "/

of the registered electors voted.

°

92 PART I.—The Republican Constitution

That no person should be deprived of his property save where the

public interest so requires and the law so provides. 1

Following a suggestion made by Government backbenchers, 2 the position

of the Chief Justice was altered to enable him to be dismissed at will from

his office of Chief Justice, though not from his judgeship. 3 As the

Memorandum explained, the new version

" assimilates the position of the Chief Justice to that of Lord

Chancellor in England. The Chief Justice must be a Judge of the

Supreme Court, and cannot be removed from his judgeship. 4 He may,

however, be removed as Chief Justice if the President thinks fit. His

capacity as Chief Justice makes him the administrative head of the

Judicial Service, and in relation to such non-judicial functions it is

considered that the President ought to be in a position to ensure that

the Chief Justice will give his loyal co-operation."

Criticism had been aroused by a provision in the first draft which gave

the President unfettered discretion to grant loans from public funds. This

was met by giving the National Assembly power to require any agreement

for a loan to be submitted for their ratification. 5 The opportunity was also

taken to entrench the article charging the public debt on the general

revenues and assets of Ghana. 6 The criticism that the Attorney-General

appeared to be given power by the first draft to discontinue civil

proceedings brought against the Republic was met by an amendment

making it clear that this was not so.' Other changes that should be

mentioned here were as follows. The article listing the laws of Ghana was

completely altered. 8 The system of courts was

1 Article 13 (1).

2 See p. 88, ante.

3 Article 44 (3).

4 I., without a vote of two-thirds of the members of the National

Assembly. 6

6 Article 35 (2).

Article 37 (2).

' Article 47 (2). 8

Article 40. The original version stated that the laws comprised:

" (a) indigenous laws and customs not being repugnant to natural justice,

equity and good conscience, in so far as their applica tion is not

inconsistent with any enactment for the time being in force, and

(b) the doctrines of common law and equity, in so far as their application

is not inconsistent with such indigenous laws and customs or with any

enactment for the time being in force, and

(c) enactments for the time being in force made under powers conferred

by the Constitution or previously existing."

CHAP. 2.—The Creation of the Republic 93

modified—instead of a Supreme Court functioning both as a

Court of Appeal and a High Court, two separate superior

courts were established, namely the Supreme Court and the

High Court. 1 The Supreme Court was made the final court of

appeal and also given an exclusive original jurisdiction over

questions as to the validity of legislation. 2 The section

dealing with the Civil Service was widened to cover the

Public Services generally. 3 In consequence the article

establishing the Civil Service Commission was omitted, and

mention was made of the police. To emphasize its civilian

character, in the words of the Memorandum, the description

of the police was changed from Police Force to Police

Service.

Before the second reading of the Constitution Bill, which

took place on the day it was introduced, the Constituent

Assembly passed a procedural motion governing the

Constitution Bill and all other Bills to be passed by the

Constituent Assembly. This was necessary because the

Ordinances Authentication Ordinance (Cap. 2) had been

disapplied by s. 2(3) of the Constituent Assembly and

Plebiscite Act, 1960 (No. 1). Provision had therefore to be

made for such matters as the authentication, numbering and

publication of Acts of the Constituent Assembly. 4 The

motion was on similar lines to those subsequently laid down

for Republican Acts by the Acts of Parliament Act, 1960

(C. 7).

The second reading debate passed off quietly. The results

of the plebiscite left the Opposition little scope for objection

to the Bill and they were in any case appeased to some extent

by the fact that alterations had been made in the Bill to meet

their criticisms. Mr. Dombo, the Leader of the Opposition,

remarked:

" I think most of the criticisms we levelled against this

Constitution have been met and for that reason I say well

done to the people who have redrafted it." 6

He continued to find objectionable however the statement in

art. 8(4) that the President is not obliged to follow advice

tendered by any other person. This had been widely

criticized as contravening the customary principle that a

chief, though by forms and ceremonies appearing autocratic,

was in reality bound

1 Article 41.

2 Article 42 (2).

3 Part VIII.

4 The text of the motion is given in Proceedings oflhe Constituent A ssembly,

161.

5 Proceedings of the Constituent Assembly, 178.

Was this document helpful?

Constitutional law of ghana-pt1-ch2

Course: Constitutional law of Ghana and its history (FLAW306)

346 Documents

Students shared 346 documents in this course

University: University of Ghana

Was this document helpful?

© F A R Bennion Website: www.francisbennion.com

Doc. No. 1962.001.074 Butterworths, 1962

Any footnotes are shown at the bottom of each page

For full version of abbreviations click ‘Abbreviations’ on FB’s website

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF GHANA

Francis Bennion

PART I - THE REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION

CHAPTER 2

THE CREATION OF THE REPUBLIC

1. Legal Difficulties

Ghana was the first member of the Commonwealth to provide herself with a republican

Constitution without having had the means for doing so expressly indicated by United Kingdom

legislation. Both India and Pakistan, Ghana's precursors as Commonwealth republics, had been

provided with Constituent Assemblies by the Indian Independence Act, 1947. Burma is in a

different category, having become overnight a republic outside the Commonwealth by virtue of a

treaty made between the British Government and the Provisional Government of Burma and of the

provisions of the Burma Independence Act, 1947.* Since no Constituent Assembly had been

provided for by the Ghana Independence Act it became necessary to give careful consideration to

the means whereby a republican Constitution could be enacted. Not even the existence in the first

place of a Constituent Assembly with unchallengeable powers had saved Pakistan from acute

constitutional difficulties in trying to turn herself into a republic and it was felt that every care must

be taken to avoid the possibility of doubt arising as to the validity of Ghana's new Constitution. At

first it was assumed that the Constitution could be enacted by the Parliament of Ghana in the same

way as an ordinary Act. It would no doubt be desirable to avoid embodying the usual enacting

formula, with its reference to the Queen, in the Constitution itself but this could be done by the use

of a device such as the inclusion of the Constitution in a Schedule to the Act bringing it into force.

An examination of the provisions relating to the powers of the Parliament of Ghana however gave

rise to doubts as to whether it would be wise to follow this course.

The powers of the Parliament of Ghana derived from the First Schedule to the Ghana

Independence Act, 1957 and s. 31 of the Ghana (Constitution) Order in Council, 1957. The First

Schedule

1 See Halsbury's Laws (3rd Edn.), Vol. 5, p. 458.

74

Too long to read on your phone? Save to read later on your computer

Discover more from:

- Discover more from: