- Information

- AI Chat

Ex Parte Bannerman - case

Constitutional law of Ghana and its history (FLAW306)

University of Ghana

Recommended for you

Students also viewed

- Judgment PS Investment V Ceredec & ORS-1

- Standard BANK Offshore Trust COMP. LT. VRS National Investment BANK & 2 ORS

- An Analysis of the Kelson S Theory of La

- Peter Ankumah V. CITY Investment CO. LTD

- Yakubu Awbego Vrs. Tindana Agongo Akubayela ; Immovable property – Allodial title to land, ownership of land, traditional evidence, resolution of conflicts arising from traditional evidence

- Attorney-General v Guardian Newspapers Ltd (No 2)

Related Studylists

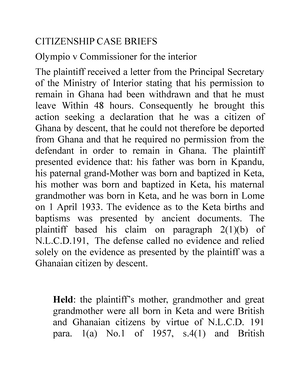

Constitutional Law CasesPreview text

REPUBLIC v. STATE FISHING CORPORATION COMMISSION OF ENQUIRY (CHAIRMAN); EX PARTE BANNERMAN

[1967] GLR 536

Division: HIGH COURT, ACCRA

Date: 20 JULY 1967

Before: EDUSEI J.

Administrative law—Commission of inquiry—Jurisdiction—Terms of reference of commission not extending to suspending from office witnesses appearing before it—Whether commission acted ultra vires in writing letter of suspension—Commission of Enquiry (State Fishing Corporation) Instrument, 1967 (E. 6), para. 3.

Natural justice—Right to be heard—Extent of rule—Whether confined to strictly legal tribunals or applicable to every authority adjudicating upon matters involving civil consequences to individuals.

State proceedings—Certiorari—Executive discretion—Purported dismissal of applicant by N.L. ultra vires enabling instrument—Applicant not given right to be heard—Whether in circumstances certiorari could issue—State Fishing Corporation Instrument, 1965 (L. 397), Pt.

HEADNOTES

In January 1967, the National Liberation Council (N.L.) in the exercise of the powers conferred on it by the Commission of Enquiry Act, 1964 (Act 250), s. 1 appointed a commission of enquiry to inquire into the management and other matters relating to the State Fishing Corporation. The terms of reference of the commission were contained in E. 6 of 1967, para. 3. During the April sittings of the commission of inquiry certain allegations of larceny were made against the applicant, the distribution marketing manager of the corporation. On 26 June 1967 the chairman of the commission of inquiry wrote to the applicant relieving him of his duties and responsibilities and a copy of this letter (exhibit B) was sent to the office of the N .L. The suspension was later confirmed by a letter (exhibit 2) from the office of the N.L. The applicant instituted proceedings for orders for certiorari to quash the decision of the commission of inquiry and prohibition to prevent the chairman of the commission from suspending, dismissing, interdicting or in any manner interfering with the applicant in the performance of his duties as

distribution marketing manager of the State Fishing Corporation on the grounds that: (1) the executive instrument which set up the commission conferred no jurisdiction upon it to interfere in any way with the service contract of the applicant; (2) the suspension letter was a speaking order and therefore bad in law; and (3) there was a breach of the rules of natural justice.

Counsel for the respondent conceded these three grounds, but did not agree that the letter was a speaking order since it did not contain any reason for the suspension. He argued that at its worst what the chairman of the commission did was something of a n administrative nature and a writ of certiorari would not lie. He however asked the court to consider the letter from the office of the N.L.

[p] of [1967] GLR 536

Held:

(1) the commission or its chairman in suspending the applicant did not act administratively; it rather acted in excess of its jurisdiction having regard to its terms of reference as contained in E. 6 of 1967 and there could be no doubt that on this ground certiorari should issue to quash the decision contained in exhibit B.

(2) Even if the commission or its chairman had had the power to suspend the applicant, in the circumstances, its exercise would have been deemed capricious. Whether the chairman was acting administratively or judicially in suspending the applicant he was still subject to the rules of natural justice, and in particular to the audi alteram partes rules. This rule was not confined to the conduct of strictly legal tribunals but was applicable to every tribunal or body of persons invested with authority to adjudicate upon matters involving civil consequences to individuals. Spackman v. Plumstead District Board of Works (1885) 10 App. 229, H.;R v. Cambridge University (1723) 1 Stra. 557; Wood v. Woad (1874) L. 9 Exch. 190 and dicta of Lord Hodson in Ridge v. Baldwin [1964] A. 40 at p. 130, H. applied.

Obiter. Part XIV of L. 397 dealt with the special powers of the President (now N.L.). This stated among other things that the N.L. might at any time, if satisfied that it was in the national interest to do so, take over the control and management of the affairs or any part of the affairs of the corporation and might for that purpose (a) reconstitute the board, and (b) appoint, transfer, suspend or dismiss any of the employees. The assumption of control and ma nagement of the corporation by the N.L. was a condition precedent to the exercise of those powers. In the absence of any such evidence, the purported suspension of the applicant was ultra vires the N.L. It was also contrary to natural justice, the applicant not having been heard and could be questioned by the courts by a writ of certiorari. Ridge v. Baldwin (supra) and dicta of Lyndhurst C. in Capel v. Child (1832)2 C. & J. 558 at p cited.

CASES REFERRED TO

in paragraph 3 of the Commission of Enquiry (State Fishing Corporation) Instrument, 1967 (E. 6).

The respondent in the instant application is the chairman of the commission of inquiry, and the applicant is the distribution marketing manager of the State Fishing Corporation.

The commission entered upon its duty as set out in its terms of reference and its sittings so far covered the period from 10 February 1967 to 28 June 1967. On 26 June 1967 the chairman of the Commission of Enquiry (State Fishing Corporation) purported to suspend Mr. V. Bannerman, the distribution marketing manager of the State Fishing Corporation. The letter of the purported suspension emanated from the office of the Commission of Enquiry (State Fishing Corporation) Accra and it was signed by Mr. S. A. Wiredu, the chairman of the commission of inquiry. The letter, which is exhibit E, is as follows:

“Our Ref. No/CH/PERS/14.

OFFICE OF THE COMMISSION OF ENQUIRY,

(STATE FISHING CORPORATION)

P. O. BOX M.

ACCRA.

[p] of [1967] GLR 536

Dear Sir,

SUSPENSION

With immediate effect you are being relieved of your duties and responsibilities as distribution marketing manager in the State Fishing Corporation.

(2) You are to hand over immediately to your most senior subordinate and advise the chief accountant and the production manager.

Yours faithfully,

(Sgd.) S. A. WIREDU

(Chairman).

Mr. V. Bannerman,

Distribution Marketing Manager,

State Fishing Corporation,

TEMA.”

Copies of this letter were sent to the Secretary of the National Liberation Council and others.

The receipt of exhibit B by the applicant gave rise to the initiation of the instant proceedings for writs of (a) certiorari to quash the decision as contained in exhibit B, a nd of (b) prohibition to prevent the chairman or the commission from suspending, dismissing, interdicting or in any such manner interfering with the said V. Bannerman in the performance of his duties as distribution marketing manager of the State Fishing Corporation.

The applicant sought these two reliefs on the following grounds:

“(1) E. 6 of 1967 under which the Commission of Enquiry (State Fishing Corporation) was appointed confers no jurisdiction upon the commission of inquiry or the chairman to suspend, dismiss, interdict or otherwise interfere with the service contract of the applicant.

(2) That the said order contained in the letter dated 26 June 1967 being a ‘speaking order’ is bad in law in that the commission of inquiry or the chairman of the said commission can in no way whatsoever be regarded as the employer of the applicant for the purpose of enforcing any terms of service between the corporation and the applicant.

(3) Breach of the rules of natural justice in that the commission of inquir y did not summon the applicant to appear before it to justify his continued employment by the corporation.”

[p] of [1967] GLR 536

Mr. S. M. Boison, chief state attorney and counsel for the respondent, quite frankly and honestly conceded the three grounds just enumerated as the basis for the reliefs sought, except that he did not agree to the letter exhibit B being referred to as a speaking order on the ground that it did not contain any reason for the suspension. His contention in this regard appears to be well- founded, for in The Dictionary of English Law by Earl Jowitt and Clifford Walsh appears the following definition of a speaking order at Vol. 2, p, “an order containing a statement of what has led to the decision of the court... (R. v. Northumberland Compensation Appeal Tribunal [1952] 1 K. 338).” It is to be observed, however, that “court” in these circumstances is not to be construed as court stricto sensu, i. as a court of justice. “Court” in so far as reviews by means of the prerogative writs are concerned includes any person or body of persons to whom has been entrusted a “judicial” or “quasi-judicial” power of imposing obligations upon others. Thus Atkin L. expressed this in very eloquent language when he said:

“Wherever any body of persons having legal authority to determine questions affecting the rights of subjects , and having the duty to act judicially, act in excess of their legal authority they are subject to the controlling jurisdiction of the King’s Bench Division exercised in these writs.”

see how the chairman, in writing exhibit B, could be said to be acting administratively when his administrative functions are clearly and explicitly set out in section 6 of the Commission of Enquiry Act, 1964.

There can be no doubt in my mind that the writing of exhibit B was actuated by the revelation at the commission of inquiry on 7 April 1967 which charges the applicant and one Quaye with the larceny of some 1,100 cartons of fish; there were other unwholesome or deprecatory allegations made against the applicant by Moses on 10 April 1967. I cannot find any reason for the act of the chairman of the Commission of Enquiry (State Fishing Corporation) in suspending the applicant other than the cumulative effect of those allegations laid at his door at the commission of enquiry. In any case the chairman in deciding to suspend the applicant must have

[p] of [1967] GLR 536

been in possession of certain facts which rendered his suspension desirable in his opinion in the circumstances. If this was so it was imperative for the commission or its chairman to adhere to the very elementary principle of affording the applicant the opportunity to defend himself before condemning him. If even the chairman was acting administratively in suspending the applicant, it was incumbent upon him to adhere to the content of natural justice as ably expounded by Lord Selborne in Spackman v. Plumstead District Board of Works (1885) 10 App 229 at p. 240, H.:

“No doubt, in the absence of special provisions as to how the person who is to decide is to proceed, the law will imply no more than that the substantial requirements of justice shall not be violated. He is not a judge in the proper sense of the word; but he must give the parties an opportunity of being heard before him and stating their case and their view. He must give notice when he will proceed with the matter, and he must act honestly and impartially and not under the dictation of some other person or persons to whom the authority is not given by law. There must be no malversation of any kind. There would be no decision within the meaning of the statute if there were anything of that sort done contrary to the essence of justice.”

This principle of natural justice is usually referred to as the audi alteram partes rule, and, “even God himself did not pass sentence upon Adam, before he was called upon to make his defence. Adam (says God) where art thou? Hast thou not eaten of the tree whereof I commanded thee that thou shouldst not eat?” The statement was made in R. v. University of Cambridge (1723) 1 Stra at p. 567 when the courts came to the aid of Dr. Bentley and granted a peremptory mandamus to restore him to his degrees. Though the court was critical of Dr. Bentley’s behaviour, they considered that even if he had been guilty of a contempt to the Vice-Chancellor’s Court, that court had no power to deprive him of his degrees, but they held that in any event he could not be deprived without notice.

Again in Wood v. Woad (1874) L. 9 Exch. 190 at p. 196, Kelly C. in speaking of the rule expressed in the maxim audi alteram partes said, “This rule is not confined to the conduct of

strictly legal tribunals, but is applicable to every tribunal or body of persons invested with authority to adjudicate upon matters involving civil consequences to individ uals.” The applicant herein by his suspension will be deprived of, at least, part of his emoluments, which deprivation is in the nature of a penalty and for such punishment to be meted against him without a hearing of his side of the story militates against even good conscience. Such a suspension is against justice and right.

[p] of [1967] GLR 536

The consequence, in my view, is that there was an abnegation of the judicial duties involved in the function of the commission of inquiry or its chairman with the result that their decision must be regarded as of no effect and invalid. It is admitted, however, that English courts cast some doubt on the scope of natural justice and in the case of Nakkuda Ali v. Jayaratne [1951] A. 66 the revocation by a government official of a textile-dealer’s licence was held by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council not to be subject to the duty to give a prior hearing to the dealer. This narrowing of the scope of natural justice was arrested by the House of Lords in R idge v. Baldwin [1964] A. 40 where the Court of Appeal had held in (as stated in the headnote to Ridge v. Baldwin [1962] 1 All E. 834 at p) that the watch committee of a local authority were under no duty in natural justice to grant the chief constable a hearing before the committee exercised its power to dismiss any constable whom they think negligent in the exercise of his duty or otherwise unfit for the same; in dismissing the plaintiff the defendants were acting in an administrative or executive capacity just as they did when they appointed him. The House of Lords overruled this view; quite apart from the procedure laid down by the disciplinary regulations, natural justice required that a hearing should have been given before the watch committee exercised its power.

There is one important emphasis made in Ridge v. Baldwin, that mere description of a statutory function as administrative, judicial, quasi-judicial or even quasi-administrative, is not in itself enough to satisfy the requirement of natural justice. As Lord Hodson said at p:

“the answer in a given case is not provided by the statement that the giver of the decision is acting in an executive or administrative capacity as if that was the antithesis of a judicial capacity. The cases seem to me to show that persons acting in a capacity which is not on the face of it judicial but rather executive or administrative have been held by the courts to be subject to the principles of natural justice.”

This all- important statement of Lord Hodson answers the contention of the respondent’s counsel that the writing of exhibit B by the chairman to suspend the applicant was done purely in his administrative capacity. This argument is blown sky-high. This emphasis of Lord Hodson is a manifestation of the growth of jurisprudence in a progressive society and the rule of natural justice could now be regarded as a sheet-anchor in protecting the individual from unfair

[p] of [1967] GLR 536

(b) appoint, transfer, suspend or dismiss any of the employees of the Corporation; and

(c) do, in furtherance of the interests of the Corporation, any other act...”

In view of the words “if the National Liberation Council is satisfied,” I am prepared to hold that conditions which may exist to enable the Council to take over the control and management of the corporation rest entirely within the absolute discretion of the Council and the grounds of their satisfaction are not open to question by the courts. But before the Council will be capable of appointing, transferring, suspending or dismissing any of the employees of the corporation there must be evidence that the Council has, in fact, in exercising its power under Part XIV of L. 397, taken over the control and management of the corporation.

This calls for examination of exhibit 2 which suspended the applicant and three other officers of the corporation. A careful examination or scrutiny of exhibit 2 does not show that the National Liberation Council has assumed control and management of the State Fishing Corporation or any part of its affairs by virtue of Part XIV of L. 397. No document in the nature of an executive instrument has been shown to this court indicating that such assumption of control has taken place. I have not seen one either. The assumption of control and management of the corporation by the National Liberation Council is a condition precedent to the exercise of any of the three powers therein stated and, in the absence of any such evidence from exhibit 2, I hold that the purported suspension of the applicant (and for that matter the other three officers) is ultra vires the National Liberation Council which acted in excess of its power.

I wish to make it abundantly clear that the National Liberation Council may occupy a dual capacity in that it has powers to enact Decrees which have the force of an Act of Parliament and it also occupies an executive position such as the deposed President occupied. It is in this latter capacity that the National Liberation Council is being considered in view of Part XIV of the State Fishing Corporation Instrument, 1965 (L. 397).

I have taken pains to bring out clearly the dual capacity of the National Liberation Council because if the Council exercises its legislative functions by promulgating Decrees, I am of the view that

[p] of [1967] GLR 536

the ultra vires doctrine cannot be used to question the validity of a Decree which, as I have stated, has the force and effect of an Act of Parliament. The position may, however, be different if the Act of Parliament or of a Legislative Assembly is in violation of the Constitution of the country. That is not the matter being considered here and, in any case, this country has no Constitution yet. But the ultra vires principle is effective to control those who exceed the administrative discretion which an Act has given. It is in this respect that the ultra vires rule may be invoked to question the validity of exhibit 2, the letter from the National Liberation Council,

suspending the applicant and the other officers mentioned therein because the prerequisites for the exercise of discretion to suspend in Part XIV of L. 397 have not been complied with.

Perhaps I may be permitted to make the bold and ex cathedra pronouncement that the discretion to suspend which may be invested in the National Liberation Council may still be questioned by these courts via a writ of certiorari as it seems the rules of natural justice have not been complied with—no hearing having been given to the applicant. I am emboldened to make this statement by what Lord Hodson said in Ridge v. Baldwin [1964] A. 40 at p. 130, H. which I have already referred to in this ruling. The language of Lord Lyndhurst C. in Capel v. Child (1832)2 C. & J. 558 offers very fruitful material for study. In that case the Bishop of London had power to appoint a court to perform, or assist in performing ecclesiastical duties and might throw the burden of the stipend of that court upon the person the insufficiency of whose performance of the duties had led to the necessity of the appointment. The Bishop appointed a curate and assigned to him a stipend but the plaintiff did not pay and he was summoned before the Bishop, but he did not attend and he was admonished to pay the stipend. He then appeared for the first time and alleged that he had not had a proper opportunity of being heard upon the original application. Here are the picturesque words of Lord Lyndhurst C. at p. 577:

“Here is a new jurisdiction given—a new authority given: a power is given to the bishop to pronounce a judgment; and, according to every principle of law and equity, such judgment could not be pronounced, or, if pronounced, could not for a moment be sustained, unless the party in the first instance had the opportunity of being heard in his defence, which in this case he had not; and not only no charge is made against him which he had an opportunity of meeting, but he has not been summoned that he might meet any charge.”

[p] of [1967] GLR 536

It is well established that the essential requirements of natural justice at least include that before someone is condemned he is to have an opportunity of defending himself, and in order that he may do so, he is to be made aware of the charges or allegations or suggestions which he has to meet: see Kanda v. Government of the Federation of Malaya [1962] A. 322, P.

Here is something which is basic to any civilised system of jurisprudence: the importance of upholding it far transcends the significance of any particular case. It would seem therefore that the National Liberation Council’s action to suspend the applicant cannot stand. However, I have not been asked to make any order against the National Liberation Council in its executive capacity and I am legally bound to refrain from offering a relief when none has been asked for. I have, however, dealt with this matter of the National Liberation Council solely on the ground that counsel for the respondent invited me to hold that exhibit 2 was an administrative action and also an answer to the applicant’s request for writs of certiorari and prohibition. I have, however, in this ruling attempted to explain why I cannot accede to counsel’s request, and the application for writs of certiorari and prohibition has been allowed as already indicated in this ruling.

Ex Parte Bannerman - case

Course: Constitutional law of Ghana and its history (FLAW306)

University: University of Ghana

- Discover more from:

Recommended for you

Students also viewed

- Judgment PS Investment V Ceredec & ORS-1

- Standard BANK Offshore Trust COMP. LT. VRS National Investment BANK & 2 ORS

- An Analysis of the Kelson S Theory of La

- Peter Ankumah V. CITY Investment CO. LTD

- Yakubu Awbego Vrs. Tindana Agongo Akubayela ; Immovable property – Allodial title to land, ownership of land, traditional evidence, resolution of conflicts arising from traditional evidence

- Attorney-General v Guardian Newspapers Ltd (No 2)