- Information

- AI Chat

THE Concept OF Criminal LAW

Constitutional law of Ghana and its history (FLAW306)

University of Ghana

Preview text

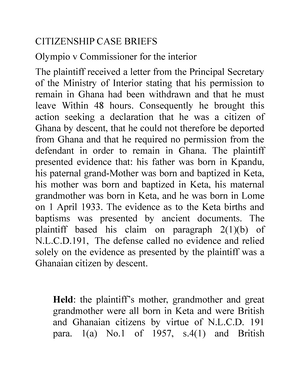

CRIMINAL LAW

What is Criminal Law?

It can generally be described as the branch of public law dealing with the substantive aspect of crimes. Criminal law basically is an attempt to dissect crime. In effect, it is the study of crime.

What is crime?

Just like other legal concepts, the definition of ‘crime’ poses some problems.

Blackstone defines crime as;

“An act committed or omitted in violation of a public law, forbidding or commanding it.”

This definition is also handicapped. In classifying law, one can have two main groups, namely; public law and private law. Under public law are constitutional law and criminal law. Private law includes tort and contract. If Blackstone’s definition is accepted, then it would mean that every violation of a provision of constitutional law would also be a crime. This is not true. For example, Article 296 of the 1992 Constitution require that any person or authority exercising discretionary power has a duty to be candid and fair. Such a person is required not to act in a manner that is capricious, arbitrary or biased either by resentment, prejudice or personal dislike. If a person exercising authority ignores this provision, it wouldn’t amount to a crime.

Halsbury’s Laws of England defines crime thus:

“A crime is an unlawful act or default which is an offence against the public, and renders the person guilty of the act of default liable to legal punishment. While a crime is often also an injury to a private person who has a remedy in a civil action, it is an act or default contrary to the order, peace and well-being of society that a crime is punishable by the state.”

The Criminal Offences Act, 1960 (Act 29), the word ‘crime’ and ‘offence’ are used interchangeably. Therefore, when we say that a person has committed an offence, we mean that he has committed a crime. Section 1 of Act 29 reads;

“Offence has the same meaning as crime”

Crime has also been defined by the same Section 1 as;

“any act punishable by death or imprisonment or fine”

This definition raises problems. In the first place it means that one has to always weigh whether a particular conduct would fall into any of the stipulated modes of punishment above before ascribing the tag of a ‘crime’ to it. Secondly there are minor offences which are punished by other modes of punishment like executing a bond to be of good behavior or just by caution.

1 | P a g e

The Canadian Supreme court in the case of Proprietary Articles Trade Association vrs A for Canada (1931) AC 310 gives us three properties of a crime. These are;

- Prohibited act : A crime is an act which is prohibited by law. If one violates this prohibitory act, there are sanctions in the form of punishment for it. Let’s illustrate it with the offence of stealing in Ghana. Section 124(1) of the Criminal Offences Act (29) reads;

“Whoever steals shall be guilty of a second degree felony.”

Section 97 of Act 29 reads:

“Whoever commits rape shall be guilty of a first degree felony and shall be liable on conviction to imprisonment for a term not less than five years and not more than twenty-five years”.

2**. Statutory Prohibition:** The act which is being sought to be prohibited should something which has been clearly spelt out at the time a person is said to have violated it. If a driver is charged with the crime of “unauthorized stopping” today, it means that as at today, there must have been in place a statute that one can point to as forbidding “unauthorized stopping”. On the other hand, if the driver is charged with the crime of “unauthorized stopping”, while in reality the law prohibiting that conduct would come into effect tomorrow, then the driver has not committed any crime today. This is because as at today, there is no statute prohibiting that conduct.

The importance of the need for a statutory prohibition is well grounded as one of the key pillars of what is known as the “General Principles of Legality.” In Criminal law, the “principle of legality” is sometimes used to mean, “the ideal of the rule of law.” There are several principles which underpin criminal law. The State is imbued with the power to punish offenders who flout the law. There are however legal parameters within which the state can punish. One of the principles of legality is known as “ nullum crimen, nulla poena sine lege praevia lege poenali – shortened to nullum crimen, nulla poena sine lege’ ’

This is a Latin expression meaning that ‘no offence is deemed to have been committed unless the law prohibits that act and the punishment for it has been sanctioned in a written law.’

This maxim can be split into two, namely;

a. Nulla poena sine praevia lege

b. Nulla poena sine lege scripta

(a) Nulla poena sine praevia lege

This simply means that a conduct or an act or omission can be deemed to be unlawful only when at the time of the commission of the act, there was a positive law that prohibits the conduct.

This principle is given a constitutional backing in Article 19(5) of the 1992 constitution;

2 | P a g e

contempt of itself notwithstanding that the act or omission constituting the contempt is not defined in a written law and the penalty is not so prescribed.”

Article 126(2) of 1992 Constitution reads;

“(2) The Superior Courts shall be superior courts of record and shall have the power to commit for contempt to themselves and all such powers as were vested in a court of record immediately before the coming into force of this Constitution.”

Section 10 of Act 29 reads;

“Saving for contempt of court

This Act does not affect the power of a Court to punish a person for contempt of Court.”

3. Punishment: the breach of a statute must carry with it a punishment. This is what is known as ‘penal consequences’. It is believed that it is the fear of punishment which generally deters people from breaching that statute. Although there some persons who even without the ‘punishment’ element would still obey a statute, majority may be tempted to disobey it if there are no corresponding sanctions in place for a breach. It is believed that without the punishment aspect to a crime, the prohibitions become just a moral code, just like the 10 Commandments in the Bible. As one writer puts it;

“Thus without the individual’s fear of the criminal sanction, criminal laws would only be a set of moral exhortations which would be obeyed at the will and determination of the individual.”

In the case of Proprietary Articles Trade Association v A for Canada (1931) AC 310, the court stated;

“Criminal law connotes only the quality of such acts or omissions as are prohibited under the appropriate penal provisions by authority of the State. The criminal quality of an act cannot be discerned by intuition nor can it be discovered by reference to any standard but one: is the act prohibited with penal consequences? ....... the domain of criminal jurisprudence can only be ascertained by examining what acts at any particular period are declared by the State to be crimes, and the only common nature they will be found to possess is that they are prohibited by the State and that those who commit them are punished”.

The procedure adopted following an act may by itself give an indication of whether it is a crime or not. Where an act by a person would result in the institution of criminal proceedings against the person, in that he could be arrested, investigated, and charged, with the consequences of being punished, then it would be a crime.

Other Features of Crime:

a. It carry with the general condemnation of the community.

4 | P a g e

b. Criminal law operates by means of commands, directives, what to do and what not to do at any given time

c. These commands, directives are binding on all that falls within that scope. There is therefore uniformity of enforcement. It is only the State and the institutions it has established that has the capacity to apply uniform standards for similar crimes in sentencing.

d. Crimes are not only harmful to the victim but constitute a threat to the entire society as whole.

The concept of over breadth and vagueness

Related to the principle of legality is the concept of over breadth and vagueness. All persons are entitled to be informed as to what the law commands or forbids. In other words, the law should tell us with reasonable clarity what it expects of us. This means that the law should be reasonably precise, predictable and certain. A statute is vague and overboard where it either forbids or requires the doing of an act in terms so vague that men of common intelligence must necessarily guess at its meaning and differ as to its application. This concept was also up consideration in the Tsikata v Republic.

The concept requires that the statute must provide an ascertainable standard of guilt. The statute creating the offence must use language which will convey to the average mind information as to the act or omission which is intended to be criminalized. Justice Douglas remarked in the US case of Papachristou v City of Jacksonville that failing to give a person of ordinary intelligence fair notice that his contemplated conduct is forbidden by statute is unconstitutional.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CRIME AND MORALITY

In the olden times, there was virtually no distinction drawn between crime and morality. This was due to the fact that societies were very simple and the nature of crimes were restricted to just a few. What was termed a crime were what most people in the society would generally condemn as morally reprehensible. Acts like murder, rape, robbery and treason were frowned upon vehemently as highly immoral. Their criminalization therefore was not seen as out of place.

However, as society became more complex and the population grew, more sophisticated acts of humans necessitated that out of expediency, laws be put in place to check them. It was not because their acts were immoral. There are still a lot of human actions that although they may be regarded as immoral, are not crimes. Examples are adultery and fornication, which are not criminalized in many countries. Societies differ, therefore the issue of what is immoral in a society may not be so in another society. Examples are prostitution and homosexuality.

The reason why many immoral acts are criminal is because of the belief that they are a threat to the survival and good of the society itself. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the belief was that there were certain wrongs which were forbidden by a law’ which no human authority would tolerate, even if they wanted to do so. Crimes like murder, rape, robbery and treason are typical examples. They were regarded by society as so palpably wrong to the public good that they ought to be criminalized. In other words, a breach should attract sanctions as they are wrongs in themselves.

5 | P a g e

29). The case for the prosecution was that the first appellant had an affair with both his mother- in-law and his sister-in-law (the other appellants). They pleaded guilty to the charge and were convicted and sentenced to prison terms and a fine respectively.

On their appeal against their conviction and sentence, counsel for the appellants contended that having an affair with a mother-in-law or a sister-in-law did not constitute an offence. Accordingly, the magistrate should not have accepted the plea of guilty. Counsel for the Republic however supported the conviction on the grounds that the chief and elders of the appellants’ village and others had warned the appellants to desist from their immoral acts and association but they had not paid any heed to the warnings, and that if members of the family of the women had not exercised restraint, serious breach of the peace would have been caused. The court found on the evidence that the first appellant had lived peacefully with the three women for over seventeen years and had had two children with each of them.

The court allowed the appeal and held that under the provisions of section 207 of the Criminal Code, 1960 (Act 29) the offence of conduct conducive to the breach of the peace could only be committed at a public meeting or in a public place. But in the instant case, the acts of the appellants complained of were committed away from the public’s eye. Therefore, notwithstanding the fact that customary law frowned upon such conduct, it was not caught by Act 29. Furthermore, since on the evidence the first appellant had lived peacefully and cohabited with the three spouses for over seventeen years, if opposition from the family was now feared, then it was the family which should be restrained.

AIMS AND FUNCTIONS OF CRIMINAL LAW

1. Standard behavior : Through acts of prohibition, human acts that are frowned upon by society on the pain of punishment help to regulate and maintain an acceptable behavior. As people do not generally like to be punished, they are more likely to behave well. In the absence of criminal law, societies would be akin to a ‘state of nature’.

2. Organization: Without criminal law, society would be thrown into disarray. Through criminal law, structures of societies are kept intact. People are better able to live a predictable lifestyle. Institutions and individuals get to know their limits of freedom. This is because they have a fair warning in advance of an act that would be deemed an offence. This helps to avoid criminalizing acts that are without fault.

Moreover, crimes are such that they are very unsafe to allow individuals to seek redress on their own. The State through its structures ensure that persons who are wronged are able to get redress in a more civilized way.

3. Protection of the weak: Flowing from the discussions so far, it can be seen that one of the greatest beneficiaries of criminal law is the weak and vulnerable in society. Criminal law ensures that stronger and more powerful persons do not take advantage of the weaker ones. Offences like robbery, rape and murder usually show ‘powerful’ individuals taking advantage of the weaker ones.

7 | P a g e

4. Protection of properties: Individuals and groups are in a better position to work and acquire properties within a sound environment. Criminal law ensures that owners of properties are better protected, while frowning upon illegal modes for the acquisition of properties.

5 of the State: Criminal law contributes to the survival and protection of the state and its institutions. In Part IV of Act 29 can be found a list of offences against the safety of the state. These offences include “treason” and “unlawful training”. Offences against the peace of the state like” riot”, “rioting with weapons”, “carrying offensive weapons” are all meant to protect not only individuals, but also the state itself.

6 of International Order: Certain acts of human conduct are regarded as so abominable that they threaten the international order. They are regarded as very serious and offending international law. Examples of such offences are “crimes against humanity”, “war crimes”, “genocide”, and “torture” and “piracy”. Criminal law ensures that such offences are punished by all nations under the principle of universal jurisdiction, irrespective of where they were committed or the nationality of the offender.

7 between serious and minor offences: Even when certain human acts are prohibited and criminalized, there is the need to differentiate between a major offence and a minor offence. Criminal law ensures that even when people fall short of acceptable human behavior, punishments must be reasonable and commensurate with the offence. Criminal law thus helps to create some amount of fairness in how people are punished.

CLASSIFICATION OF OFFENCES

Offences in Ghana can be classified under five (5) main headings, namely;

1 punishable by death

2, First and Second degree felonies

Misdemeanors

Offences punishable by Fines

Offences triable Summarily and on Indictment

1. Offences punishable by Death:

Offences which attract the death penalty are restricted to very few crimes which are regarded as very serious and so should equally attract the highest form of punishment. These are high treason, treason, murder and genocide. These are covered by the 1992 constitution of Ghana, Suppression of Robbery Act, 1972(NRCD 11) and the Criminal Offences Act, 1960(Act 29).

Article 3(3) of the constitution which governs high treason reads;

“(3) Any person who (a) by himself or in concert with others by any violent or other unlawful means, suspends or overthrows or abrogates this Constitution or

8 | P a g e

First and second degree felonies cannot be settled by the parties. The law enjoins that they be investigated and the accused sent to court.

3. Misdemeanors:

These are offences that are not regarded as serious as the felonies. Such offences attract a punishment which should not exceed imprisonment for more than 3 years. An example of such offence is “Assault”. This does not mean that the punishment is mandatorily a term of imprisonment. Other lesser modes of punishment like fines, executing a bond to be of good behavior and a caution are all acceptable. Misdemeanors are offences amenable to a settlement.

4. Offences punishable by fines:

Fines refer to a sum of money which a convict is required to pay as a punishment. The use of only fines as a mode of punishment for convicts, is usually reserved for minor offences like motor traffic and sanitation offences. In the event of failure/refusal to pay the fine however, the convict is required to spend a term of imprisonment. It must be noted that sometimes fine is imposed in addition to a term of imprisonment.

5. Offences triable Summarily and on Indictment:

Offences can also be classified according to their mode of trial. Where it is trial on indictment, committal proceedings take place at the District Court before the accused is tried at the High Court, with a jury or assessors. This is in respect of serious offences like Murder, Manslaughter, Treason, Rape.

The nature of the offence would determine whether it should be summarily or on indictment. In some cases, the law also gives a discretion to the Attorney General to also determine the nature of the trial.

Section 2(1)(2) of Act 30 reads;

“2. Mode of trial (1) An offence shall be tried summarily if

(a) the enactment creating the offence provides that it is punishable on summary conviction, and does not provide for any other mode of trial; or

(b) the enactment creating the offence does not make a provision for the mode of trial and the maximum penalty for the offence on first conviction is a term of imprisonment not exceeding six months, whether with or without a fine.

(2) An offence shall be tried on indictment if

10 | P a g e

(a) it is punishable by death or it is an offence declared by an enactment to be a first degree felony; or

(b) the enactment creating the offence provides that the mode of trial is on indictment.”

READING MATERIALS

1 Tsikata v Republic [2003-2004] SCGLR, 1068 @1086-1092)

Glah v Rep [1992] 2GLR 15

Debrah v THE REPUBLIC [1991] 2GLR 517

Articles 19(5), 19 (11), 19(12) of the 1992 Constitution

Hassan v. The State [1962] 2 GLR 150

H.J. N Mensah Bonsu: The General Part of Criminal Law- The Ghanaian Casebook, pages 1-87.

Smith and Hogan’s CRIMINAL LAW 14TH ED. Pages 1-.

TUTORIAL QUESTIONS

The arguments of the Appellant and the decision of the Supreme Court in Tsikata v The Republic [2003-2005] 2GLR 294 are just reflections of the maxims, “nulla poene sine pravia lege” and “Nulla pena sine lege scripta” under the general principles of legality in Criminal Law. Discuss.

Explain the various ways in which offences can be classified in Ghana.

Discuss the aims and functions of criminal law. What do you think are some of the reasons hampering the realization of these aims and functions?

“A crime may be a sin, but a sin may not be a crime.” How true is this statement considering the relationship between morality and crime?

What are victimless crimes? Should they be decriminalized?

(G. AYISI ADDO)

11 | P a g e

THE Concept OF Criminal LAW

Course: Constitutional law of Ghana and its history (FLAW306)

University: University of Ghana

- Discover more from: