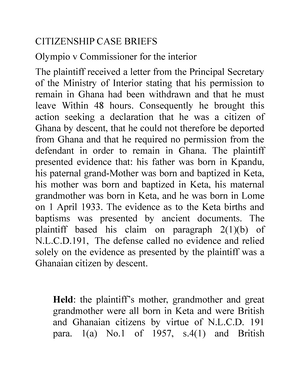

- Information

- AI Chat

Joyce v. D - It’s a case under constitutional law

Constitutional law of Ghana and its history (FLAW306)

University of Ghana

Recommended for you

Related Studylists

LawPreview text

HOUSE OF LORDS

JOYCE, APPELLANT

AND

DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS, RESPONDENT.

See [1946] A. 347 for official report

DATES: 1945 Dec. 10, 11, 12, 13, 18.

JUDGES: LORD JOWITT L., LORD MACMILLAN, LORD WRIGHT,

1946 Feb. 1.

COUNSEL: Slade K., Curtis-Bennett K. and J. Burge for the appellant.

LORD PORTER and LORD SIMONDS.

In 1933 the appellant, an American citizen, who had resided in British territory for about twenty-four years, applied for and obtained a British passport, describing himself as a British subject by birth and stating that he required it for the purpose of holiday touring in Belgium, France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy and Austria. On its expiration, he obtained renewals on September 24, 1938 and on August 24, 1939, each for a period of one year, again describing himself as a British subject. After the outbreak of war between Great Britain and Germany and before the expiration of the validity of the renewed passport, he was proved to have been employed by the German radio company and to have delivered from enemy territory broadcast talks in English hostile to Great Britain. The passport was not found in his possession when he was arrested. Having been convicted of high treason he appealed:—

Held (1.) that an alien abroad holding a British passport enjoys the protection of the Crown and if he is adherent to the King’s enemies he is guilty of treason, so long as he has not renounced that protection; (2.) (per Lord Jowitt L., Lord Macmillan Lord Wright and Lord Simonds, Lord Porter dissenting) that the judge at the trial had given a proper direction to the jury who could not have failed to appreciate from it that it was for them to consider whether at the material times the appellant continued to enjoy the protection afforded by the passport.

Per Lord Porter: The renewal of the passport did not prove conclusively in law that the duty of allegiance continued until the passport ceased to be valid, unless some action on the part of the Crown or of the appellant put an end to that protection; the onus was not on the appellant to show that the duty had been terminated.

Resolution of the judges of January 12, 1707, Foster’s Crown Cases, 3rd ed., p. 185, discussed.

Decision of the Court of Criminal Appeal (sub nom. R. v. Joyce) [1945] W. N. 220; 173 L. T. 377, affirmed. [*348]

APPEAL from the Court of Criminal Appeal.

The facts, stated by Lord Jowitt L. and Lord Porter, were as follows: The appellant, William Joyce, was charged at the Central Criminal Court on three counts, upon the third of which only he was convicted. That count was as follows:

“Statement of offence.

“High Treason by adhering to the King’s enemies elsewhere than in the King’s Realm, to wit, in the German Realm, contrary to the Treason Act, 1351.

“Particulars of offence.

“William Joyce, on September 18, 1939, and on divers other days thereafter and between that day and July 2, 1940, being then — to wit on the several days — a person owing allegiance to our Lord the King, and whilst on the said several days an open and public war was being prosecuted and carried on by the German Realm and its subjects against our Lord the King and his subjects, then and on the said several days traitorously contriving and intending to aid and assist the said enemies of our Lord the King against our Lord the King and his subjects did traitorously adhere to and aid and comfort the said enemies in parts beyond the seas without the Realm of England, to wit, in the Realm of Germany by broadcasting to the subjects of our Lord the King propaganda on behalf of the said enemies of our Lord the King.”

The first and second counts, upon which the appellant was found not guilty, were based upon the assumption that he was at all material times a British subject. This assumption was proved to be incorrect; therefore upon these counts the appellant was acquitted.

The appellant was born in the United States of America, in 1906, the son of a naturalized American citizen who had previously been a British subject by birth. He thereby became himself a natural born American citizen. At about three years of age he was brought to Ireland, where he stayed until about 1921, when he came to England. He stayed in England until 1939. He was then thirty-three years of age. He was brought up and educated within the King’s Dominions, and he settled there. On July 4, 1933, he applied for a British passport, describing himself as a British subject by birth, born in Galway. He asked for the passport for the purpose of holiday touring in Belgium, France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy and Austria. He was granted the passport for a period of five [*349] years. The document was not produced,

ever availed himself or had any intention of availing himself of any such protection. (4.) If (contary to the appellant’s contention) there were any such evidence, the issue was one for the jury and the learned judge failed to direct them thereon.” On November 7, 1945, the Court of Criminal Appeal dismissed the appeal. The Attorney- General certified under s. 1, sub-s. 6, of the Criminal Appeal Act, 1907, that the decision of the Court of Criminal Appeal involved a point of law of exceptional public importance and that in his opinion it was desirable in the public interest that a further appeal should be brought. The appellant accordingly appealed to the House of Lords.

Slade K., Curtis-Bennett K. and J. Burge for the appellant. It is clear that if this conviction be upheld an alien holding a British passport owes allegiance during its unexpired validity wherever he goes and no matter what he does. The case for the appellant rests on five submissions: (a) The local allegiance due from an alien continues so long only as he is personally present within the King’s dominions. (b) The protection which is the counterpart of the local allegiance due from an alien is the protection of our laws and is co-extensive with our legal jurisdiction. It is that which was referred to [*351] in Calvin’s case(1) in the maxim: Protectio trahit subjectionem, et subjectio protectionem. (c) Protection means the right to protection and not merely the de facto enjoyment of it, which might be had by a person who obtained a passport by fraud. (d) No court in this country has jurisdiction to try an alien for an offence alleged to have been committed abroad except only in the two cases of piracy jure gentium and an offence committed on board a British ship. Though the legislature would have power to make treason also an exception it has not done so. The Treason Act, 1351, speaks of “a man” — “home” is the actual word used — and the comity of nations requires that that word should be interpreted as a man owing allegiance to the Crown, that is to say a British subject wherever he may be or an alien so long only as he is physically present within the King’s dominions. (e) There is no evidence that the renewal of the appellant’s passport afforded him or was capable of affording him any protection or that he ever availed himself or intended to avail himself of such protection. Further, even if there was any such evidence, the issue was one for the jury and the learned judge failed to direct them on it. The submission which depends on local allegiance is complementary to that depending on jurisdiction, for whenever an alien leaves the realm local allegiance ceases and he can no longer be tried by the courts of this country. As regards the first point, that an alien owes a local allegiance only so long as he resides within the King’s dominions, the nature of allegiance has been long settled: see Calvin’s case(2) and In re Stepney Election Petition (3). A man cannot be guilty of treason if he does not owe allegiance. An act which is treasonable if he owes allegiance is not treasonable if he does not. The allegiance due from an alien is accurately laid down in Blackstone’s Commentaries, 1st ed., vol. 1, pp. 357-9: “Allegiance, both express and implied, is however distinguished by the law into two sorts or species, the one natural, the other local; the former being also perpetual, the latter temporary. .... Local allegiance is such as is due from an alien, or stranger born, for so long time as he continues within the King’s dominion and protection: and it ceases the instant such stranger transfers himself from this Kingdom

to another. ... As therefore the prince is always under a constant tie to protect his

(1) (1608) 7 Co. Rep. 1a, 5a.

(2) Ibid. 1a, 4b, 5b.

(3) (1886) 17 Q. B. D. 54, 64.

[*352] natural-born subjects, at all times and in all countries, for this reason their allegiance due to him is equally universal and permanent. But, on the other hand, as the prince affords his protection to an alien, only during his residence in this realm, the allegiance of an alien is confined (in point of time) to the duration of such his residence, and (in point of locality) to the dominions of the British empire. ...” Here residence means personal presence within the realm. It has been suggested that this principle is qualified by a passage in Foster’s Crown Cases, 1792 ed., p. 185: “And if such alien seeking the protection of the Crown; and having a family and effects here, should during a war with his native country, go thither, and adhere to the King’s enemies for purposes of hostility, he might be dealt with as a traitor. For he came and settled here under the protection of the Crown; and though his person was removed for a time, his effects and family continued still under the same protection. This rule was laid down by all the judges assembled at the Queen’s command, January 12, 1707.” In the margin “Mss. Tracy, Price, Dod and Denton” are cited but the original manuscript cannot be found. This resolution, which is the only authority for the Crown, is also set out, quoting Foster, in Bacon’s Abridgement, 7th ed., vol. VII., pp. 583-4, East’s Pleas of the Crown, 1803 ed., vol. I., p. 53, Chitty’s Prerogatives of the Crown, p. 13, and Hawkins’; Pleas of the Crown, 8th ed., vol. I., p. 8 n., most of these treating it with reserve. It is bad law, quite inconsistent with Johnstone v. Pedlar (1), and merely the opinion of the judges in consultation with prosecuting counsel. It was not given as a decision in any case and so is not binding as an authority. An account of this practice may be found in an article on The History of the Parliamentary Declaration of Treason, by Professor Samuel Rezneck (1930) 46 Law Quarterly Review, p. 80, at pp. 85-7. It may be inferred that this resolution had reference to the statute 9 W. 3, c. 1, which made it treason for any person who had been in England before December 11, 1688, and had gone abroad, to return again without leave. R. v. Lindsay (2) and R. v. Gregg (3) were prosecutions under this Act. It would appear probable that the resolution was designed to show that there was no legal bar to trying Bara and Valiere mentioned in R. v. Gregg (4). See also Smollett’s History of England, vol. II., p. 180. In any

(1) [1921] 2 A. C. 262, 292, 297.

(2) (1704) 14 St. Tr. 987.

(3) (1708) 14 St. Tr. 1371.

(4) Ibid. 1375.

his country, and had joined the German army within that period, he would have been liable to be convicted of treason. Again, if a British subject lawfully holding a British passport went to America and became naturalized there, then although by statute he ceased to be a British subject immediately on his naturalization, yet he would continue to owe allegiance to the British Crown for the unexpired term of his passport. [They referred to De Jager v. Attorney-General for Natal (1); R. v. Brailsford (2); Carlisle v. United States (3); United States v. Villato (4); two articles on Citizenship and Allegiance by Sir John Salmond (1901) 17 Law Quarterly Review, p. 270; (1902) 18 Law Quarterly Review, pp. 49, 61, 62; an article on The Passport System by W. N. Sibley (1906) 7 Journal of Comparative Legislation (N. S.), p. 26, and Parl. Papers (1872), vol. 70, c. 529 and (1887), vol. 81, c. 5168.]

On the — fourth point that no British court has jurisdiction to try an alien for an offence alleged to have been committed abroad, even on the assumption that the appellant owed allegiance to the British Crown after leaving England, he could still not be tried here (1.) because no statute gives jurisdiction to try an alien for such an offence and (2.) because otherwise it would always be possible merely by alleging that any person owed allegiance to bring him within the jurisdiction of the courts of this country for trial of the question whether he owed allegiance or not. There is a distinction between substantive crime and the jurisdiction to try it. For the court to be able, merely by alleging allegiance to give itself jurisdiction to try the question of law whether or not there was allegiance would offend against the principle that no court can confer jurisdiction on itself. The court admittedly derives jurisdiction to try a British subject by alleging that he is a British subject, but there is a difference

(1) [1907] A. C. 326.

(2) [1906] 2 K. B. 730 [sic, should be [1905] 2 K. 730].

(3) (1872) 16 Wallace 147, 153.

(4) (1797) 2 Dallas 370.

[*355] between alleging that a person is a British subject, a fact which founds the courts jurisdiction if it is true, and alleging allegiance which is only a factor in the particular offence charged. Apart from the Naturalization Act, 1870, the general principle still holds good. Nemo potest exuere patriam. Nothing a man does can make him a British subject and nothing he can omit to do can prevent him from being a British subject if he was so born. In the case of a foreigner committing an offence outside British territory, British courts have no jurisdiction to try him: see Halsbury’s Laws of England, 2nd ed., vol. IX., pp. 55-6, 62. In construing an Act of Parliament there is a presumption against a violation of international law: Maxwell on Interpretation of Statutes, 8th ed., p. 130. That applies to the Treason Act, 1351. Two later statutes dealt with the trial of treasons committed abroad, both of them purely procedural, the Treason Act, 1543 (35 Hen. 8, c. 2) and the Treason Act, 1551 (5 & 6 Edw. 6, c. 11), the latter repealed by the Treason Act, 1945 (8 & 9 Geo. 6, c. 44). The Treachery Act, 1940 (3 &

4 Geo. 6, c. 21), s. 4, shows how the legislature has regard to the comity of nations by its careful definition of the persons who can be guilty of offences created by the Act. The only possible application of that Act to an alien is in respect of an offence committed by him while subject to naval, military or air force law. [They referred to Reg. v. Jameson (1); Macleod v. Attorney-General for New South Wales (2) and Attorney-General for Hong Kong v. Kwok-a-Sing (3).]

On the final points that there was no evidence that the passport ever afforded the appellant any protection and that, if there was such evidence, the issue was one for the jury, even if the resolution of the judges in 1707 were correct, the effect of the ruling of Tucker J., would be to extend it, since none of the prerequisites set out in it were present in the case of the appellant. He left no family or effects in England and the protection which would have been afforded to them if he had bore no relation to the administrative protection alleged to be afforded by a passport. After the outbreak of war the British passport could afford the appellant no protection in Germany and there was no direct evidence that at any material time it remained in his possession. Even assuming that all the previous submissions for the appellant are wrong and that the mere granting of a passport

(1) [1896] 2 Q. B. 425, 430, 431.

(2) [1891] A. C. 455, 459.

(3) (1873) L. R. 5 P. C. 179, 198, 199.

[*356] to an alien imports a duty of allegiance by him to the Crown, even so he must be able to divest himself of the protection which gave rise to the allegiance. It cannot be the law that whatever happens and in all circumstances the alien must continue under that allegiance for the period during which the passport happens to remain in force. Accordingly, it must be a question of fact in each case — it cannot be one of law — by what act and at what date he divested himself of the protection and the corresponding allegiance. The onus was on the Crown to prove that he had not done anything to divest himself of the protection of the passport. Even if the mere fact that he obtained a passport raised a prima facie case and shifted the burden of proof on to him, the question of fact involved must be left to the jury. It was the judge’s duty in this case to direct them what the evidence was and to tell them that evidence which was sufficient to call for an answer from the defence was not necessarily enough to satisfy them. In any event the issue must be left to them and here it had not been. Tucker J. directed them as a matter of law that the appellant continued to owe allegiance throughout the currency of his passport. [They referred to Stirland v. Director of Public Prosecutions (1).] As regards R. v. Casement (2) that case is irrelevant to any of the issues raised by this appeal, because Casement was not an alien but a British subject. Moreover. it was, in any event, wrongly decided.

Sir Hartley Shawcross A.-G. and Gerald Howard for the Crown. The appellant contended that the judges’ resolution of January 12, 1707, was the only authority for the Crown. That resolution was made

regard to his acquisition of German nationality is not a thing on which he can rely, for it was not

(1) [1917] 1 K. B. 98.

(2) [1896] 2 Q. B. 425, 430.

(3) 7 Co. Rep. 1a, 5a.

[*358] an admission but an assertion in his own favour. Since he did not choose to go into the witness-box it is not evidence. The passport granted to him in 1933 was for the purpose of holiday touring. The renewals were unqualified and an application for plain renewal of a passport must be presumed to be for the same purpose as the original. A person going abroad for a holiday for a week or a month does not cease to be resident in this country. Moreover, the appellant did not need a British passport merely to leave England nor, if he could establish his American nationality, to enter the United States. One of the uses of a passport is that the country issuing it to any person is, under international conventions, bound to receive him back. Further, the passport was evidence that he was under the protection of the Crown. It was accepted as proof that he was a British subject and as such he acquired his position in Germany. It was the fact that he held himself out as such that made his broadcasts effective. As to the nature of the protection which a passport affords to an alien, it is not the protection of our laws. Originally, when protection depended on the strong arm of the feudal lord, aliens were granted by the Crown an executive protection against our laws, the passport enabling them to pass freely in this country, protected from the ordinary operation of laws which were highly restrictive and penal as regards foreigners. It was a document permitting them to travel within the state’s own boundaries: see the article on The Crown and the Alien by E. F. Churchill (1920), 36 Law Quarterly Review, p. 402. There is not really any connexion between such a document and a modern passport, which is a matter of international practice. In modern practice the State takes under its protection persons who are not British subjects, who have then the status of protected persons and such was the appellant. Inasmuch as this species of protection is not the protection of our laws, even a British subject has no legally enforceable right to the protection of the Crown abroad. It is a prerogative right in the Crown to protect its own subjects abroad by diplomatic means and this was illustrated in 1850 in the incident of Don Pacifico. The exercise of the protective jurisdiction here contended for is well recognized in international law: see Oppenheim on International Law, 5th ed., p. 267; art. 7 of the Draft Convention on Jurisdiction in Respect of Crime (Harvard Research (1935), p. 545) and Borchard on the Diplomatic Protection of Citizens Abroad, pp. 10, 29. The passport is now the method by which the Crown accords [*359] his protection to persons abroad. It is the sovereign’s express command to his representatives that protection is to be given and in its normal functioning puts into operation the Crown’s protective system. The resident alien shares now in the general protection of all the inhabitants of the realm but the passport holder has the benefit of a protective machinery going much further, even to the point of involving the country in war: see article on

International Law in Practice by Sir William Malkin (1933), 49 Law Quarterly Review, p. 489, and Encyclop3Ú4dia of the Laws of England, 2nd ed., vol X., p. 585, et seq. This was the nature of the protection which in this case imposed on the appellant the duty of allegiance. Some dicta in the authorities, when divorced from their context, may appear to support the view that the protection to be afforded to produce that result is that of our laws, but the danger of treating dicta in that way is illustrated by Sovfracht (V/O) v. Van Udens Scheepvaart en Agentuur Maatschappij (N. V. Gebr.) (1). To impose the duty of allegiance it is enough if the State has accorded protection to a person seeking it and is able to give it to the extent recognized by international law. If the appellant’s argument were right a subject of a British mandated, or even a British protected, territory, holding, as such a person does, a British passport, would be under no duty of allegiance to the Crown. That could have far-reaching and serious consequences. The appellant enjoyed exactly the same protection, whether it were called protection of law, or protection in fact, as any British subject would have enjoyed in the same circumstances at the same time. Though the right to protection might be in suspense, the duty of allegiance remained. Even in Germany after the outbreak of war the administrative protection was not withdrawn, though direct protection by the Crown’s representatives might have come to an end. The Crown continued to exercise protection through the medium of the protecting power and the holder of a British passport might benefit from that. Thus, a British subject could not be called up to serve in the German army. In international law it is not open to a foreign state to disregard a British passport and deny its holder’s nationality. It is immaterial that it may have been obtained by a false, or even a fraudulent, representation. The protection conferred continues until the Crown withdraws it. Similarly, just as a British subject can terminate his allegiance by becoming a naturalized

(1) [1943] A. C. 203.

[*360] citizen of a foreign state, so the protected person can by some overt act of substance terminate his allegiance, which does not necessarily continue during the whole of the passport’s validity. The passport is evidence of the existence of protection and if the appellant had discarded it on a return to England that might make a difference, though his merely handing it back to a British consul in Germany might not justify this country in subsequently refusing to admit him. From the application for the passport and its renewals it must be presumed that the appellant used it for going abroad. That inference is a matter of accepted international law. Having sought the protection of the Crown, the appellant has also the burden of showing that it was not in fact afforded. The applications were the best prima facie evidence that he intended to avail himself of it. It was for him to show that he had by some overt act divested himself of the status he had acquired. Negative averments only in the knowledge of the accused and not of the Crown must be proved by him: Archbold’s Criminal Practice (31st ed.) (1943), p. 330. The summing-up satisfied the tests laid down in Stirland v. Director of Public Prosecutions (1) approving R. v. Haddy (2). Once a man has obtained the general administrative and executive protection of the Crown, there is no principle limiting his allegiance by

of the law there was no point in insisting on the necessity for the presence in this country of the alien’s family or effects. The effect of this conviction is to contradict that and say that the protection attracting allegiance is not that of our law in the case of a person holding a British passport. But allegiance is derived from status, the status of a subject. A resident alien is a subject and when he ceases to reside he

(1) 7 Co. Rep. 1a.

(2) [1921] 2 A. C. 262.

(3) 14 St. Tr. 787.

(4) 14 St. Tr. 1371, 1375.

[*362] ceases to be a subject: see Sir John Salmond on Citizenship and Allegiance (1902) 18 Law Quarterly Review, pp. 49, 50. This is quite inconsistent with the judges’ resolution of 1707. An alien soldier in the British service could not be tried for treason for an act committed abroad, for his oath of allegiance would not constitute the status of local allegiance. There is no reported case of an alien mercenary being tried for such an act. Before 1940 he would have been tried under s. 4 of the Army Act and since then he would be triable under the Treachery Act, 1940. There is no intermediate status between a British subject and an alien called a “British protected subject.” The de facto protection afforded by a British mandate does not beget allegiance. British subjects alone are entitled when abroad to the protection of the Crown against other states: see Sir John Salmond on Citizenship and Allegiance (1901) 17 Law Quarterly Review, pp. 270, 271; Abd-ul-Messih, v. Farim (1); Markwald v. Attorney-General (2) and R. v. Ketter (3). Even in the case of British subjects it lies within the Crown’s discretion whether or not to take diplomatic action on behalf of one of its nationals: see the article by Sir William Malkin on International Law in Practice (1933) 49 Law Quarterly Review, pp. 489, 498-9, which does not deal with passports at all. It is a fallacy to suggest that any protection is afforded by a passport qua passport; it is only an easy means of identification. An alien who has obtained a British passport, with whatever protection he might get from the belief that he is a British subject, can have no higher degree of protection than a British protected person, and that cannot found allegiance. The Crown admitted that this conviction would have been good in law if the appellant had been a German when he left the country. That would give rise to extraordinary situations, so that if a German spy wished, in obedience to his natural instincts to return to Germany when war with England became imminent and obtained a British passport, since that was the only way he could go out of the country, he would be held guilty of treason. As regards jurisdiction, there is no case in which a court in England has assumed jurisdiction to try an alien for an offence committed abroad: see Mortensen v. Peters (4); Johnstone v. Pedlar (5); The Fagernes (6).

(1) (1888) 3 App. Cas. 431, 443 [sic, should be: Abd-ul- Messih v. Farra, 13 App. Cas. 431].

(2) [1920] 1 Ch. 348, 355.

(3) [1940] 1 K. B. 787, 788.

(4) (1906) 8 F. (J. C.) 93.

(5) [1921] 2 A. C. 262.

(6) [1927] P. 311.

[*363] As regards the case of De Jager v. Attorney-General for Natal (1) that was a bad decision: see the discussion of it in Current Noteson International Law (1908) 33 Law Magazine and Review, 4th series, pp. 214-18. In general, it is a singularly sterile process to try to interpret the Treason Act, 1351, by reference to modern concepts of international law, which did not then exist in more than an embryonic state. Confusion has arisen between the intention with which the appellant left England, whether he had any animus revertendi, and the use which he may have made of the passport after he got to Germany. The fact of his joining the German radio organization indicated an intention not to return and a casting off of any protection provided by the passport. He had deserted what he took to be a sinking ship and any intention he may have had of returning was not a return to the Crown’s allegiance but with a victorious German army. As regards the passport so far as the evidence goes he might have thrown it overboard during the sea crossing from England. There is no complaint of the judge’s summing-up on the facts proved in evidence but he failed to direct the jury on facts about which no evidence had been given but which were for them and on an issue which should have been left to them. Even if it was for the appellant to show what was done with the passport the judge should have directed the jury on that matter. Further, he directed them as a matter of law that the appellant continued to owe allegiance to the Crown at the material times and that was an issue which should have been left to them. It could not be said that a reasonable jury if they had received the directions which were lacking would necessarily have reached the same conclusion. Since the issue was not put to the jury at all the proviso to s, 4, sub-s. 1 of the Criminal Appeal Act, 1907, does not operate.

December 18, 1945. LORD JOWITT L. I have come to the conclusion, in common with the majority of your Lordships, that the appeal should be dismissed. I should propose to deliver my reasons at a later date.

LORD MACMILLAN. I agree.

LORD WRIGHT. I also agree.

LORD PORTER. In agreement with all your Lordships, I think that the renewal of his passport, which Joyce obtained

(1) [1907] A. C. 326.

realm giving them aid and comfort in the realm, or elsewhere” then (I depart from the text and use modern terms) he shall be guilty of treason. It is not denied that the appellant has adhered to the King’s enemies giving them aid and comfort elsewhere than in the realm. Upon this part of the case the single question is whether, having done so, he can be and in the circumstances of the case is guilty of treason. Your Lordships will observe that the statute is wide enough in its terms to cover any man anywhere, “if a man do levy war,” etc. Yet it is clear that some limitation must be placed upon the generality of the language, for the context in the preamble poses the question “in what case treason shall be said and in what not.” It is necessary then to prove not only that an act was done but that, being done, it was a treasonable act. This must depend upon one thing only, namely the relation in which the actor stands to the King to whose enemies he adheres. An act that is in one man treasonable, may not be so in another. In the long discussion which your Lordships have heard upon this part of the case attention has necessarily been concentrated on the question of allegiance. The question whether a man can be guilty of treason to the King has been treated as identical with the question whether he owes allegiance to the King. An act, it is said, which is treasonable if the actor owes allegiance, is not treasonable if he does not. As a generalization, this is undoubtedly true and is supported by the language of the indictment, but it leaves undecided the question by whom allegiance is owed and I shall ask your Lordships to look [*366] somewhat more deeply into the principle upon which this statement is founded, for it is by the application of principle to changing circumstances that our law has developed. It is not for His Majesty’s judges to create new offences or to extend any penal law and particularly the law of high treason, but new conditions may demand a reconsideration of the scope of the principle. It is not an extension of a penal law to apply its principle to circumstances unforeseen at the time of its enactment, so long as the case is fairly brought within its language.

I have said, my Lords, that the question for consideration is bound up with the question of allegiance. Allegiance is owed to their sovereign Lord the King by his natural born subjects; so it is by those who, being aliens, become his subjects by denization or naturalization (I will call them all “naturalized subjects”); so it is by those who, being aliens, reside within the King’s realm. Whether you look to the feudal law for the origin of this conception or find it in the elementary necessities of any political society, it is clear that fundamentally it recognizes the need of the man for protection and of the sovereign lord for service. “;Protectio trahit subjectionem et subjectio protectionem.” All Who were brought within the King’s protection were ad fidem regis: all owed him allegiance. The topic is discussed with much learning in Calvin’s case (1). The natural-born subject owes allegiance from his birth, the naturalized subject from his naturalization, the alien from the day when he comes within the realm. By what means and when can they cast off allegiance? The natural-born subject cannot at common law at any time cast it off. “Nemo potest exuere patriam” is a fundamental maxim of the law from which relief was given only by recent statutes. Nor can the naturalized subjects at common law. It is in regard to the alien resident within the realm that the controversy in

this case arises. Admittedly he owes allegiance while he is so resident, but it is argued that his allegiance extends no further. Numerous authorities were cited by the learned counsel for the appellant in which it is stated without any qualification or extension that an alien owes allegiance so long as he is within the realm and it has been argued with great force that the physical presence of the alien actor within the realm is necessary to make his act treasonable. It is implicit in this argument that during absence from the realm, however

(1) 7 Co. Rep. 1a.

[*367] brief, an alien ordinarily resident within the realm cannot commit treason; he cannot in any circumstances by giving aid and comfort to the King’s enemies outside the realm be guilty of a treasonable act. My Lords in my opinion this which is the necessary and logical statement of the appellant’s case is not only at variance with the principle of the law, but is inconsistent with authority which your Lordships cannot disregard. I refer first to authority. It is said in Foster’s Crown Cases (3rd ed.), p. 183 — “Local allegiance is founded in the protection a foreigner enjoyeth for his person, his family or effects, during his residence here; and it ceaseth, whenever he withdraweth with his family and effects.” And then on p. 185 comes the statement of law upon which the passage I have cited is clearly founded “Section 4. And if such alien, seeking the protection of the Crown, and having a family and effects here, should during a war with his native country, go thither, and there adhere to the King’s enemies for purposes of hostility, he might be dealt with as a traitor. For he came and settled here under the protection of the Crown; and, though his person was removed for a time, his effects and family continued still under the same protection. This rule was laid down by all the judges assembled at the Queen’s command January 12, 1707.” The author has a side note against the last line of this passage “MSS. Tracey, Price, Dod and Denton.” These manuscripts have not been traced but their authenticity is not questioned. It is indeed impossible to suppose that Sir Michael Foster could have incorporated such a statement except upon the surest grounds and it is to be noted that he accepts equally the fact of the judges’ resolution and the validity of its content. This statement has been repeated without challenge by numerous authors of the highest authority — e., Hawkins, Pleas of the Crown, 1795 ed., c. II., s. 5, n, (2.); East, Pleas of the Crown, vol. I., p. 52; Chitty on the Prerogatives of the Crown, pp. 12, 13. It may be said that the language of some of these writers is not that of enthusiastic support, but neither in the text books written by the great masters of this branch of the law nor in any judicial utterance has the statement been challenged. Moreover it has been repeated without any criticism in our own times by Sir William Holdsworth whose authority on such a matter is unequalled: see his article in Halsbury’s Laws of England (2nd ed.), vol. VI., p. 416 n. (t.), title “Constitutional Law.” Your Lordships can give no weight to the fact that in [*368] such cases as Johnstone v. Pedlar (1), the local allegiance of an alien is stated without qualification to be coterminous with his residence within the realm. The qualification that we are now discussing was not relevant to the issue nor brought to the mind of the court. Nor was the judges’ resolution referred to nor the meaning of “residence”

asserting that he was a British subject by birth, a statement that he was afterwards at pains to disprove. It may be that when he first made the statement, he thought it was true. Of this there is no evidence. The essential fact is that he got the passport and I now examine its effect. The actual passport issued to the appellant has not been produced, but its contents have been duly proved. The terms of a passport are familiar. It is thus described by Lord Alverstone C., in R. v. Brailsford (1): “It is a document issued in the name of the sovereign on the responsibility of a minister of the Crown to a named individual, intended to be presented to the governments of foreign nations and to be used for that individual’s protection as a British subject in foreign countries.” By its terms it requests and requires in the name of His Majesty all those whom it may concern to allow the bearer to pass freely without let or hindrance and to afford him every assistance and protection of which he may stand in need. It is, I think, true that the possession of a passport by a British subject does not increase the sovereign’s duty of protection, though it will make his path easier. For him it serves as a voucher and means of identification. But the possession of a passport by one who is not a British subject gives him rights and imposes upon the sovereign obligations which would otherwise not be given or imposed. It is

(1) [1905] 2 K. B. 730, 745.

[*370] immaterial that he has obtained it by misrepresentation and that he is not in law a British subject. By the possession of that document he is enabled to obtain in a foreign country the protection extended to British subjects. By his own act he has maintained the bond which while he was within the realm bound him to his sovereign. The question is not whether he obtained British citizenship by obtaining the passport, but whether by its receipt he extended his duty of allegiance beyond the moment when he left the shores of this country. As one owing allegiance to the King he sought and obtained the protection of the King for himself while abroad.

Your Lordships were pressed by counsel for the appellant with a distinction between the protection of the law and the protection of the sovereign, and he cited many passages from the books in which the protection of the law was referred to as the counterpart of the duty of allegiance. Upon this he based the argument that, since the protection of the law could not be given outside the realm to an alien, he could not outside the realm owe any duty. This argument in my opinion has no substance. In the first place reference is made as often to the protection of the Crown or sovereign or lord or government as to the protection of the law, sometimes also to protection of the Crown and the law. In the second place it is historically false to suppose that in olden days the alien within the realm looked to the law for protection except in so far as it was part of the law that the King could by the exercise of his prerogative protect him. It was to the King that the alien looked and to his dispensing power under the prerogative. It is not necessary to trace the gradual process by which the civic rights and duties of a resident alien became assimilated to those of the natural-born subject; they have in fact been assimilated, but to this day there will be found some difference. It is sufficient to say that at

the time when the common law established between sovereign lord and resident alien the reciprocal duties of protection and allegiance it was to the personal power of the sovereign rather than to the law of England that the alien looked. It is not, therefore, an answer to the sovereign’s claim to fidelity from an alien without the realm who holds a British passport that there cannot be extended to him the protection of the law. What is this protection upon which the claim to fidelity is founded? To me, my Lords, it appears that the Crown in issuing a passport is assuming an onerous burden, and the holder of the passport is acquiring substantial [*371] privileges. A well known writer on international law has said (see Oppenheim, International Law, 5th ed., vol. I., p. 546) that by a universally recognized customary rule of the law of nations every state holds the right of protection over its citizens abroad. This rule thus recognized may be asserted by the holder of a passport which is for him the outward title of his rights. It is true that the measure in which the state will exercise its right lies in its discretion. But with the issue of the passport the first step is taken. Armed with that document the holder may demand from the State’s representatives abroad and from the officials of foreign governments that he be treated as a British subject, and even in the territory of a hostile state may claim the intervention of the protecting power. I should make it clear that it is no part of the case for the Crown that the appellant is debarred from alleging that he is not a British subject. The contention is a different one: it is that by the holding of a passport he asserts and maintains the relation in which he formerly stood, claiming the continued protection of the Crown and thereby pledging the continuance of his fidelity. In these circumstances I am clearly of opinion that so long as he holds the passport he is within the meaning of the statute a man who, if he is adherent to the King’s enemies in the realm or elsewhere commits an act of treason. There is one other aspect of this part of the case with which I must deal. It is said that there is nothing to prevent an alien from withdrawing from his allegiance when he leaves the realm. I do not dissent from this as a general proposition. It is possible that he may do so even though he has obtained a passport. But that is a hypothetical case. Here there was no suggestion that the appellant had surrendered his passport or taken any other overt step to withdraw from his allegiance, unless indeed reliance is placed on the act of treason itself as a withdrawal. That in my opinion he cannot do. For such an act is not inconsistent with his still availing himself of the passport in other countries than Germany and possibly even in Germany itself. It is not to be assumed that the British authorities could immediately advise their representatives abroad or other foreign governments that the appellant, though the holder of a British passport, was not entitled to the protection that it appeared to afford. Moreover the special value to the enemy of the appellant’s services as a broadcaster was that he could be represented as speaking as a British subject and his German work book showed that it was in this character that he was [*372] employed, for which his passport was doubtless accepted as the voucher.

The second point of appeal (the first in formal order) was that in any case no English court has jurisdiction to try an alien for a crime committed abroad and your Lordships heard an exhaustive argument

Joyce v. D - It’s a case under constitutional law

Course: Constitutional law of Ghana and its history (FLAW306)

University: University of Ghana

- Discover more from: