- Information

- AI Chat

Republic V HIGH Court (COM. DIV.), Accra,NML EX Parte Attorney- General (Autosaved)

Constitutional law of Ghana and its history (FLAW306)

University of Ghana

Recommended for you

Students also viewed

- Judgment PS Investment V Ceredec & ORS-1

- Standard BANK Offshore Trust COMP. LT. VRS National Investment BANK & 2 ORS

- An Analysis of the Kelson S Theory of La

- Peter Ankumah V. CITY Investment CO. LTD

- Yakubu Awbego Vrs. Tindana Agongo Akubayela ; Immovable property – Allodial title to land, ownership of land, traditional evidence, resolution of conflicts arising from traditional evidence

- Attorney-General v Guardian Newspapers Ltd (No 2)

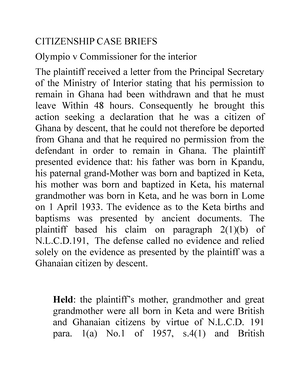

Preview text

1 IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF JUDICATURE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF GHANA ACCRA, 2013 CORAM: DR. DATE-BAH JSC (PRESIDING) DOTSE JSC YEBOAH JSC GBADEGBE JSC AKAMBA JSC CIVIL MOTION No/10/2013 20TH JUNE, 2013 IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION TO INVOKE THE SUPERVISORY JURISDICTION OF THE SUPREME COURT ARTICLES 88(6) AND 132 OF THE 1992 CONSTITUTION, RULE 61 OF THE SUPREME COURT RULES, 1996 (C.I) THE REPUBLIC VRS. HIGH COURT (COMM. DIV.) ACCRA EX PARTE; ATTORNEY GENERAL - - - APPLICANT NML CAPITAL LTD --1ST INTERESTED PARTY THE REPUBLIC OF ARGENTINA - - - 2ND INTERESTED PARTY RULING 1 2 DR. DATE- BAH JSC: Introductory Analysis of the Relationship between International Law and Ghanaian Municipal Law. This case raises important issues on the nature of the relationship between international law and municipal law in Ghana. The main purpose of the learned Attorney-General in bringing this application for certiorari and prohibition would seem to be to enable the Republic to comply with the orders of the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (hereafter referred to as the “Tribunal”), established under the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention. This circumstance raises the question, quite apart from the other legal issues which arise in this case, whether this court or any other court of Ghana is obliged to enforce the orders of the Tribunal. Before entering into the full details of the facts of this case, it would thus be worth our while to examine this question of the relationship between international law and municipal law in Ghana. Ghanaian law on this basic question is no different from the usual position of Commonwealth common law jurisdictions. It is that customary international law is part of Ghanaian law; incorporated by the weight of common law case law (for instance, Triquet v Bath (1764) 3 Burr. 1478 (Court of King’s Bench) and per Lord Denning in Trendtex Trading Corporation v Central Bank of Nigeria [1977] QB 529 (Court of Appeal)).In Chung Chi Cheung v The King[1939] AC 160,the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, speaking through Lord Atkin, stated this common law position as follows (at p. 168): “The courts acknowledge the existence of a body of rules which nations accept among themselves. On any judicial issue they seek to ascertain what the relevant rule is, and, having found it, they will treat it as incorporated into the domestic law, so far as it is not inconsistent with rules enacted by statutes or finally declared by their tribunals.” However, treaties, even when the particular treaty has been ratified by Parliament, do not alter municipal law until they are incorporated into Ghanaian law by appropriate legislation. 2 4 “(1) The President may execute or cause to be executed treaties, agreements or conventions in the name of Ghana. (2) A treaty, agreement or convention executed by or under the authority of the President shall be subject to ratification by(a) Act of Parliament; or (b) a resolution of Parliament supported by the votes of more than onehalf of all the members of Parliament.” The mere fact that a treaty has been ratified by Parliament through one of the two modes indicated above does not, of itself, mean that it is incorporated into Ghanaian law. A treaty may come into force and regulate the rights and obligations of the State on the international plane, without changing rights and obligations under municipal law the mode of ratification adopted is through an Act of Parliament, that Act may incorporate the treaty, by appropriate language, into the municipal law of Ghana. It follows from the foregoing analysis that the following proposition of law made by the applicant in para 30 of his Statement of Case is completely erroneous: “It will be recalled that incorporation of treaty-based public international law into Ghana law is through Article 75 of the 1992 Constitution which states that an international treaty or agreement becomes effective in Ghana once ratified by Parliament.” This analysis applies equally to the provision in the “constitution” in force in Ghana at the time UNCLOS was ratified. That was section 8(2) of the Provisional National Defence Council (Establishment) Proclamation 1981 (PNDCL 42), which stated: “The Council shall execute or cause to be executed treaties, agreements or conventions in the name of Ghana, so however that such treaties,agreements or conventions shall come into force on ratification by the Council.” 4 5 In any case, in relation to UNCLOS, there has been no incorporation of its provisions into Ghanaian municipal law, except to a limited extent in the Maritime Zones (Delimitation) Act, 1986 (PNDCL 159). The need for the legislative incorporation of treaty provisions into municipal law before domestic courts can apply those provisions is reflective of the dualist stance of Commonwealth common law courts and backed by a long string of authorities, such as The ParlementBelge [1880] 5PD 197 (English Court of Appeal); Walker v Baird [1892] AC 491 at 497 (English House of Lords); Attorney-General (Canada) v Attorney-General (Ontario) [1937] AC 326 (Judicial Committee of the Privy Council), per Lord Atkin at p. 347; Theophile v Solicitor-General [1950] AC 186, at pp 195-6 (English House of Lords);J. Rayner (Mincing Lane) Ltd. v Dept of Trade and Industry [1990] AC 418, at p (English House of Lords); Chow Hung Ching v R (1948) 77 CLR 449 at p. 478, per Dixon J. (High Court of Australia) and New Zealand Airline Pilots’ Association v Attorney-General [1997] 3 NZLR 269 at pp. 280-1 (New Zealand Court of Appeal). In delivering the judgment of the New Zealand Court of Appeal in the last case, Keith J., in answer to the question: “Is the Chicago Convention part of the law of New Zealand?”, stated pithily (at pp 280-1) that: “As Lord Atkin said for the Privy Council in Attorney-General for Canada v AttorneyGeneral for Ontario [1937] AC 326 at p. 347, it is well established that while the making of a treaty is an Executive act, the performance of its obligations, if they entail alteration of the existing domestic law, requires legislative action. The stipulations of a treaty duly ratified by the Executive do not, by virtue of the treaty alone, have the force of law.” The New Zealand Court of Appeal reached another decision on the same lines in Ashby v Minister of Immigration [1981] 1 NZLR 222. In this case, the plaintiffs’ case was based on the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination 1965, which had been ratified by New Zealand. The plaintiffs sought a declaration that the proposed decisions by the Minister of Immigration to exercise his discretionary power under a New Zealand statute to grant temporary entry permits to members of the South African rugby team was invalid, “Because the Minister is required to exercise his discretion in a manner that is 5 7 i) the Charter of the United Nations; ii) the Charter of the Organisation of African Unity; iii) the Commonwealth; iv) the Treaty of the Economic Community of West African States; and v) any other international organisation of which Ghana is a member.” “73. The Government of Ghana shall conduct its international affairs in consonance with the accepted principles of public international law and diplomacy in a manner consistent with the national interest of Ghana”. Neither of these two constitutional principles is to be interpreted as altering the dualist stance of Ghanaian law do not authorize the courts to enforce treaty provisions that change rights and obligations in the municipal law of Ghana without legislative backing. If the law were otherwise, it would give the Executive an opportunity to bypass Parliament in changing the rights and obligations of citizens and residents of Ghana. A recent International Court of Justice case illustrates the fact that a State’s judiciary may attract for it responsibility under international law which the Executive cannot avert by itself, except by praying in aid the legislative function vested, obviously, in the Legislature. That case isJurisdictional Immunities (Germany v Italy: Greece Intervening). (3 February 2012. General List No. 143). This case arises from atrocities committed by German forces during the Second World War. The German occupation forces in Italy massacred civilians and deported large numbers of civilians to be used in forced labor victims of these atrocities having failed, after the war, to secure reparation in respect of them, the Italian courts in a series of decisions 7 8 asserted jurisdiction over claims relating to these atrocities brought against the German Government, in spite of that Government’s claim of sovereign immunity. Consequently, Germany, in December 2008, filed a suit at the International Court of Justice seeking to assert its claim of sovereign immunity against the claims before the Italian courts. Greece intervened in the case on the side of Italy, because of similar acts by German troops on its territory. The Court in its judgment delivered on 3 rd February 2012 (icj-cij/docket/files/143/16883.pdf) held that Italy was obliged, by means of its own choosing, to render void the decisions of its courts that had infringed the sovereign immunity due to Germany. It rejected various ingenious arguments by Italy to establish exceptions to the state immunity doctrine and upheld the fundamental principle of the jurisdictional immunity of States. It held that Italy, having violated this principle, must “by enacting appropriate legislation, or by resorting to other methods of its choosing, ensure that the decisions of the courts and those of other judicial authorities” that infringed Germany’s rights were nullified.(See p. 51, para 139 of the judgment). The point to be adverted to here is that the ICJ did not purport to render the decisions of the Italian courts void directly, but rather imposed an obligation on the Italian State to choose its own means of rendering void the decisions of its courts which were in breach of international law on the issue in question. Subsequent to the ICJ decision, the Italian legislature has taken action showingits willingness to act to implement the decision of the Court. This is a precedent which the Government of Ghana needs to note. Where the actions of national courts attract delictual or contractual responsibility for a State on the international law plane, the most effective remedial measure will usually be the enactment of legislation. Without prejudice to the merits of this present application, this approach is urged on the Government of Ghana in relation to its obligations under the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention. Having clarified the law relating to the obligation of this court with respect to the orders of the international tribunal established under UNCLOS, most of whose provisions have not been incorporated into Ghanaian law by appropriate legislation, we can now move on to a more plausible ground argued by the Attorney-General. It should be mentioned, though, that some 8 10 The facts the Attorney-General deposed to were as follows: there had been diplomatic correspondence between the Republic of Ghana and the Republic of Argentina (the 2 nd Interested Party) that had led to Ghana granting the 2nd Interested Party’s request for its warship, the ARA Fragata Libertad, to dock at TemaHarbour. The warship was on a diplomatic mission of promoting friendship between Argentina and other States. However, when docking at Tema, the warship was arrested and detained by the security services of the Republic of Ghana in enforcement of the orders of the High Court granted by Adjei-Frimpong J. in a suit filed by the 1st Interested Party against the 2nd Interested Party. The 2nd Interested Party applied to the High Court to set aside its order detaining the warship, but it was dismissed in a ruling delivered on 11 th October 2012. In his ruling, Adjei-Frimpong J. recounted the background events that had resulted in the suit before him. He indicated that sometime in October 1994, the 2nd Interested Party herein, had entered into a Fiscal Agency Agreement (“FAA”) with the Bankers Trust Company, a New York banking corporation. Under this FAA, the 2nd Interested Party had issued securities for purchase by the public. The 1 st Interested Party herein had purchased two series of bonds issued by the 2 nd Interested Party. When the 2nd Interested Party defaulted on the bonds, the 1st Interested Party sued it and obtained judgment in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. The 2nd Interested Party failed to settle the judgment debt. On 15 th May 2005, the 1st Interested Party commenced action against the 2 nd Interested Party in the English High Court on the debt obligation adjudged by the New York court. The 2nd Interested Party raised an objection to the jurisdiction of the English High Court on the ground of state immunity. This issue went before the English Supreme Court which held that the 2nd Interested Party did not enjoy state immunity in relation to the suit and that the English court had jurisdiction to entertain the suit. The 2 nd Interested Party subsequently submitted to judgment and a consent order was made against it in favour of the 1 st Interested Party. In spite of this, the 2nd Interested Party had not paid the judgment debt. 10 11 When the 2nd Interested Party’s vessel, ARA Libertad, entered TemaHarbour on or about 1 st October 2012, the 1st Interested Party, with the leave of the High Court (Commercial Division),Accra,issued a writ against it, claiming: a. The sum of US $ 284,184,632 being the amount of the judgment awarded by the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. b. Interest on the sum of US $ 284,184,632 at the rate of 4% per annum (compounded annually) and amounting to US $ 91,784,681 as at October 1 st 2012 c. Continuing interest at the rate of 4% per annum (compounded annually) currently amounting to US$49,071 per day from 1 st October 2012 until judgment or sooner payment or d. Alternatively, interest on the amount at the prevailing commercial bank rate from 18 th December 2006 to date of final payment. After filing the writ, the 1st Interested Party applied ex parte for an order of interlocutory injunction restraining the movement of the ARA Libertad and its interim preservation. This order was granted and it was under its authority that the 2 nd Interested Party’s vessel was restrained. It was this order that the 1st Interested Party applied to the High Court to set aside. Adjei-Frimpong J. refused to set aside his earlier order. The pivotal provision of the FAA (in evidence before this Court as Exhibit A-G 6 attached to the affidavit of the Attorney-General in support of his motion) on which the ruling of Adjei-Frimpong J hinged was the following (contained in both bonds): “The Republic has in the Fiscal Agency Agreement irrevocably submitted to the jurisdiction of any New York State or Federal Court sitting in the borough of Manhattan, the City of New York and the Courts of the Republic of Argentine (“the specified Courts”) over any suit, action or proceeding against it or its properties assets or revenues with respect to the securities of this series or the fiscal Agency Agreement (a “Related Proceeding”) except with respect to any actions brought under the United States Federal security laws. The Republic has in the fiscal Agency Agreement waived any objection to the Related proceedings in such courts whether on the grounds of venue, 11 13 I find the logic in the argument sound just as I did when the court was invited to assume jurisdiction over this matter….”. Order 8, rule 3, subrule 1(m) states as follows: “Cases where leave may be granted 3(1) Service out of the jurisdiction of notice of a writ may be effected with leave of the Court in the following cases … (m) if the action begun by the writ is in respect of a contract which contains a term to the effect that the Court shall have jurisdiction to hear and determine any action in respect of the contract.” The learned trial judge did not doubt the 1st Interested Party’s status as a sovereign State entitled to immunity from the court’s jurisdiction. But he also acknowledged the universally recognized right of sovereign States to waive immunity. For him, therefore, the crucial issue was whether the 1st Interested Party had waived its immunity under the FAA. He stated his view on this issue in the following terms: “Nation states’ historical enjoyment of absolute immunity from adjudication by foreign courts has given way to the common law restrictive immunity approach whereby a claim to state immunity would not be upheld in disputes arising out of transactions entered into between states and entities which were of commercial or private law nature. Various states have varied legal regimes on the restrictive immunity approach. E. The U. has the State Immunity Act 1978 whilst the US has the Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act of 1976. It is also universally recognized that states may irrevocably waive immunity by express contract. 13 14 PHILIP R. WOOD in his work LAW AND PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL FINANCE (1995) at page 88-89 writes on principles of waiver clauses as follows: “It appears to be universally recognized in most industrialized states that a state may irrevocably waive immunity by express contract in advance and there is some support for the principle that a waiver from jurisdiction is not a waiver from enforcement”. I agree with this view. So has the Defendant/Applicant waived its sovereign immunity to the jurisdiction of this court? Reading and re-reading the wavier provision in the Fiscal Agency Agreement and the bonds which I have already cited, my understanding is that not only did the Defendant/ Applicant waive its sovereign immunity to the specified courts”, but it did’ so to the “other courts” of which in the opinion of this court once again it is one. Aside my understanding of the provision, the record before me shows that the prime issue before the U. Supreme Court when the case travelled there was whether the Defendant/Applicant has waived its immunity to the jurisdiction of the U High Court which to my understanding was one of the “other courts.” In the decision of the U Supreme Court which is now reported in the [2011] 4 ALL ER 1191, holding 3 of the headnote reads: “The bonds contained a submission to the jurisdiction of the English Court; Argentina had unambiguously agreed that a final judgment on the bonds in New York should be enforceable against Argentina in other courts in which it might be amenable to a suit on the judgment…” Adjei-Frimpong J. then goes on to quote with approval the following passage from Lord Phillips P.S. in that case (at pp 1210-1211): “If a state waives immunity it does no more than place itself on the same footing as any other person. A waiver of immunity does not cover jurisdiction where, in the case of 14 16 the principle of res judicata for the purpose of proceedings properly brought in a Ghanaian court in which issues determined in a foreign court arise. Subsequent to the 2nd Interested Party’s failure to persuade the High Court to set aside its orders, it brought action against Ghana before the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea, alleging that Ghana had breached international law by detaining its warship and requesting the release of the ship, among other reliefs. Pending the determination of this substantive suit, the 2nd Interested Party filed an application before the Tribunal for provisional measures against Ghana. On 15th December 2012, the Tribunal gave its ruling on the application for provisional measures, in which it ordered Ghana to release the detained ship unconditionally and immediately and to ensure that it was resupplied to enable the ship to sail out of Ghana’s maritime areas. It was after this order by the Tribunal that the learned Attorney-General filed, as earlier indicated, on 19th December, 2012 the present motion on notice for orders of certiorari and prohibition against the High Court. Finally, judicial notice is taken of the fact that during the pendency of these proceedings the ARA Fragata Libertad, the Argentinian warship, sailed away from Ghana in breach of the High Court orders without resistance from the Ghanaian authorities. The Law In the affidavit sworn to by the learned Attorney-General to support his motion, the principal ground that he appears to urge in support of this application is that in his paragraph 14, which is in the following terms: “That a true and proper construction of the above provision of the FAA neither confers jurisdiction on the Court in respect of the substantive Suit nor confers jurisdiction on it in respect of subjecting the warship to civil proceedings commenced in any Court within the Republic of Ghana.” 16 17 He is, of course, referring to the waiver provision in the bonds, which has been quoted above. In the light of the view of Adjei-Frimpong J that the doctrine of res judicataapplies in relation to the interpretation put by the English Supreme Court on the waiver clause, it would be worth this Court’s while to explore the extent to which res judicata applies to the interpretation of the waiver clause and is therefore conclusive of this issue in this case. In other words, to what extent is the interpretation is to be put on the waiver clause an open issue before this Court? There is case law in England which has decided that a foreign judgment entitled to recognition in England may give rise to res judicata, either in the sense of a cause of action estoppel, which precludes a party to proceedings from asserting or denying the existence of a cause of action whose existence or non-existence has been pronounced on by a foreign court, or in the sense of an issue estoppel, which prevents a matter of fact or law necessarily decided by a foreign court from being re-litigated in England. Regarding issue estoppel, which is what is relevant on the facts of this case, the House of Lords held by a majority in Carl Zeiss Stiftung v Rayner& Keeler Ltd. (No. 2) [1967] 1 A. 853, 917, 925, 967 that a foreign judgment can give rise to issue estoppel. Lords Reid, Hodson, Upjohn and Wilberforce expressed the view in this case that issue estoppel can be based on a foreign judgment, although in such a case the doctrine should be applied with caution because of the uncertainties flowing from differences in procedure in foreign jurisdictions. Lord Wilberforce made the following illuminating remarks in his judgment (at p. 967): “As a matter of principle (and we are really thrown back upon principle), whether the recognition of vested rights, or upon considerations of public interest in limiting relitigation, there seems to be no acceptable reason why the recognition of foreign judgments should not extend to the recognition of issue decisions. From the nature of things (and here it is right to recall Lord Brougham’s warning) this, in the case of foreign judgments, may involve difficulties and necessitate caution. The right to ascertain the precise issue decided, by examination of the court’s judgment, of the pleadings and possibly of the evidence, may well, in the case of courts whose procedure, decisionmaking technique, and substantive law is not the same as ours, make it difficult or 17 19 Court had no jurisdiction to try the claim of the claimant. Another High Court judge refused to set aside the order of his brother and dismissed the application. On appeal to the Court of Appeal, the appeal was allowed, with the Court declaring that the High Court did not have jurisdiction to entertain proceedings against Argentina for recognition and enforcement of the judgment obtained in New York. With leave of the Supreme Court, the claimant appealed to that Court. The issues that the Supreme Court had to decide were: first, whether the proceedings before them were “proceedings relating … a commercial transaction” within the meaning of section 3 of the State Immunity Act 1978; second, whether Argentina was prevented from claiming state immunity in respect of the proceedings by section 31 of the Civil Jurisdiction and Judgments Act 1982; third, whether the bonds contained a submission to the jurisdiction of the English court in respect of the proceedings before the Supreme Court within the meaning of section 2 of the State Immunity Act 1978; fourth, whether the claimant was entitled to raise at the inter partes hearing two new points that it had not relied on in its earlier ex parte application; the final issue was whether, having regard to the answers to the issues already outlined above, Argentina was entitled to claim state immunity in respect of the claimant’s claim. The third of the above issues is the relevant one with respect to issue estoppel on the interpretation of the waiver clause in the FAA it was cast in terms of submission to jurisdiction within a particular statutory framework, in substance the issue to be decided was whether Argentina had effectively waived its state immunity through the language contained in the waiver clause. However, to put the answer to the third issue in context, I will set out the answers of the English Supreme Court to some of the other issues as well. The Supreme Court held that proceedings “relating to … a commercial transaction” within the meaning of section 3 of the State Immunity Act 1978 did not extend to proceedings for the enforcement of a foreign judgment which itself related to a commercial transaction and therefore the English proceedings were not proceedings relating to a commercial transaction. Accordingly, Argentina was not excluded from state immunity by virtue of section 3. The appeal was allowed on the 19 20 second issue, the Court holding that section 31(1) of the Civil Jurisdiction and Judgments Act 1982 was not an additional barrier to be overcome before enforcing a foreign judgment against a state, but was an alternative scheme for restricting state immunity in the case of foreign judgments and that its effect was that a foreign judgment against a foreign state would be recognized and enforceable in England if the normal conditions for recognition and enforcement of judgments were fulfilled and theforeign state would not have been entitled to state immunity if the foreign proceedings had been brought in the United Kingdom. On the third issue, of particular interest to this Court, the English Supreme Court held that on a true construction, the relevant provisions of the bonds constituted both an agreement to waive immunity and an express agreement that the New York judgment could be sued on in any country which would have jurisdiction, but for state immunity. It held further that England was such a country. Accordingly, Argentina had submitted to the English jurisdiction by a prior written agreement for the purposes of section 2 of the State Immunity Act 1978. Accordingly, Argentina was not entitled to claim state immunity in respect of the proceedings brought by the claimant. The decisions of the Court on the fourth and fifth issues, which related to procedure, will not be gone into here. It is clear that, although the proceedings in England were at a preliminary stage in the sense that the action was an application to set aside an order giving leave to the claimant to serve Argentina out of jurisdiction, the construction of the provisions of the bonds relating to waiver of immunity by Argentina was on the merits. We are thus willing to accept as res judicata the interpretation put by the English Supreme Court on the contested waiver clause quoted supra. The issue attracting the estoppel is that relating to whether the language of the waiver clause was to be interpreted to mean that the Republic of Argentina had waived its sovereign immunity and subjected itself to the jurisdiction of “other courts.” As indicated earlier, Adjei-Frimpong J. quoted with approval the words of Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers, PSC, by which he affirmed that Argentina had waived its immunity through the 20

Republic V HIGH Court (COM. DIV.), Accra,NML EX Parte Attorney- General (Autosaved)

Course: Constitutional law of Ghana and its history (FLAW306)

University: University of Ghana

- Discover more from:

Recommended for you

Students also viewed

- Judgment PS Investment V Ceredec & ORS-1

- Standard BANK Offshore Trust COMP. LT. VRS National Investment BANK & 2 ORS

- An Analysis of the Kelson S Theory of La

- Peter Ankumah V. CITY Investment CO. LTD

- Yakubu Awbego Vrs. Tindana Agongo Akubayela ; Immovable property – Allodial title to land, ownership of land, traditional evidence, resolution of conflicts arising from traditional evidence

- Attorney-General v Guardian Newspapers Ltd (No 2)